Following a deeply rooted passion to serve the Divine, Florence Nightingale combined a strong will and intellect with a determination to serve where it was most needed. She went to the Crimea to aid soldiers dying with war wounds and her efforts brought about long-lasting social reform, initiatives in nursing and hospital administration.

Early Years and Family

Florence Nightingale was born in Florence, Italy on 13 May 1320. She was privately educated by governesses – an education which was then taken up by her father – and had a more liberal upbringing than most women of her time. She was expected to marry well, and took up social rounds and engagements with her sisters. As early as seventeen she felt a desire to do something more productive and positive with her life. In 1837, she wrote in one of her diaries that God had called her to His service, but for what, she was unsure. This uncertainty was to torment her for the next 16 years.

In 1839, both Nightingale sisters were presented at court, and Florence met Henry Nicholson, who wooed her for the next six years until she finally rejected his marriage proposal. She could give no concrete reason other than her desire to do God’s will, whatever that was. Again, she was overwhelmed by uncertainty about what her life’s work should be, and her spells of quiet frustration and spiritual agony worried her mother. In 1842, Florence learned of the work of the Institute of Deaconesses at Kaiserwerth, Germany, regarding the training of nurses for work in hospitals. At Kaiserwerth, religious single women and widows, all from good families, worked at nurses and teachers to help the sick and mentally ill.

Her family – her mother in particular – flatly rejected Florence’s proposal to enter the Institute. Florence Nightingale was to suffer this denial both spiritually and physically, for the next six years. She believed that God had called her again, yet she was unable to follow her calling; she felt unworthy. The best she could do was to nurse sick relatives, friends and villagers. By 1847, she had worked herself into a state of ill-health, marked by migraines, chronic coughing and a near breakdown. She then went to Rome in 1848 for her health, and made her way with the help of friends to Kaiserwerth in Germany. Again, her mother flatly refused to allow her to enter the school.

Institute in Kaiswerwerth, Germany, where Florence Nightingale studied.

Florence defied her mother and entered the school and studied for two years. When she went home to England, she faced her mother’s anger. She discovered that her father, sister and grandmother were all ill, and Florence spent the next two years nursing them. Once again though the will of her mother, she was plunged into social life and suffered as she obediently followed her mother’s desires for her. Periodically, she nursed the sick under the guidance of the Sisters of Charity in Paris. Then, in 1853, Liz Herbert made a decision on Florence’s behalf; she recommended her as the new superintendent of the Institution for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in London. At 37, Florence Nightingale’s life work began in earnest.

Life’s Work

Her mother was horrified; her father stood up for her and gave her an allowance of £500 a year to live on. For the next 14 months, as Superintendent of the institution, Florence Nightingale surprised the committee that appointed her in two respects. First, the “ministering angel” they thought they had appointed proved to be a tough minded and practical administrator who relentlessly re-organised the hospital from food to medical supplies to sanitary conditions. Secondly, Florence Nightingale insisted that any poor and ill woman should be admitted, not only those who were members of the Church of England. With a fight, she got most of what she wanted. She also wanted trained nurses; however, this request was not easy to fulfil. She then began to formulate plans for a training school for nurses along the lines of what she had experienced at Kaiserwerth. Her plans were interrupted, however, when England and France declared war on Russia in 1854.

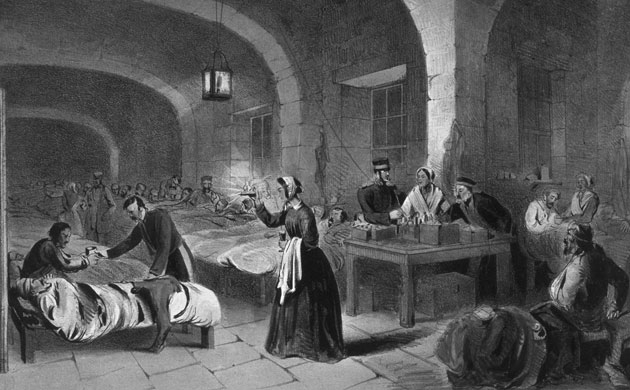

War reports in The Times stated that England and France were victorious in war. However, the casualty rate was alarmingly high. In October 1854, Florence Nightingale left England for the shores of the Black Sea with a handful of poorly trained nurses. Soon after, she was appointed Superintendent of the Female Nursing Establishment of the English General Hospitals in Turkey. When she arrived, she found the hospitals in Scutari appalling. Besides a lack of basic medical supplies (bandages, splints, stretchers), nourishing food, adequate clothing and clean water, the hospital was overrun with filth, vermin and backed-up cesspools. In addition, th wounded, the diseased and the dead were all crowded together in rooms with little or no ventilation. Foresight had prompted Florence to bring supplies with her.

Lack of supplies and unsanitary conditions were not Florence’s only problems. She met with stiff resistance from military doctors and staff in Scutari, despite holding an official position as Superintendent. Florence began her work in the face of opposition; she and her nurses washed, scrubbed, cleaned and removed dirt from the hospital. When she asked for a better Barrack Hospital and was refused, she used her own money to build a new hospital and to get the men better quarters.

Her final triumph at Crimea was when most of the doctors relented and finally allowed Florence Nightingale and her nurses to actually care for the patients and assist the doctors. Thus, ‘the bird’ as she was called, became a ‘ministering angel’ and then the ‘lady with a lamp’ and finally an administrator. The struggle was long and slow, for Florence Nightingale was battling men set in their ways, for they not only objected to a woman coming close to military matters but also stubbornly refused to admit there was any problem with the military medical system. Within a year after her arrival at Crimea, the casualty rate among injured soldiers went from 42% down to 22% per thousand men.

The Superintendent was not satisfied. Morale among the injured and invalid was very low. She wanted to do something for their emotional state as well. To the outrage of her military opponents, she set up reading and recreational rooms for the soldiers, assisted them in managing and saving money, and held classes and lessons for them. She cared for the whole person. The establishment was still outraged over the lack of segregation among the patients and nurses. In July 1856, she declared her work complete and travelled home to England, and the Queen invited her to court to receive a brooch which had a George Cross, the Royal Cipher and bounded with the words, “Blessed are the Merciful”.

Gold enamelled brooch, presented to Florence Nightingale by Queen Victoria, 1855.

Here is a letter written to Florence Nightingale by Queen Victoria.

Dear Miss Nightingale,—You are, I know, well aware of the high sense I entertain of the Christian devotion which you have displayed during this great and bloody war, and I need hardly repeat to you how warm my admiration is for your services, which are fully equal to those of my dear and brave soldiers, whose sufferings you have had the privilege of alleviating in so merciful a manner. I am, however, anxious of marking my feelings in a manner which I trust will be agreeable to you, and therefore send you with this letter a brooch, the form and emblems of which commemorate your great and blessed work, and which, I hope, you will wear as a mark of the high approbation of your Sovereign!

It will be a very great satisfaction to me, when you return at last to these shores, to make the acquaintance of one who has set so bright an example to our sex. And with every prayer for the preservation of your valuable health, believe me, always, yours sincerely,

Nursing Schools

After her struggles at Scutari and public recognition for her works, Florence Nightingale’s work was far from finished. She kept fighting for hospital reform. Diagnosed with a nervous condition and heart problem, Florence continued her work with a passion to pursue her mission. When she was ill, she read and wrote from her bed. When she was well, she visited influential people and secured support for her programs. The army hospital at Scutari was only a beginning; she now went after the Army Department itself. She wrote an 800 page report, “Notes on Matters Affecting the Heath, Efficiency, and Hospital Administration of the British Army (1858) and A Contribution to the Sanitary History of the British Army During the Late War with Russia (1859) which was submitted to the Royal Commission. Members of the Commission received the report favourably and as a result, drastic changes were made to Army medical procedures between 1859 and 1861.

By 1861, Florence had become a respected medical authority and was asked to investigate army medical conditions in India. Her reputation was spreading, and with the help of a published book Notes on Hospitals, completely revolutionised hospital construction and administration. In 1860, the Nightingale Training School for Nurses at St George’s Hospital opened and in the same year, Florence Nightingale published, Nursing – What it Is, and What it Is Not. Her health was to fail again and she was invalided to her bed where she remained for many years. However, she was not inactive from her bed, and wrote and advised many people, local and foreign, who came to her, looking for advice on hospital matters.

Having devoted her life to the physical comfort of mankind, she now turned inward to her own spiritual condition, reading everything she could. As in her early adult years when she wrestled with religious questions and callings, she returned to a state of religious and intellectual turmoil. The world went on and forgot her. In 1907, sick and confused, she became the first woman to receive the Royal Order of Merit. It was presented to her in her bedroom. From her illness, her only reply was, “Too kind, too kind”. Three years later, nearly blind, she died in her sleep on August 13, 1910.

Florence Nightingale, the lady with the lamp

Florence Nightingale has been romanticised as an angel of mercy, a quiet, meek, self-sacrificing nurse moving quietly among hospital wards with a lamp. What is not remembered is that she was a reformer, an administrator and a tireless campaigner for better medical conditions for the hospitalised, and for women. She was trying to do a job in a social environment which rejected the presence of women among men and strove for segregation of men and women in hospitals. She was not alone in her position and many others were to follow her and take up the need for change in social conditions, the need for welfare for the poor and sick, and a general change in attitude towards education and status.

![]()