George Fox was an English Dissenter, who was a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers or Friends. The son of a Leicestershire weaver, he lived in times of social upheaval and war.

George Fox was an English Dissenter, who was a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers or Friends. The son of a Leicestershire weaver, he lived in times of social upheaval and war.

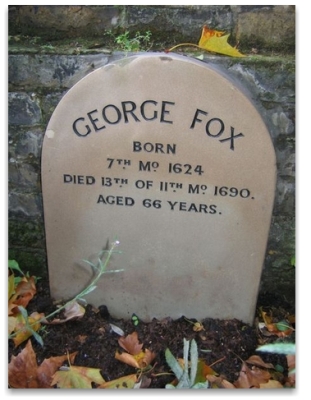

George Fox, 1624 – 1691

Founder of the Society of Friends (Quakers)

George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends (Quakers), was born at Drayton-In-The-Clay, Leicestershire, England, the son of Puritan parents. Little is known of his early life apart from what he wrote in his journal:

In my very young years I had a gravity and stayedness of mind and spirit not usual in young children: insomuch that when I saw old men behave lightly and wantonly toward each other, I had a dislike thereof raise in my heart, and I said within myself, “If ever I come to be a man, surely I shall not do so, nor be so wanton.”

Raised in the Anglican Church, George Fox was religiously inclined from his childhood, but being too poor to study theology, he was employed looking after sheep and at 19 he decided to take to the road in search of personal spiritual truth.

Fox seems to have been guided by the works of Jakob Bohme and in 1646 a sudden revelation transformed him into an impassioned preacher who burned with an inner light. He accused both Puritans and the Anglicans of holding back the advance of Christianity and was arrested 36 times in the 40 years of his mission, spending a total of 6 years in prison.

Birth of the Quakers

It began through the agency of George Fox; and the date which is generally accepted as the “birth time of Quakerism” is 1652. For some five years, Fox had been travelling round the country, spreading his message. He was understood and welcomed by some, but he also met with considerable opposition; he had been imprisoned in Derby gaol on a charge of blasphemy and had suffered considerable ill-treatment. He had been working very much on his own and he had certainly not initiated any sort of religious movement. Then, in May 1652, he was in Lancashire and had climbed to the top of Pendle Hill, near Clitheroe. It was a strange thing to do, for people did not climb hills for fun in those days, especially one well-reputed as an abode for witches; still, Fox had a habit of doing unaccountable things! The view from the summit of the far spread countryside inspired him and shortly afterwards he had a vision, or an insight, of “a great people to be gathered”. It was, in fact, the district where he would meet groups of interested people, for instance those known as the “Westmorland Seekers”.

The really significant visit which he paid, one to have far reaching and permanent effects on the history of Quakerism, was to Swarthmore Hall, near Ulverston (reached by crossing the dangerous sands of Morecambe Bay). This was a large house and property occupied by Judge Fell and his wife Margaret. Both were of a liberal outlook in religious matters and visiting preachers had already been made welcome there. Margaret Fell welcomed George Fox with great enthusiasm and was quickly “converted” to his teaching. Fell, though he never formally associated himself with the Quaker movement, was supportive and permitted meetings of Fox and his followers to take place in the Hall. Presumably because of Judge Fell’s standing in the county (and also in the nation), these group meetings were not subjected to harassment by Church and Law, which was otherwise common. Thus, for many years right up to the time of George Fox’s death, Swarthmore Hall was the “headquarters” or “powerhouse” of the Quaker movement. It was from this Hall that the early Quaker “missionaries” were sent in small groups of two or more to spread the message in different parts of the country.

Persecution and imprisonment did not prevent him from travelling throughout England, Ireland, North America and Holland, and making converts. The converts formed the Society of Friends, nicknamed Quakers after the way in which they behaved at their meetings where each individual showed his inner illumination by shudders and cries of enthusiasm and impromptu speeches.

From the Autobiography of George Fox

CHAPTER V. One Man May Shake the Country for Ten Miles (1651-1652).

… Passing on, I was moved of the Lord to go to Beverley steeple-house, which was then a place of high profession; and being very wet with rain, I went first to an inn. As soon as I came to the door, a young woman of the house came to the door, and said, “What, is it you? come in,” as if she had known me before; for the Lord’s power bowed their hearts. So I refreshed myself and went to bed; and in the morning, my clothes being still wet, I got ready, and having paid for what I had had in the inn, I went up to the steeple-house, where was a man preaching. When he had done, I was moved to speak to him, and to the people, in the mighty power of God, and to turn them to their teacher, Christ Jesus. The power of the Lord was so strong, that it struck a mighty dread amongst the people.

The mayor came and spoke a few words to me; but none of them had any power to meddle with me. So I passed away out of the town, and in the afternoon went to another steeple-house about two miles off. When the priest had done, I was moved to speak to him, and to the people very largely, showing them the way of life and truth, and the ground of election and reprobation.

The priest said he was but a child, and could not dispute with me. I told him I did not come to dispute, but to hold forth the Word of life and truth unto them, that they might all know the one Seed, to which the promise of God was given, both in the male and in the female. Here the people were very loving, and would have had me come again on a week-day, and preach among them; but I directed them to their teacher, Christ Jesus, and so passed away. The next day I went to Cranswick, to Captain Pursloe’s, who accompanied me to Justice Hotham’s. This Justice Hotham was a tender man, one that had had some experience of God’s workings in his heart. After some discourse with him of the things of God, he took me into his closet, where, sitting with me, he told me he had known that principle these ten years, and was glad that the Lord did now publish it abroad to the people.

After a while there came a priest to visit him, with whom also I had some discourse concerning the Truth. But his mouth was quickly stopped, for he was nothing but a notionist, and not in possession of what he talked of. While I was here, there came a great woman of Beverley to speak to Justice Hotham about some business; and in discourse she told him that the last Sabbath-day (as she called it) there came an angel or spirit into the church at Beverley, and spoke the wonderful things of God, to the astonishment of all that were there; and when it had done, it passed away, and they did not know whence it came, nor whither it went; but it astonished all, — priest, professors, and magistrates of the town.

This relation Justice Hotham gave me afterwards, and then I gave him an account of how I had been that day at Beverley steeple-house, and had declared truth to the priest and people there. I went to another steeple-house about three miles off, where preached a great high-priest, called a doctor, one of them whom Justice Hotham would have sent for to speak with me. I went into the steeple-house, and stayed till the priest had done. The words which he took for his text were these, “Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters; and he that hath no money, come ye, buy and eat, yea come, buy wine and milk without money and without price.” Then was I moved of the Lord God to say unto him, “Come down, thou deceiver; dost thou bid people come freely, and take of the water of life freely, and yet thou takest three hundred pounds a year of them for preaching the Scriptures to them. Mayest thou not blush for shame? Did the prophet Isaiah, and Christ do so, who spoke the words, and gave them forth freely? Did not Christ say to His ministers, whom He sent to preach, ‘Freely ye have received, freely give’?”

The priest, like a man amazed, hastened away. After he had left his flock, I had as much time as I could desire to speak to the people; and I directed them from the darkness to the Light, and to the grace of God, that would teach them, and bring them salvation; to the Spirit of God in their inward parts, which would be a free teacher unto them… The next day I came into York, where were several very tender people. Upon the First-day following, I was commanded of the Lord to go and speak to priest Bowles and his hearers in their great cathedral. Accordingly I went. When the priest had done, I told them I had something from the Lord God to speak to the priest and people. “Then say on quickly,” said a professor, for there was frost and snow, and it was very cold weather. Then I told them that this was the Word of the Lord God unto them, — that they lived in words, but God Almighty looked for fruits amongst them. As soon as the words were out of my mouth, they hurried me out, and threw me down the steps. But I got up again without hurt, and went to my lodging, and several were convinced there.

For that which arose from the weight and oppression that was upon the Spirit of God in me, would open people, strike them, and make them confess that the groans which broke forth through me did reach them, for my life was burthened with their profession without possession, and their words without fruit. [After being thus violently tumbled down the steps of the great minster, George Fox found his next few days crowded with hot discussion. Papists and Ranters and Scotch “priests” made him stand forth for the hope that was in him. The Ranters, he says, “had spent their portions, and not living in that which they spake of, were now become dry. They had some kind of meetings, but they took tobacco and drank ale in their meetings and were grown light and loose.” After the narrative of an attempt to push him over the cliffs the account continues.]

From 1650 to 1689 more than 3000 of Fox’s disciples were imprisoned, some being tortured and others dying in prison. Nevertheless, by the time of Fox’s death, there were still 50,000 ‘Friends’. Many of them emigrated to North America where the Quaker William Penn (1644-1718) founded Pennsylvania in 1682, with its capital Philadelphia, the city of ‘Fraternal Love’. He gave the new state a remarkable constitution which was the inspiration for the constitution of the United States. Today, there are nearly 300,000 Quakers of which 250,000 live in America and only 18,000 live in the UK.

The Quakers

Most faith groups have specific beliefs that their membership is expected to follow. Sometimes, as in the case of the Roman Catholic church, these requirements are numerous. The Religious Society of Friends is near the opposite end of the religious spectrum. They rely heavily upon spiritual searching by individual members, individual congregations and meetings. Some Quaker meetings at the liberal and evangelical ends of the spectrum differ significantly

The Quakers reject all dogma, creed, sacrament and hierarchy. They believe firmly that within each individual the Bible is as a ‘seed’ or a ‘divine light’ which must be uncovered through meditation. The same Spirit which inspired the the disposal of all those who know how to hear it. Supreme authority in both administrative and religious matters is associated with the ‘meetings’ where the spirit is present; decisions must be unanimous. The Quakers, like all the followers of radical reform questioned the existing social and religious order, which in part explains the persecution they suffered. But they have always distinguished themselves through their humanitarian efforts. They fought the institution of slavery , helped the victims of the two world wars and today campaign for third world countries, human rights and the position of women in society.

Quaker peace work continued after the end of the wars, taking on different forms as different needs developed. An immediate opportunity came in Germany and Austria, where large student populations were seen to be suffering severe deprivation. Food relief was undertaken through both British and American Quakers. This relief, known as “Quaker-Speisung” in Germany, made a lasting impression on the people. Later on, in the days of the Hitler regime, there were a number of Germans now in positions of responsibility who had benefited from this help and had remembered it. There were occasions when Quakers were enabled to give help to those suffering in Germany when others could not.

Simplicity, pacifism, and inner revelation are long standing Quaker beliefs. Their religion does not consist of accepting specific beliefs or of engaging in certain practices; it involves each person’s direct experience of God. There is a strong mystical component to Quaker belief. One visitor to a meeting wrote, “In Meeting for Worship, God is there … God is probably always there, but in Meeting, I am able to slow down enough to see God. The Light becomes tangible for me, a blanket of love, a hope made living.” They do not have a specific creed; however, many of the coordinating groups have created statements of faith. The statement by the largest Quaker body, the Friends United Meeting includes the beliefs in:

- true religion as a personal encounter with God, rather than ritual and ceremony

- individual worth before God

- worship as an act of seeking

- the virtues of moral purity, integrity, honesty, simplicity and humility

- Christian love and goodness

- concern for the suffering and unfortunate

- continuing revelation through the Holy Spirit

Many Quakers do not regard the Bible as the only source of belief and conduct. They rely upon their Inner Light to resolve what they perceive as the Bible’s many contradictions. They also feel free to take advantage of scientific and philosophical findings from other sources. Individual Quakers hold diverse views concerning life after death. Few believe in the eternal punishment of individuals in a Hell. All aspects of life are sacramental; they do not differentiate between the secular and the religious. No one day or one place or one activity is any more spiritual than any other.

This page last updated 29 September 2019

This page first updated 4 May 2002

©Saieditor.com

![]()