Whether it is a lucky bracelet or a hamsa keychain amulet, superstitions believed to bring good fortune or ward off the bad are almost universal. They are the inspirations for a provocative new art exhibition: Magical Thinking: Superstitions and Other Persistent Notions, accessible virtually and at the Dr. Bernard Heller Museum at Hebrew Union College in New York through January 15, 2023.

Black cats, wishbones, and mirrors are among the symbols chosen for exploration by over 50 contemporary artists. Jewish (and North African/Middle Eastern) amulets such as the hamsa, an outstretched hand to ward of the “evil eye,” are among the most popular motifs. The striking works include oils, watercolors, acrylics, paper cuts, and photographs.

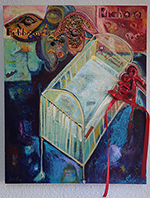

Several artists explored the use of red ribbons or string to ward off the evil eye in Jewish settings, such as tying a red ribbon on a newborn’s crib, string bracelets given out at the Western Wall in Jerusalem today, and bracelets worn by celebrities who are taken with Jewish Kabbalah teachings.

Characters from Jewish folklore, like the golem and the dybbuk, are also featured. In legend, the golem is a mythical figure molded from clay and brought to life to aid its creator, while the dybbuk is a phantom creation, often a revenge figure that interferes with the real world.

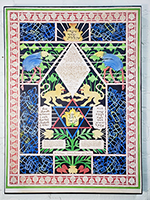

Mark Podwal created Jewish Magic, Zodiac in acrylic and colored pencil to depict various literary images about magic found in the Torah, in synagogues, and in amulets. Among these are yads, the letters of the Hebrew alphabet inscribed on a hamsa, the Lion of Judah, and most beautifully, Jerusalem rising from a rose.

Debra Lynne Amerling’s Bubbe Meises includes several superstitions about childbirth that she learned from her parents: protective red ribbons tied on the crib, “pooh pooh” (words uttered to ward off evil), and a guardian angel inscribed with the phrase “bubbe meises,” which translates roughly as “old wives’ tales.”

David Wander’s title, Mizrach (which means “east” in Hebrew), symbolizes a wall hanging that indicates which wall to face when facing Jerusalem in prayer, as is Jewish custom. This striking work, using acrylics, plaster and gold leaf on wood, features a prominent hamsa above a pillar of fire and a pillar of smoke leading to the golden Promised Land in the center. The decorative background pattern and hearts add to the appeal of this work.

Jeffrey Schrier offers another version of the hamsa, Rosh Hashanah Hamsa, combining its defense against trouble with symbols of the new year, including the shofar and a honeycomb brimming with hoped-for sweetness for the new year.

Paul Pretzer’s Renaissance-inspired oil painting on wood, The White Mouse, is a charming rendition of a superstition about scholarship. It is based on a Talmudic list of actions that induce forgetfulness and hinder learning, which includes eating from food that has been nibbled by a mouse.

Ruth Schreiber’s bronze and glass sculpture, Against the Evil Eye, refers to a superstition among some Jews that talking about wealth, good luck, or their greatest treasures – their children – can only be mentioned without bring bad luck if one can also say in Hebrew b’li ayin hara or in Yiddish, kein ayin hara, meaning “without an evil eye.”

Deborah Ugoretz is a master of papercutting. In 19th-century Eastern Europe and the Middle East, papercut amulets were believed to protect a mother and her newborn from Lilith, a Jewish mythical figure who might snatch the infant. Instead, in this contemporary work, Amulet – in Praise of Lilith, the artist is celebrating the admirable women in the Bible and the accomplishments of contemporary women artists and activists who are named in medallions around the work. She includes the name of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in Hebrew, calling on her to protect us from anti-democratic factions.

Bonnie Heller’s Kaparot: Swing for Life is one of several works picturing the kaparot atonement ritual that takes place on the eve of Yom Kippur. It consists of waving a live chicken or rooster above one’s head while reciting specific verses in the mahzor, transferring one’s sins to the bird. The unlucky fowl is then killed and given to those without access to food. Today, money in a bag is often substituted for the chicken and the money is donated to those who have been denied access to resources. Kaparot is based on the ceremony of the scapegoat as described in Leviticus 16:21-22.

Joyce Ellen Weinstein recalls an ancient Jewish folk tale in her linoleum block print on rice paper, Solomon Ibn Gabirols’ Female Golem. In one story, an 11th century rabbi was credited with bringing to life a female golem to perform household chores, a need many modern homemakers can surely appreciate. During the Middle Ages, many legends arose of wise men who created such creatures. In some stories, the golem rebelled and caused trouble, requiring it to be reduced once again to clay. Perhaps this was the seed for the story of Frankenstein.

is the title page illustration for The Dybbuk, a book by Barbara Rogasky, telling the ancient story of the daughter of a wealthy man who falls in love with a poor, orphaned scholar. The girl’s father insists she marry a rich man, causing the scholar to die of a broken heart. His ghost appears as a dybbuk (often characterized by a ghost or disembodied human spirit) on the wedding day to possess the bride, who dies to join her lover.

These and the many other works in the exhibition illuminate how magical thinking is embedded in Jewish heritage and in universal culture. Through the creativity of contemporary artists, we can explore how superstitions and the psychological need to believe in good luck and protect against evil remain a powerful factor in the human condition.

Source

Image Source

Images reproduced with permission from Reform Judaism

![]()