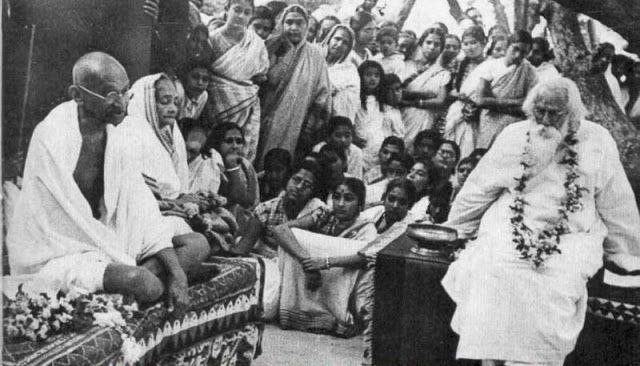

Rabindranath Tagore, mystic, painter and Nobel laureate for literature is among the leading personalities of Modern India. He was awarded the Nobel prize in Literature for his collection of well known poems Gitanjali.

Rabindranath Tagore, mystic, painter and Nobel laureate for literature is among the leading personalities of Modern India. He was awarded the Nobel prize in Literature for his collection of well known poems Gitanjali.

Rabindranath Tagore

Bangali Poet and Visionary

Early Years

Born in Calcutta on May 7, 1861, Rabindranath was the youngest of fourteen children. His father, Debendranath Tagore, was a Sanskrit scholar and a leading member of the Brahmo Samaj. Rabindranath’s early education was imparted at home. In school, while others use to learn their lessons, he would slip into more exciting world of dreams. Inspired by his older nephew, he wrote his first poem when he was hardly seven. At the age of seventeen, his first book of poems was published. In 1878, he went to England for further studies in Law, but returned back in just seventeen months as he did not find the studies interesting.

The young Tagore devoted most of his time to writing poems, plays, short stories and novels. In 1883, he got married to Mrinalini Devi. He taught his wife Bengali and Sanskrit. In this period of his life Tagore published a series of works, many based on the traditional village society of contemporary Bengal. In 1891, he went to Shileida and Sayadpur to manage his father’s estates. Living among the rural poor, he became acutely sensitive to their hardships. Many of the Tagore’s themes centre around village life, introduction of ‘western’ elements, and their natural surroundings. His 1912 collection Galpa Guccha is based completely on rural Bengal. His other notable works in this period include Sonar tari, Kalpana and Chitra.

For all of his love of the country, Tagore was averse to violence and the politics of assassination. He did not mind saying so openly, for which he was much misunderstood. He became deeply aware of the sources of Indian culture and creativity. Out of this came his ‘Vision of Indian History’. Yet Tagore was beginning to look beyond the national horizon and the urgencies of politics. In his play ‘Prayaschitto’, (Atonement), he presented a singing sadhu with the message of love. It was viewed as more poetical than practical. Tagore’s mind was turning more and more universal; in a letter he wrote, “We must go beyond all narrow bounds and look towards the day when Buddha, Christ, and Mohammed become one”. The idea of the universal man (viswamanava) was slowly taking shape in his mind.

Visit to England

This all suddenly changed in 1912. He then returned to England for the first time since his failed attempt at law school as a young man. In 1912, he was aged 51, and accompanied by his son. On the long voyage to England he began translating, for the first time, his latest selections of poems, Gitanjali, into English. At once, the Christian West came in touch with the seeds of daily immortality as Tagore hinted at reincarnation, eternity, infinity, the open and shut rhythm of a bird flying across the sea. The veil of immortality is shown to be so close to the dreary Victorian London that other English poets inhabited:

endless, such is thy pleasure.

This frail vessel thou

emptiest again and again,

and fillest it ever with fresh

life.

This little flute of a reed

thou hast carried over hills

and dales, and hast breathed

through it melodies eternally

new.

At the immortal touch of

thy hands my little heart loses its limits in joy and

gives birth to utterance ineffable.

Thy infinite gifts come to me only on these very

small hands of mine. Ages pass, and still thou

pourest, and still there is room to fill.

When thou commandest me to sing it seems that

my heart would break with pride; and I look to thy

face, and tears come to my eyes.

All that is harsh and dissonant in my life melts

into one sweet harmony–and my adoration spreads

wings like a glad bird on its flight across the sea.

Tagore hints at the magnificent journey from the smallest of the small to the largest of the large, at the end of which Man utters the divine I AM of the Old Testament, the movement from koham to deham to Aham, I AM. Only divine grace earned after births in countless wombs and wandering the blind alleyways of desire and alienation from existence results in the discrimination, not this, not that, to pronounce divinity with blessed assurance:

way of it long.

I came out on the chariot of the first gleam of

light, and pursued my voyage through the

wildernesses of worlds leaving my track on many a

star and planet.

It is the most distant course that comes nearest

to thyself, and that training is the most intricate

which leads to the utter simplicity of a tune.

The traveller has to knock at every alien door to

come to his own, and one has to wander through all

the outer worlds to reach the innermost shrine at

the end.

My eyes strayed far and wide before I shut them

and said “Here art thou!”

The question and the cry “Oh, where?” melt into

tears of a thousand streams and deluge the world

with the flood of the assurance “I am!”

Almost all of Tagore’s work prior to that time had been written in his native tongue of Bengali. He decided to do this just to have something to do, with no expectation at all that his first time translation efforts would be any good. He made the handwritten translations in a little notebook he carried around with him and worked on during the long sea voyage from India. Upon arrival, his son left his father’s brief case with this notebook in the London subway. Fortunately, an honest person turned in the briefcase and it was recovered the next day. Tagore’s one friend in England, a famous artist he had met in India, Rothenstein, learned of the translation, and asked to see it. Reluctantly, with much persuasion, Tagore let him have the notebook. The painter could not believe his eyes. The poems were incredible. He called his friend, W.B. Yeats, and finally talked Yeats into looking at the hand scrawled notebook. Yeats was to write of how this work stunned him with its beauty and simplicity.

Glory of God is Man fully alive

Tagore was no bhakta devotee. He called himself “shunned at the Temple Gates”. Yet Gitanjali overflows with the human experience and longing for the Eternal lover, the divine infinite who embraces the human condition in all its brokenness, and in all its glory. Tagore’s God is both immanent and transcendent, personal yet infinite with an indelible signature written on life. Tagore takes time to simply put aside the work of the day and sit with the Lord in all his glory of nature and friendship. For Tagore, time and again, life is a song sung into the beauty of nature, the divine self communication of lives sung into existence wherever they are found. There is no life without God, for if it is, then it is toil after toil in countless wombs:

The works that I have in hand I will finish

afterwards.

Away from the sight of thy face my heart knows

no rest nor respite, and my work becomes an

endless toil in a shoreless sea of toil.

Today the summer has come at my window with

its sighs and murmurs; and the bees are plying their

minstrelsy at the court of the flowering grove.

Now it is time to sit quiet, face to face with thee,

and to sing dedication of life in this silent and

overflowing leisure.

Poets poe, and seek the graces of the Muse and worship at her shrine. Not so for Tagore, the Lord is his Master Poet, and Tagore seeks to be the devotee whom the Lord can play a sweet sound as like a flute of Lord Krishna:

master poet, I have sat down at thy feet. Only let

me make my life simple and straight, like a flute of

reed for thee to fill with music.

It seems that Tagore had little time for those who sit removed from toil and work with japa. His Lord is wholly immanent and transcendent, to be found with hand on the tiller, in the sweat of the brow, robustly embracing this creation with all its attendant labours and sacrifices. Deliverance is found in action, karma yoga, where the Lord is found:

beads! Whom dost thou worship in this lonely dark

corner of a temple with doors all shut? Open thine

eyes and see thy God is not before thee!

He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard

ground and where the pathmaker is breaking stones.

He is with them in sun and in shower, and his

garment is covered with dust. Put of thy holy mantle

and even like him come down on the dusty soil!

Deliverance? Where is this deliverance to be

found? Our master himself has joyfully taken upon

him the bonds of creation; he is bound with us all

for ever.

Come out of thy meditations and leave aside thy

flowers and incense! What harm is there if thy

clothes become tattered and stained? Meet him and

stand by him in toil and in sweat of thy brow.

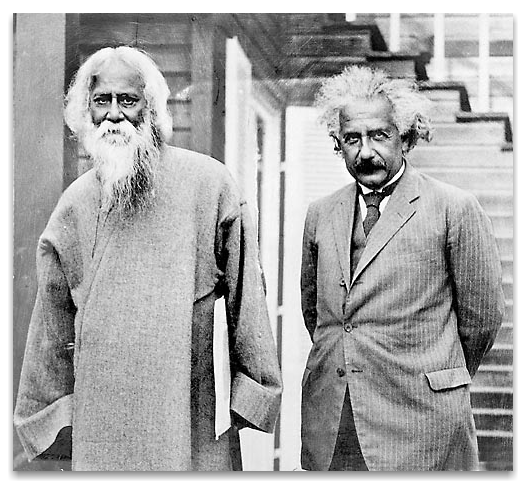

Knighthood and Honours

His spiritual presence was awesome. His words evoked great beauty. Nobody in Victorian England had ever read anything like it. The poet T.S. Eliot was yet to arrive with his shanti, shanti, shanti. A glimpse of the mysticism and sentimental beauty of Indian culture were revealed to the West for the first time. Less than a year later, in 1913, Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature. He was the first non-westerner to be so honoured. Overnight he was famous and began world lecture tours promoting inter-cultural harmony and understanding. In 1915 he was knighted by the British King George V.

Humble in the glory of the God of Nature, yes, but renunciate ascetic, not:

the embrace of freedom in a thousand bonds of

delight.

Thou ever pourest for me the fresh draught of thy

wine of various colours and fragrance, filling this

earthen vessel to the brim.

My world will light its hundred different lamps

with thy flame and place them before the altar of

thy temple.

No, I will never shut the doors of my senses. The

delights of sight and hearing and touch will bear thy

delight.

Yes, all my illusions will burn into illumination of

joy, and all my desires ripen into fruits of love.

Amristsar

But in 1919, the horror of the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre stunned Tagore and he renounced his title. In a letter to the Viceroy he wrote, “The disproportionate severity of the punishment inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the method of carrying it out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilized governments and these are the reasons which have painfully compelled me to ask your Excellency to relieve me of my title.. ” Tagore remained a true patriot, supporting the national movement and writing the lyrics of the “Jana Gana Mana“, which was adopted as India’s national anthem.

thou art the ruler of the minds of all people

Thy name rouses the hearts of Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat,

the Maratha country, Dravida, Utkala and Bengal;

It echoes in the hills of the Vindhyas and Himalayas,

it mingles in the rhapsodies of the pure waters of Yamuna and Ganga

They chant only thy name.

They seek only thy auspicious blessings.

They sing only the glory of thy victory.

The salvation of all people waits in thy hands,

O! Dispenser of India’s destiny,

thou art the ruler of the minds of all people

Victory to thee, Victory to thee, Victory to thee,

Victory, Victory, Victory, Victory to thee!

The Ego builds a prison to wall out the rest of the world, and makes itself its own God. Ego hides the true reality of man and shuns the name of God. It will be its own creator, unbeknownst to itself, hurting its true self.

this dungeon. I am ever busy building this wall all

around; and as this wall goes up into the sky day by

day I lose sight of my true being in its dark shadow.

I take pride in this great wall, and I plaster it with

dust and sand lest a least hole should be left in this

name; and for all the care I take I lose sight of my

true being.

When the Ego comes into the light of day and Truth, and the voice of conscience, it cannot deny the ground of its being, for its ground is false, false, false. Here Tagore shows that Truth is the resident in every heart, and Truth speaks to the Ego:

is this that follows me in the silent dark?

I move aside to avoid his presence but I escape

him not.

He makes the dust rise from the earth with his

swagger; he adds his loud voice to every word that I

utter.

He is my own little self, my lord, he knows no

shame; but I am ashamed to come to thy door in

his company.

“Prisoner, tell me, who was it that bound you?”

“It was my master,” said the prisoner. “I thought I

could outdo everybody in the world in wealth and

power, and I amassed in my own treasure-hose the

money due to my king. When sleep overcame me I

lay upon the bad that was for my lord, and on

waking up I found I was a prisoner in my own

treasure-house.”

“Prisoner, tell me, who was it that wrought this

unbreakable chain?”

“It was I,” said the prisoner, “who forged this

chain very carefully. I thought my invincible power

would hold the world captive leaving me in a

freedom undisturbed. Thus night and day I worked

at the chain with huge fires and cruel hard strokes.

When at last the work was done and the links were

complete and unbreakable, I found that it held me

in its grip.”

Every man has a feminine side, and courageous is the man who would admit it. Yet here, Tagore writes of his longing for the Lord as like a Gopi seeking Krishna, asking every flower, every branch, every leaf, ‘Where is my Lord?’ Reminiscent of the other songster and seeker of Krishna, Mirabai, Tagore also seeks his Lord in the dusty byways and in the forest with a heart filled with ache and longing:

all, my lover, hiding thyself in the

shadows? They push thee and pass

thee by on the dusty road, taking thee

for naught. I wait here weary hours

spreading my offerings for thee, while

passers by come and take my flowers,

one by one, and my basket is nearly empty.

The morning time is past, and the

noon. In the shad of evening me

eyes are drowsy with sleep. Men going

home glance at me and smile and fill

me with shame. I sit like a beggar

maid, drawing my skirt over my face,

and when they ask me, what it is I

want, I drop my eyes and answer them not.

Oh, how, indeed, could I tell them

that for thee I wait, and that thou hast

promised to come. How could I utter

for shame that I keep for my dowry

this poverty. Ah, I hug this pride in

the secret of my heart.

I sit on the grass and gaze upon the

sky and dream of the sudden splendour

of thy coming–all the lights ablaze,

golden pennons flying over thy car,

and they at the roadside standing

agape, when they see thee come

down from thy seat tot raise me from

the dust, and set at thy side this

ragged beggar girl a-tremble with

shame and pride, like a creeper in a summer breeze.

But time glides on and still no sound

of the wheels of thy chariot. Many a

procession passes by with noise and

shouts and glamour of glory. Is it only

thou who wouldst stand in the shadow

silent and behind them all? And only I

who would wait and weep and wear out

my heart in vain longing?

Yet for all his longing, Tagore felt an outsider with doubt. His longing is filled with an alienation, that, when rewarded, is overpowered by the prison of the ego. So the ego will think and think about its unworthiness, false humility and seek to have the answers when anugraha, (grace) is showered down:

thou didst ask. Indeed, what had I done for thee to

keep me in remembrance? But the memory that I

could give water to thee to allay thy thirst will cling

to my heart and enfold it in sweetness. The morning

hour is late, the bird sings in weary notes, neem

leaves rustle overhead and I sit and think and think.

Many years later Tagore was to reflect about his poetry. He was to write,

“When I look back and consider the long, uninterrupted period of my work as a poet, one thing appears clear to me that it was a matter over which I had hardly any authority. Whenever I wrote a poem, I thought it was I who was responsible for it, but I know well today that this was far from the truth. For in none of those small individual poems was the real purport of my whole poetical work wholly significant. What the real purport is I had no knowledge of previously. Thus, without being aware, of the Ultimate, I have continued adding one poem to another. Whatever limited idea I may have ascribed to each of them, today, with the cumulative aid of all my poems I have come to realise, surpassing each of their individual meanings, one supreme and unbroken idea had flowed steadily through them all, so that years afterwards I wrote:

you play with me in your jesting mood?

Whatever I may want to say

you do not allow me to express.

Residing in the innermost me

you snatch words from my lips

With my words you utter your own speech,

mixing your own melody.

What I wish to say I seem to forget;

I only say what you want me to say.

In the stream of songs I lose sight of the shores

drifting into a far unknown?”

Between 1916 and 1941, Tagore published 21 collections of songs and poems and held lecture tours across Europe, the Americas, China, Japan, Malaya, Indonesia etc … In 1924, he inaugurated the VISVA BHARATI UNIVERSITY at Shantiniketan, an All India Centre for culture. Tagore died in Calcutta on 7th August, 1941.

On Death and parting:

that what I have seen is unsurpassable.

I have tasted of the hidden honey of this lotus

that expands on the ocean of light, and thus am I

blessed–let this be my parting word.

In this playhouse of infinite forms I have had my

play and here have I caught sight of him that is

formless.

My whole body and my limbs have thrilled with his

touch who is beyond touch; and if the end comes

here, let it come–let this be my parting word.

This page last updated 11 November 2019

This page first updated 18 March 2001

© Saieditor.com

![]()