Baháʼu’lláh was a Persian religious leader, and the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, which advocates universal peace and unity among all races, nations, and religions.

Baháʼu’lláh was a Persian religious leader, and the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, which advocates universal peace and unity among all races, nations, and religions.

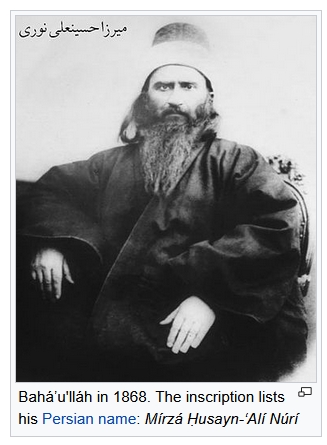

One of the Bab’s followers, Mirza Husayn-‘Ali-i-Nuri (1817-1892), announced that he was the Manifestation predicted by the Bab. He assumed the title Baha’u’llah (“glory of God”). His teachings on world peace, democracy, civil rights, equal rights for women, the acceptance of scientific discoveries, etc. were decades ahead of his time.

Bahá’ís believe in a single God who has repeatedly sent prophets into the world through whom he has revealed the “Word of God.” Prophets include Adam, Krishna, Buddha, Yeshua of Nazareth (Jesus), Mohammed, The Bab and Baha’u’llah.

The Bahá’í faith is still looked upon by many Muslims as a breakaway sect of Islam. Bahá’ís are very heavily persecuted in some countries, particularly Iran.

Bahá’u’lláh

Early life

Bahá’u’lláh – which means the glory of God in Arabic – was born Mirza Husayn Ali in 1817 into one of Persia’s most noble and privileged families. In his early life he had a relatively limited education (which was normal for the class from which he came). He learned horsemanship (he was known as a fine horseman), swordsmanship, poetry and calligraphy (he was also renowned as an excellent poet and calligrapher). His Islamic education was strictly non-technical, but despite this, his knowledge of Islam (and of other religions) was far beyond what could have been expected of someone from the wealthy governing class.

This is important because Bahá’u’lláh used his limited education to reinforce his claim to divine revelation. He argued that since he had not spent years studying the Qur’an and Arabic, how else could he be able to write as he did in Arabic? And there is no evidence to suggest that he devised his writings through his own intellectual thoughts. In 1844, just 3 months after the Báb’s declaration, Mulla Husayn carried a scroll of the Báb’s to Bahá’u’lláh. On reading it, Bahá’u’lláh recognised the claims of the Báb and at the age of 27 became his follower.

From then on, although they never met, Bahá’u’lláh and the Báb were in constant correspondence and when the Báb knew that he would soon die, he sent his pens, seals and papers to Bahá’u’lláh. It was at Bahá’u’lláh’s explicit instructions that the remains of the Báb were removed from Tabriz to Tihran and hidden in a place of safety.

Imprisonment

Two years after the Báb’s death, Bahá’u’lláh was imprisoned in Tihran, accused of taking part in the attempted assassination of the Shah of Persia. He was put in stocks and, for three days, given neither food nor water. Other Bábis were imprisoned with him and as they sat in chains, Bahá’u’lláh taught them to chant prayers which were heard by the Shah.

The reasons for Bahá’u’lláh’s arrest were not straightforward and included:

- his stature and influence as the leading member of the Bábi community

- the jealousy of the Grand Vizier

- the hatred of the Shah’s mother, who levelled unjust accusations at Bahá’u’lláh

Bahá’u’lláh’s own actions also contributed to his arrest:

- he ignored advice to keep himself hidden

- he went of his own volition to army headquarters to be arrested

Bahá’u’lláh was jailed underground in a prison with a very significant name: the Siyáh-Chál, or Black Pit. It had previously been a reservoir for the public bath.

While in prison, Bahá’u’lláh had a vision of the ‘Most Great Spirit’ in the form of a heavenly maiden who assured him of his divine mission and promised divine assistance. Bahá’u’lláh himself wrote that he had the feeling of something glowing from the crown of his head and of hearing words of protection and victory.

This is as significant for the Bahá’í revelation as the visitation of Gabriel which caused Muhammad such consternation, or the vision of God that caused Moses to swoon. This event is regarded by Bahá’ís as marking the birth of the Bahá’í revelation. It stands at the heart of Bahá’u’lláh’s claim to be the Manifestation of God.

Survival

The Bábis were often tortured and killed but the authorities were reluctant to kill Bahá’u’lláh. This was partly because of his family’s influential social position, and partly because of a personal intervention by Prince Dolgorukov, a Russian ambassador. But the main reason was that the would-be assassin of the Shah had already confessed to the crime and completely exonerated the Bábi leaders of any involvement.

The prime minister of Persia decided that it was preferable for Bahá’u’lláh to be banished from the state and he was released from prison in 1853. He was stripped of his wealth and possessions and travelled to Baghdad with his wife.

Bahá’u’lláh and his family arrived in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1853 where he stayed for 10 years. On arrival, he met followers of the Báb and his influence grew to the extent that it caused dissension, conflict and jealousy amongst the followers of the Báb. His own brother Azal, for example, grew jealous of him and proclaimed himself as the Messenger of God.

To escape the conflict, Bahá’u’lláh left Baghdad and spent the next 2 years living as a hermit in Kurdistan. His family eventually begged him to return to the city, which he did in 1856. In Baghdad, he found the Bábi community had become dispirited and divided. It seemed that his brother had not provided effective leadership, so Bahá’u’lláh spent the next 7 years teaching the basic teachings of the Báb by both word and example.

Bahá’u’lláh wrote 3 important books in Baghdad:

- Hidden Words

- Kitab-I-Iquan (Book of Certitude) (1862)

- The Seven Valleys

In them, he emphasised the importance of the spiritual paths and outlined the religious goals of the spiritual life. The Seven Valleys was a mystical work, written in response to questions from the Sufi mystics whom he met during his period as a hermit. He also set out religious doctrines, the concept of the Manifestations of God and the fulfilment of prophecy.

He continued to experience visions from the Maid of Heaven and was soon recognised as the pre-eminent Bábi leader. Eventually, the teachings and influence of Bahá’u’lláh reached the Muslim leaders of Baghdad and caused such concern that they called for his banishment. In 1863, the Governor of Baghdad reluctantly gave way to these requests and told Bahá’u’lláh that he had to leave the city.

Bahá’u’lláh proclaims his mission

In Adrianople, where he stayed from 1863-1868, Bahá’u’lláh began to reveal himself to his followers and to religious and civic leaders as the one promised by the Báb and, in so doing, formally established his mission. The Bábi community became the Bahá’í community, and their focus centred on the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh. There was conflict within his family, and Baha’u’llah was exiled to Akka. Bahá’u’lláh arrived in Akka in August 1868, so fulfilling prophecies made by Muhammad, and by Jewish prophets, about the importance of the city. He was banned from associating either with others of his party, or with the inhabitants of the city. When pilgrims arrived to see him, they would stand for hours in the hope of glimpsing him from his prison window.

At this time, Bahá’u’lláh wrote to the monarchs of Europe, including Napoleon III, the Czar of Russia, Francis-Joseph of Austria and Pope Pius IX, to proclaim his mission. Queen Victoria is alleged to have replied “If this is of God, it will endure. If not, no harm can come of it.” It was during this period that the Bahá’í greeting Allah-u-Abha (God is All-Glorious) came into use. In time, the townspeople and officials of the town began to recognise and be drawn to Bahá’u’lláh’s wisdom and spirituality – as had happened in Baghdad, Constantinople and Adrianople – and gradually, the terms of his imprisonment were relaxed.

In 1877, following the overthrow of the Sultan Abdulaziz, Bahá’u’lláh could leave the city and he moved to nearby Mazraih and later that year to Bahji. Apart from visits to Mount Carmel, he spent the rest of his life at Bahji and died there in 1892.

Successor

Bahá’u’lláh’s eldest son, Abdu’l-Bahá, was appointed his successor. He was recognised as the first to believe in Bahá’u’lláh’s mission, and the only authoritative interpreter of Bahá’í teachings.

Photographs and imagery

There are two known photographs of Baháʼu’lláh, both taken at the same occasion in 1868 while he was in Adrianople (present-day Edirne). The one where he looks at the camera was taken for passport purposes and is reproduced in William Miller’s book on the Baháʼí Faith. Copies of both pictures are at the Baháʼí World Centre, and one is on display in the International Archives building, where the Baháʼís view it as part of an organized pilgrimage. Outside of this experience Baháʼís prefer not to view his photos in public, or even to display any of them in their private homes, and Baháʼí institution strongly suggests to use an image of Baháʼu’lláh’s burial shrine instead.

Baháʼu’lláh’s image is not in itself offensive to Baháʼís. However, Baháʼís are expected to treat the image of any Manifestation of God with extreme reverence. According to this practice, they avoid depictions of Jesus or of Muhammad, and refrain from portraying any of them in plays and drama. Copies of the photographs are displayed on highly significant occasions, such as six conferences held in October 1967 commemorating the hundredth anniversary of Baháʼu’lláh’s writing of the Suriy-i-Mulúk (Tablet to the Kings), which Shoghi Effendi describes as “the most momentous Tablet revealed by Baháʼu’lláh”. After a meeting in Adrianople, the Hands of the Cause travelled to the conferences, “each bearing the precious trust of a photograph of the Blessed Beauty (Baháʼu’lláh), which it will be the privilege of those attending the Conferences to view”.

The official Baháʼí position on displaying the photograph of Baháʼu’lláh is:

There is no objection that the believers look at the picture of Baháʼu’lláh, but they should do so with the utmost reverence, and should also not allow that it be exposed openly to the public, even in their private homes. (From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi to an individual believer, 6 December 1939)

![]()