This novel opens with the startling perspective that Falco and partner are auditing businessmen whose trade is slaughter. Of wild animals and humans. Their stock in trade was measured as units of mass murder. We’ll take a look at this and its impact on the humanity of Falco and Helena Justina.

Meanwhile, Emperor Vespasian is confused that there are no monies in the imperial treasury. (An unfavourable balance of trade was the culprit.) In order to beef up the imperial statutory reserves Vespasian engages Falco and Partner to set matters aright with the Great Census of Rome.

AD 73. The Emperor Vespasian occupies the Imperial Palace in Rome. Prior to Vespasian’s accession was the mad year of four emperors in Rome. Vitellius had bankrupted the treasury by holding three feasts a day (according to Suetonius). Debts were quickly accrued and money-lenders started to demand repayment. Vitellius showed his violent nature by ordering the torture and execution of those who dared to make such demands. Such was the economy Vespasian inherited. The treasury was in ruin and the Empire had no public monies.

Four years into his term Vespasian has decided to replenish the treasury and restore the economy; the great Census of AD73 was conceived. He and his sons were the Censors, aided by the imperial staff. Falco and Helena Justina gifted the Palatine Household with sack-loads of the Imperial Purple. This leads to Falco and Partner being offered the task of auditing in the grey economy of Rome – tracking down dodgy tax declarations by the beastiarii, the slaughterers, the gladiators and the lanistae, the suppliers of the gladiators and animals who provide the executions, spectacles, and entertainment for the Roman masses.

Immediately he enters his task of auditing his first client (one Calliopus) Falco is invited to view a corpse – that of a lion, Leonidas. Informer to the core, Falco begins investigating. During his investigation, Calliopus’s main competitor Saturninus has a leopard loosed in the City. Shortly thereafter, Calliopus finds his corn supply poisoned, and his prize ostrich dies. Rumex, (a gladiator with the greatest renown in Rome) (there was plenty of graffiti about him) is found dead in bed. All grist to Falco’s mill as he continues to investigate.

When Vespasian’s men entered Rome and battled to take possession of Rome, the most important Temple on the Capitol Hill, the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (adjacent the Palatine Hill, home of Emperors) was burned down. Vespasian was undertaking reconstruction; there would also be the Forum Vespasianus, and the Ampitheatrum Flavium, the great amphitheatre which would house the Games. Thus, the venatio and trainers of beasts were vying with an eye to be the suppliers of entertainment in the new Amphitheatre. Greed is always a significant motivator of human action.

Surprise, surprise. The investigation is shelved, as there was nothing to follow up. Unable to solve who had killed Rumex, Falco and Partner returned to their commission for the Censors.

We were not men who became obsessed. I, Marcus Didius Falco, was an ex-army scout and an informer of eight years standing, a professional. Even my partner, who was an idiot, could recognise a dead end. We felt frustrated, but we handled it. After all, we had our fortunes to earn. That always helps maintain a rational attitude.

The audits continue, the demands for tax are presented, and the auditees roll over and pay up, defeated.

The Cammillus family (through the earlier work of Falco in Baetica) host Claudia Ruffina, intended betrothed of the elder son Aelianus. Previously, the younger son Justinus had eloped with Claudia to North Africa. The young Justinus is now in quest for a wild pipe dream, establishing a business around the fabled wild-garlic, silphium.

Falco and family travel to North Africa. There is a professional interest as Famia is looking to purchase more steeds for the Greens (participants in the Games). They follow the trail of Justinus and Claudia, and meet with them in Berenice. Falco discovers that Calliopus, Saturninus and Hanno are headed to Lepcis Magna for Games.

Falco’s is retained by a wild woman, Scilla, who believes one of these lanista is responsible for the dead lion who mauled her intended partner and ex-praetor, Pomponius Urtica. The denouement occurs in the Amphitheatre of Lepcis Magna where Scilla has forsworn her engagement of Falco and taken matters into her own hands. Scilla loses her life, and Falco’s Partner survives to audit for another day.

Falco and the Business of Slaughter

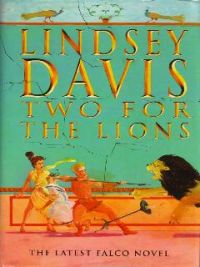

Two for the Lions opens with Falco and Partner conducting an audit of the affairs of a lanista, nearby the circus. Lanistae supply gladiators and animals, entertainment and slaughter to the masses at the Games. Also, lanistae can supply trained lions, that is, lions trained to kill; being thrown to the lions was a form of state execution in the Roman Empire.

For the lanista, success was measured satisfying the crowd in straight-forward terms of volume (of slaughter). The stock in trade of lanista and venatio was devising ever more sophisticated ways of delivering blood. Lanista and Venatio are simply suppliers and trainers, men of commerce. How has the commerce of slaughter and Games come to be?

We need to look to the history of Roman Games. When a General was victorious in field, when a man took office as aedile, or sought to curry favour in regard to being elected, then one afforded the oi poloi the spectacle of Games which consisted of combat, punishment, blood-lust and entertainment. It was called an electoral bribe of immense proportions and expenditure.

These were full scale games. At the inaugural games for the Flavium Amphitheatre, “animals both tame and wild were slain to the number of nine thousand”. Such events were occasionally on an even larger scale; Trajan is said to have celebrated his victories in Dacia in 107AD with contests involving 11,000 animals and 10,000 gladiators over the course of 123 days”. Roman games were elaborate affairs sometimes lasting many, many days.

The games were probably driven by lust, and blood-lust at that. Lust itself is destructive and inimical to true humanness. Lust is desire, a fire that can never be quenched. Blood-lust is desire to see blood spilled. This energy can spread out to become energy of crowd, or mob-violence, and have the mobs totally taken over and rioting for spilling more blood. So the formless thought-field of blood-lust simply settled over the games arena feeding on the desire to see blood spilled until there are no sources of slaughter left to spill blood with.

Lust itself is one of the six enemies of man. These are desire, anger, jealousy, greed, attachment, pride and malice. Lust today is often portrayed as lust for money, lust for sexual fulfilment and for possessions. Desire can be overpowering, and take over the mind. However, with desire, it is often attachment to the object of desire that both takes over the mind, and consumes energy. The modern equivalent of blood-lust might be violent computer games, paint-ball, and other killing-type simulations.

When blood is spilled, and the taste of blood is taken in by the mind, the mind normalises the experience and appetites can quickly change. Such was the situation in ancient Roman games. There was cruelty in punishment and execution, particularly with crucifixion and torching crucifixes. The value of human life in the slave classes and lower was often reduced … any human qualities were discarded and the person reduced to a transitional object. Once reduced to an object, the human person no longer exists. Thus, the business of slaughter comes about, reduction of humans to the animal level, little more than beasts of burden and objects of entertainment. They were made to fight animals, and to fight like animals against other humans. Cruelty often featured in fighting.

Animals were chained together and made to fight. For example, for the opening of the Flavium Amphitheatre, elephants fought bulls. Combat was put on with humans fighting animals, and gladiators fighting gladiators. The Games included formal punishment; trained lions were supplied to attack and tear apart naked prisoners tied to the stake. In a previous activity as a delator,(informer) Falco has apprehended and caused to be sentenced unto death one slave by name of Thurius, who deliberately inflicted prolonged pain and suffering upon his lady victims. Falco is anxious to see Thurius thrown to the lions in order to see justice occur and violent crime punished. This was not the case with Falco’s brother in law, Famia, who was executed using the same method in the Amphitheatre of Lepcis for Blasphemy against the Punic Gods.

Falco and Helena Justina discuss crime and punishment during the dinner with the lanista Saturninus and his wife Euphrasia. Saturninus observes that “there is justice in extinguishing life by the swipe of a lion’s paw or with the sword, and is usually fairly quick and efficient. It is neutral, dispassionate, and routine”. Helena Justina points out that “it occurs within the medium of an event called the Roman Games”, and regarded as part of the entertainment. Helena Justina’s observations are right; punishments were part and parcel of a much larger entertainment spectacle.

Falco’s Rome could well be thought of as a cruel place with little or no respect for the innate value of human life. Some classes of human life were treated with little more regard than had for animals. Pre-Christian Rome, slave owners had unrestricted sexual access to their slaves, and if an owner beat a slave to death, then whilst it was frowned upon, it was the right of the owner and none could interfere.

Was Falco’s Rome decadent? Do we conclude that Falco and Helena Justina attend the games for displays of skill and ignore the bloodlust? Saturninus calls himself a businessman who satisfies demand for a price; that is how he stays in business. Euphrasia points to Falco and Helena Justina and asserts they have disagreements about cruelty and humanity. Falco, interestingly, defines his values: HE wants to see criminals tracked down and receive their just punishment. When challenged how he defines humanity, Falco replies: kindness, Restraint, Education, a civilised attitude towards all people. Even slaves and lanistae.

Watching criminals being torn apart by trained lions gives Falco no pleasure whatsoever, and does not detract from his humanity. His humanity is also defined by his integrity in his relationships and the quality of love in his life.

Available on Amazon

Imago Roma

Lion Statuary…

![]()