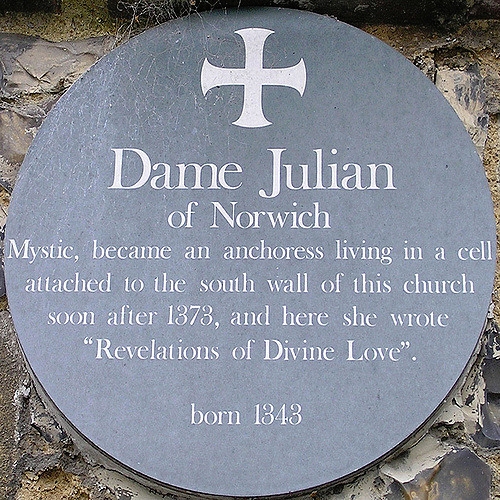

Julian was an Anchoress. It is fairly certain that she was not a nun. An anchoress was a person called to a solitary life, but one that was not cut-off from the world, but one anchored in it. Her life was one of prayer and contemplation, a life highly thought of by people of the time. Her 14th Century blockbuster The Revelations Of Divine Love made her the first woman to write a book in the English language (that we know of).

Dame Julian’s home was a small room, or cell, attached to the Church of St. Julian, just off one of the main streets of Norwich. She probably took her name Julian from the Saint of the Church. There was a ‘Rule of Life’ associated with this order drawn up in the 13th century, which stated that the cell should have 3 windows that opened; one into the Church, so she could hear Mass and receive the Blessed Sacrament; one to communicate with her servant, who would have lived close at hand; one window was to open onto the street, to give advice to those who sought it.

Through this window, she would meet with passers by who sought the advice of a holy woman. Her unusual lifestyle was understood by all as a form of consecration to God, for her entrance into this life would have been a public event. The Bishop of the town along with the crowd of the faithful held a public service in which she was sealed into her apartment, there to spend the rest of her days in prayer and service to the spiritually hungry. Traditionally, this was done by a mature woman, not by a woman in her child bearing years.

Independent Sisterhoods

In the later Middle Ages many people found an answer to their spiritual needs by becoming recluses rather than by joining the regular religious orders. This was particularly marked in East Anglia, and in Flanders, with which the town of Norwich had commercial links. From the thirteenth century to the time of the Reformation, fifty hermits and anchorites are recorded for Norwich and about thirteen for Lynn, which compared well with London, where there were about twenty. Norwich is the only English city known to have contained informal sister-hoods, or beguinages.

It was the fashion at that time in the Fourteenth century for women in the West to dedicate their lives unto God and live informally in seclusion and detachment from the world. Some were called Beguines, sometimes anchorites and others were referred to as recluses. It is a similar state to initiation into sanyas, the unfettered life.

In some respects, independent sisterhoods presented problems for the local ordinary (the Bishop) as all religious were under his charge, be they enclosed, in active work for the cure of souls, or in independent hermitages and sisterhoods. Independent women were a particular threat to male Bishops, who were not used to having their authority questioned by bright, intelligent and knowledgeable women. The subject of Beguines and independent sisters was to come up in not one but three Church Councils.

Precarious times

Julian’s times were the High Middle Ages, where devotion and mystics were flourishing in the pre-reformation church. It is also the same time that the hidden excesses and harshness of church power were beginning to foment the seeds of discord and discontent. There were quiet whisperings. It is a dangerous time, witches were being burnt at the stake, John Wycliffe was alive in England at the same time (Julian was to outlive him) and his ideas were being spread by itinerant priests who were called ‘Lollards’. If apprehended, they were sentenced to be dragged through the streets by horses for many days to discourage others. It would have been an easy matter for Julian to be tried and burnt as a dissenter. At the time when we can place Julian of Norwich at approximately seventy years of age, Archbishop Arundel was forbidding the Bible to be discussed in the English Language, more so, it was NOT to be discussed by people who were not priests and nuns. Julian lived and wrote in precarious times.

Devotion to the Passion

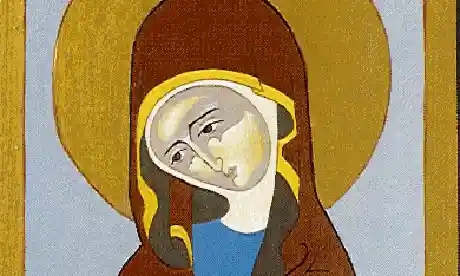

The key to understanding many elements of Julian’s writings and her time can be found in the major Christian piety of that era, which was largely Devotion to the Passion of Christ. ‘Rood‘ is a word from Anglo-Saxon, the so-called “The Dream of the Rood” (c. eighth century) being the oldest English Christian poem. Christ is depicted as the young warrior, who mounts the cross to suffer in triumph. By the twelfth century, there had taken place what J. A. W. Bennett called ‘one of the greatest revolutions of feeling that Europe has ever witnessed’ and devotion was concentrated on the agonised Saviour, the unexampled afflictions of the Crucified, his head bowed with grief, his wounds bleeding, his arms outstretched in dying love. This is evidenced throughout the Middle Ages, notably in Julian of Norwich, and continued throughout many more centuries to finally lead much more to a spirituality of the Risen Lord and, later, of the Incarnation (God becoming Man).

Historical Evidence

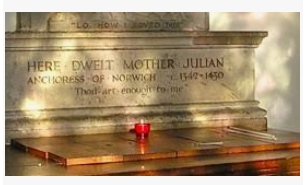

Little is known directly of the details of Julian’s life. She writes that she was living at home and was 30-and-a-half-years-of-age when the first ‘showing’ occurred for her, after suffering a severe heart attack. We hear of her first as an anchoress in 1394, and thereafter there is spasmodic evidence of her being still alive up to 1416. Julian was mentioned in four wills and bequests and also by her contemporary (and sometimes erratic mystic), Margery Kempe of Lynn.

Margery Kempe lived in nearby Lynn and came to Julian seeking help. She had given birth to fourteen children and had gone mad following each childbirth. Julian counselled Margery for many days. Margery then trudged off to Compostela, to Rome, Jerusalem, and had her erratic bouts of “holy shouting” for her Lord. She came home and dictated her book to her daughter in law, a German woman, then to a priest. It was called The Book of Margery Kempe.

Here she gives a telling of her visit to the recluse at Norwich:

“Then she was bidden by Our Lord to go to an anchoress in the same city, named Dame Jelyan, [i.e. Julian) and so she did, and showed her the grace that God put into her soul, of compunction, contrition, sweetness and devotion, compassion with holy meditation and high contemplation, and fully many holy speeches and dalliance that Our Lord spoke to her soul; and many wonderful revelations, which she showed to the anchoress to find out if there were any deceit in them, for the anchoress was expert in such things, and good counsel could give.

The anchoress, hearing the marvellous goodness of Our Lord, highly thanked God with all her heart for his visitation, counselling this creature to be obedient to the will of Our Lord God and to fulfil with all her might whatever he put into her soul, if it were not against the worship of God and profit of her fellow Christians, for if it were, then it were not the moving of a good spirit, but rather of an evil spirit. ‘The Holy Ghost moveth ne’er a thing against charity, for if he did, he would be contrary to his own self for he is all charity. Also he moveth a soul to all chasteness, for chaste livers are called the temple of the Holy Ghost, and the Holy Ghost maketh a soul stable and steadfast in the right faith, and the right belief.”

A Cross is Presented

With the Passion of Christ being the central focus of local piety, Julian lay dying in bed. She had already received the last rites. She was only thirty years old. The priest came but could no longer give her again the Sacrament. Instead he brought with him a boy carrying the Crucifix which was held up before her so she could gaze upon God, upon Jesus’ dying while she herself was dying. Julian, propped up in bed after her heart attack, refused to look. She was gazing upward to Heaven. She was to later write “me thought I was well, for my eyes were set upright into Heaven”. She finally consented to look at the cross, probably only for the medical reason that it involved less physical strain to look stright ahead than to go on looking upwards.

Then her visions began, her “Shewings” as she was want to call them in her Middle English. She seemed to see the figure of Jesus on the Cross bleed and bleed so copiously she thought that all her bed would be filled with his blood. She saw garlands upon garlands of blood fall from his crown of thorns, like pellets, like rain drops from thatched roof eaves, like scales on a herring. She saw his flesh torn and drying like that of a man dragged through the streets for days, then as if it had been hanged upon the gallows in the cold bitter winds for days upon end, so dried and desiccated it had become, like a cloth hanging out and tattered in the wind

Then a man of religion came to me and asked how I did, and I said that during the day I had been raving. And he laughed out aloud and heartily. And I said: The cross that stood at the foot of my bed bled profusely; and when I said this, the religious I was speaking to became very serious and surprised. And at once, I was very ashamed of my imprudence, and I thought: this man takes serious every word I could say, and he says nothing in reply. And when I saw that he treated it so seriously and so respectfully, I was greatly ashamed, and wanted to make my confession…

Writings

Probably within a few years of her showings Julian wrote the first version of her book, the Short Text. She was still far from having absorbed the meaning of her revelation and in particular she still viewed herself and her readers from within a distorting perspective which she later abandoned. She appears to have thought of herself as a ‘contemplative’, and she certainly addresses herself to people ‘that desire to live contemplatively’. She seems to have a conventional enough notion of what it means to live contemplatively’. Contemplatives are people who are not ‘occupied willfully in earthly business’, and who gladly ‘nought [despise] all thing that is made, for to have the love of God that is unmade’. They seek that spiritual repose which can only be had when the soul is ‘noughted for love’. Julian’s self-image in the Short Text insists that she is not to be regarded as a ‘teacher’: “I am a woman, lewd [uneducated], feeble and frail.” This may be regarded as a typical ‘modesty formula’, wholly relevant to Julian in her times and place. We may speculate that Julian wrote like this either before or shortly after entering her cell.

And from the time it was revealed, I desired many times to know in what was our Lord’s meaning. And fifteen years after and more, I was answered in spiritual understanding, and it was said: What, do you wish to know your Lord’s meaning in this thing? Know it well, love was his meaning. Who reveals it to you? Love. What did he reveal to you? Love. Why did he reveal it to you? For love. Remain in this, and you will know more of the same. But you will never know different without end.

The revelation continued to exercise her mind, and some fifteen years after the revelation of 1373 she seems to have finished a new, much longer, version of her book, and even then she felt that she had only made a beginning. It was not until 1393 that she completed the Long Text.

In the course of the First Showing, Julian tells us,

A LITTLE THING, THE QUANTITY OF AN HAZEL NUT

In this same time our Lord shewed me a ghostly [spiritual] sight

of His homely loving.

I saw that He is to us everything that is good and comfort-

able for us: He is our clothing that for love wrappeth us,

claspeth us, and all encloseth us for tender love, that He may

never leave us; being to us all-thing that is good, as to mine

understanding.

Also in this He shewed me a little thing, the quantity of an

hazel-nut, in the palm of my hand; and it was as round as a

ball. I looked thereupon with eye of my understanding, and

thought; What may this be? And it was answered generally

thus: It is all that is made. I marvelled bow it might last,

for methought it might suddenly have fallen to naught for

little(ness). And I was answered in my understanding: It

lasteth, and ever shall (last) for that God loveth it. And so

All-thing hath the Being by the love of God.

In this Little Thing I saw three properties. The first is that

God made it, the second that God loveth it, the third that

God keepeth it. But what is to me verily the Maker, the

Keeper, and the Lover – I cannot tell; for till I am Substanti-

ally oned to Him, I may never have full rest nor very bliss:

that is to say, till I be so fastened to Him, that there is right

nought that is made betwixt my God and me.

In the Short Text her writing is focussed in one direction: since we can never have real bliss until we are ‘so fastened to (God) that there might be right nought that is made between’ God and us, it follows that we should ‘nought all thing that is made for to have the love of God that is unmade’. This moral still stands in the Long Text, but there it is complemented by a much greater emphasis on the other side of the picture: God loves all that is made, and his love is immediately at work in all of it. We must not be impressed by creatures in themselves, but equally we do not have to turn aside from them in order to meet God’s love.

Julian judged herself as ‘folly’ in raising the question “Why had God allowed sin?” It was a question which was to be resolved in her writings in an unusual way, illustrating the love of God as the love of a Father, Mother and protector. In the 59th Chapter of the long text, Julian describes the Trinity with the feminine attributes of affection, succour and nurture:

As truly as God is our Father, so truly is God our Mother, and he revealed that in everything, and especially in these sweet words where he says: I am he, that is to say, I am he, the power and goodness of fatherhood; I am he, the wisdom and the lovingness of Motherhood; I am he, the light and the grace which is all blessed love; I am he, Trinity; I am he, the unity; I am he, the great supreme goodness of every kind of thing; I am he who makes you to love; I am he who makes you to long; I am he, the endless fulfilment of all true desires. For where the soul is highest, noblest, most honourable, still it is lowest, meekest, mildest.

… From this it follows that truly as God is our Father, so truly God is our Mother. Our Father wills, Our Mother works, our good Lord the Holy Spirit confirms. And therefore it is our part to love our God in whom we have our being, reverently thanking and praising him for our creation, mightily praying to our Mother for mercy and pity and to our Lord the Holy Spirit for help and grace. For in these three is all our life: nature, mercy and grace, of which we have mildness, patience and pity …

Julian then shows that sin does not divorce man or woman from the endless ocean of divine love. God, in the role of Mother of a child, allows the child to experience pain, suffering and distress in various ways that one may negotiate life and find at the end that divine protection was always there:

… for we need to fall, and we need to see it; for if we did not fall, we should not know how feeble and wretched we are in ourselves, nor too, should we know completely the love of our Creator.

For we shall truly see in heaven without end that we have sinned grievously in this life; and notwithstanding this, we shall truly see that we were never hurt in his love, now were we ever of less value in his sight. And by the experience of this falling we hall have a great and marvellous knowledge of love in God without end; for enduring and marvellous is that love which cannot and will not be broken because of offences…

The mother may sometimes suffer the child to fall and to be distressed in various ways, for its own benefit, but she can never suffer any kind of peril to come to her child, because of her love … the sweet gracious hands of our Mother are ready and diligent about us, for he in all his work exercises the true office of a kind nurse, who has nothing else to do but attend to the safety of her child. It is his office to save us, it is his glory to do it, and it is his will that we know it; for he wants us to love him sweetly and trust in him meekly and greatly. And he revealed this in these words: I protect you very safely.

A Strong Wit

The most significant development that occurred between the completion of the Short Text and the writing of the Long Text is that Julian freed herself from the ‘contemplative’ strait-jacket and came to terms with herself as an intelligent woman with a probing and insistent mind. She is still prepared to accuse herself of ‘folly’ in wondering why God did not prevent sin, but she no longer accuses herself of pride; and the foolishness for which she blames herself seems to reside more in the grumbling attitude with which she asks her question than in the question itself. And it is noticeable that this time she is much less easily satisfied by the Lord’s assurances, and pursues her questioning much further and far more rigorously.

She is still well aware that we must respect God’s ‘privities’, but she is also convinced that God intends us to seek knowledge. If something is, for the moment, meant not to be revealed to us, then God shows it to us precisely as something still ‘closed’; that is to say, we do not have to be shy of probing, because God himself shows us where the line is drawn beyond which we are not going to get any answers.

How do we live?

All of humanity exists in a ‘Christ’ through whom all things are made, and to whom, as Teilhard De Chardin wrote, all things wend toward as their end. Julian was shown that the soul emerges from God and that the soul is the spark of the Divine in whom we live, rather than seek. Like the Buddhist and the Hindu, it is a journey veiled in illusion, for we never perceive that we always existed in this loving God from our beginnings:

OUR SUBSTANCE IS IN GOD

I saw full assuredly that our Substance is in God, and also I

saw that in our sense-soul God is: for in the self-(same) point

that our Soul is made sensual, in the self-(same) point is the

City of God ordained to Him from without beginning; into

which seat He cometh, and never shall remove (from) it. For

God is never out of the soul: in which He dwelleth blissfully

without end….

And all the gifts that God may give to creatures. He hath

given to His Son Jesus for us: which gifts He, dwelling in

us, hath enclosed in Him unto the time that we be waxen

and grown – our soul with our body and our body with our

soul, either of them taking help of other -till we be brought

up unto stature, as nature worketh. And then, in the ground

of nature, with working of mercy, the Holy Ghost graciously

inspireth into us gifts leading to endless life.

And thus was my understanding led of God to see in Him

and to understand, to perceive and to know, that our soul is

made-trinity, like to the unmade blissful Trinity, known and

loved from without beginning, and in the making oned to

the Maker.

There is neither wrath nor forgiveness in God. For in all of us there is an indefectible will that leads us home to our origin, rather like a “Wholeness Navigator” that the New Age movement sometimes speaks about. There is a “godly will” that never swerves from God. This is what we really are, it is really our ‘substance’. Thus in one sense we must say, we are more truly in heaven than on earth. We have liberation and do not realise it.

Dealing with Pain

This then leads to a “gap”. The goal is God, and the journey is God. The End is God. How does she deal with sin? How does Julian of Norwich move from the sense of separation from God, the well known veil of Maya to the vision of God?

Julian would propose that we live in penance, penance being that profitable reflection on the passion and the sufferings of Christ. It is we who are not always in peace and bliss. Acceptance of the terms of this life (undeniably painful), the puzzle and the mystery of suffering and death can only be resolved in the passion of Christ. There is no separation between the pains he suffers and the pain he suffers in all his members unto the end of the world. Thus the essential penance we undertake is “mind of his passion”. This would seem to approximate the disciplined, perpetual occupation of the mind and will with recollection of the name and form of the Lord.

“Mind of the Passion” and identification with the passion are generalised to include the whole of our earthly life as such: simply by accepting the limitations of life in this world, we are sharing in the passion of Christ, and it is in learning by faith to see God at work in all of it, we learn to recognise the presence of God in Christ on the Cross.

We continually live in illusion and we do not perceive the divine substance of our life in our moment to moment existence. In her seventh Showing, Julian had a peculiar experience.

A Rapid Showing

In the seventh Showing Julian was taken through a rapid oscillation of feeling, from extreme consolation to total desolation, and the changes were so rapid that they could not be ascribed to any change in her; as she says, there was no time for her to have committed a sin between the consolation and the desolation. The purpose of this exercise was to emphasise the point that God keeps us equally secure whatever we feel like, in weal and in woe. It is precisely because we attend to our own ‘feelings’ (our own perceptions, our own subjective experience) that we make life such a misery to ourselves.

I SAW NO WRATH BUT ON MAN’S PART

Our good Lord the Holy Ghost, which is endless life dwelling

in our soul, full securely keepeth us; and worketh therein a

peace and bringeth it to ease by grace, and accordeth it to

God and maketh it pliant. And this is the mercy and the way

that our Lord continually leadeth us in as long as we be here in

this life which is changeable.

For I saw no wrath but on man’s part; and that forgiveth He

in us. For wrath is not else but a forwardness and a contrari-

ness to peace and love; and either it cometh of failing of

might, or of failing of wisdom, or of failing of goodness:

which failing is not in God, but is on our part. For we by sin

and wretchedness have in us a wretched and continuant

contrariness to peace and to love. And that shewed He full

often in His lovely Regard of Ruth and Pity. For the ground

of mercy is love, and the working of mercy is our keeping in

love. And this was shewed in such manner that I could not

have perceived on the part of mercy but as it were alone in

love; that is to say, as to my sight.

Mercy is a sweet gracious working in love, mingled with

plenteous pity: for mercy worketh in keeping us, and mercy

worketh turning to us all things to good.

The Divine and Human Filters

Julian saw no need for a hell, was shown what God thought of the Devil and laughed whilst she was actually being shown the image, and was also shown that pain, suffering and misery were of man’s creation and man’s failings. In an opaque little story, Julian saw God, and the man running to do something for God. The man did not look where he was running and fell in a ditch, doing himself a serious hurt. Worse still, God, whom he was eager to serve, and whom he could no longer see, was still looking at him with unchanging love, now tinged with pity. It is our feeling (and our reactions) that prevent us from knowing that God is loving life into us at each and every moment of our existence.

The “mercy worketh turning to us all things to good” was to her the rebuttal of everlasting burnings and everlasting hell and judgement. Julian knew that all were created from God, of the one Substance of God, and were all destined for union with God. She did not have the knowledge base or the framework for the words, but she felt strongly that all would be one with God. Simply left as a ‘showing’, Julian clearly shows us that we experience and view life through our own filters.

An Allegory of Adam

Julian is a woman of her times. She also saw this little allegory as God creating Adam, and the Passion of Christ redeemed Adam and all men from the Fall. This is in some wise how Julian set the focus for dealing with the central fact that man had to be redeemed from sin. Redemption is achieved only in the suffering and humanity of Christ. She concludes that ‘All shall be well and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.’ She is a joyous mystic, stressing the homely love of God which has been poured upon this planet and mankind from all eternity.

Christianity, the major religion of the West, has presented to many lands and nations the knowledge of the One, Formless God, who has offered his Son to the world for the redemption (saving) of man from the fruit of his sin. In the Biblical history of the Old Testament and the New Testament, this is a masculine God. When Jesus taught the “Our Father”, he taught “Our (masculine gender role name) who art in heaven”. Western civilisation has lived with a Masculine God. Julian is a courageous woman who has seen that God is both our Mother and our Father. Moreover, Christ, suffering on the Cross is our Mother, also.

Bravely, in face of a masculine and patriarchal church laden with masculine gender and art (Think of God and Adam on the roof of the Sistine Chapel. Where is Eve?) Julian presents her “Shewing” of God as Mother and Father. Christian thought evolves and the Christian experience and understanding of God’s saving action in Jesus’s life also evolves. Perhaps, one day, due Julian and her Shewings, Christianity will evolve to seeing Mother-Father God gifting Christ to the world.

A Modern Witness

Julian of Norwich is not a Saint, but she is often called Saint in this modern era. The original church at Norwich was destroyed by bombing during World War II. This has been restored as a place of prayer by the Anglican Sisters of All Hallows, Ditchingham. Her “Shewings” reach across the boundaries between creeds and communions. A Buddhist Monk, a Hindu Sadhu and a modern Zen nun might all understand her.

Dame Julian speaks of divinity being both Masculine and Feminine, that reality is interpreted through filters, we all cause our own suffering and pain, that there is no Hell, and that the world simply is, a ‘given’ or unreal. Julian is interested in the nature of the soul and its relation unto God. She is faithful and true to the teaching of the Church, and through her sharply improved wit, seeks to stay away from doctrinal difficulties that besieged her times.

In her day, popular piety and the people of the Church, both priest and penitent, were focussed on a suffering Christ being the self-revelation of God to humanity. Julian, with her crystal-clear showings, presented many different facets of the Divine Diamond, facets which illuminate the one light that enlightens the hearts and minds of all.

LOVE WAS OUR LORD’S MEANING

This book is begun by God’s gift and His grace, but it is not

yet performed, as to my sight.

For Charity pray we all; (together) with God’s working,

thanking, trusting, enjoying. For thus will our good Lord

be prayed to, as by the understanding that I took of all His

own meaning and of the sweet words where He saith full

merrily: I am the Ground of thy beseeching. For truly I saw

and understood in our Lord’s meaning that He shewed it for

that He willeth to have it known more than it is: in which

knowing He will give us grace to love Him and cleave to

Him. For He beholdeth His heavenly treasure with so great

love on earth that He willeth to give us more light and solace

in heavenly joy, in drawing to Him of our hearts, for sorrow

and darkness which we are in.

© C. Parnell

![]()