Galileo Galilei was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath, from Pisa. Galileo has been called the “father of observational astronomy”, the “father of modern physics”, the “father of the scientific method”, and the “father of modern science”.

Galileo Galilei was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath, from Pisa. Galileo has been called the “father of observational astronomy”, the “father of modern physics”, the “father of the scientific method”, and the “father of modern science”.

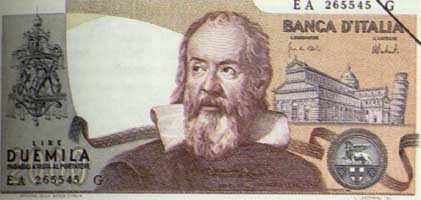

Galileo Galilei, 1564 – 1642

A Loyal Scientist

Born: February 15, 1564; Pisa, Republic of Florence

Died: January 8, 1642; Arcetri, Republic of Florence

Galileo, Icon and Scientist

Galileo is a symbol of the starting point of scientific enquiry – the expansion of Natural Science with the telescope and the break of science with the Church of the West. He was a martyr of the birth point of modern science and is a visual reference point for the break of the faith community with the scientific community. He represents the confrontation between doctrine and science. The Church and religious systems in general are still seen as the enemy of science and innovative thinking. This view prevails despite the repeated efforts for reconciliation by Pope John Paul II (mentioned later on this page). Galileo used a telescope to arrive at his support of Copernicius’ theory of a sun centred solar system and was silenced. Galileo’s legendary mumbling “Yet it moves” has made him the rally point for the split of faith and reason.

Early Life

Galileo Galilei was the first of seven children born to Vincenzo Galilei and Giulia Ammanati. His father was a cloth merchant as well as a noted musician who wrote several treatises on musical theory. The Galileis were a noble Florentine family that over the years had lost much of its wealth. It was for financial reasons that Vincenzo left Florence and moved to Pisa to establish his textile trade.

At the age of ten, Galileo and his family returned to Florence. His early education was directed by his father with the help of a private tutor. He also spent some time at the monastery of Santa Maria di Vallombrosa. The content of Galileo’s elementary education is unknown, but it was probably humanistic in character. His father urged him to pursue university studies which would lead to a lucrative profession.

Following his father’s wish, Galileo enrolled as a student of medicine at the University of Pisa in 1581. He showed little interest in his medical studies; it was mathematics that captured his attention. A year after enrolling at the university, Galileo made his legendary discovery of the isochronal movement of pendulums by observing a chandelier in the Pisa cathedral. He confirmed his theory regarding the equal movement of pendulums by conducting a series of experiments. He continued an independent study of science and mathematics, finally convincing his father to allow him to abandon his medical studies. Galileo withdrew from the University of Pisa in 1586 without receiving a degree, and he returned to his family.

Upon his return to Florence, Galileo studied a wide range of literary and scientific texts. In addition, he delivered a series of popular lectures on the Inferno of Dante’s La divina commedia (c. 1320; The Divine Comedy, 1802) at the Florentine Academy. In 1589, he used the influence of friends to obtain an appointment as a lecturer of mathematics at the University of Pisa. His return to Pisa marked a productive and enjoyable time for the young scholar. He conducted a series of experiments relating to falling bodies and wrote a short manuscript which challenged many traditional and generally accepted teachings about physics. In addition to his scholarly activities, Galileo was known for his quick wit, biting sense of humour, and excellent debating ability. Once again his friends intervened on his behalf to arrange an appointment, in 1592, to a more prestigious chair of mathematics at the University of Padua.

Astronomy

It was at Padua that Galileo began his life’s work which would bring him both fame and controversy. He quickly established himself as an excellent and popular teacher, both in terms of public lectures and private tutoring. He also wrote a series of short manuscripts on a variety of technical and practical issues. In 1597, he constructed a ‘military compass’ to assist artillery bombardments and army formations.

Although Galileo’s invention of the military compass brought him acclaim and a good source of additional income, it was his work in the study of motion and astronomy that firmly established his reputation as a leading scientist. In 1604 a new star could be seen, and its sudden appearance prompted a fierce debate. According to the dominant theory of the time, Earth was the immovable centre of the universe. Based on the work of Aristotle and Ptolemy, most scholars believed that the planets, sun, and stars rotated around a stationary Earth. The universe was thought to reflect a perfect and unchangeable order that had been created by God. The new star raised a problem of how to account for its presence in an already complete and perfectly ordered universe.

Discovery and Biblical Controversy

Through the use of his self-constructed leather telescope, Galileo was to discover sunspots, the moons of Jupiter, the rotation of Venus and the ‘ears’ of Saturn. Galileo was to write two small books in succession, The Starry Messenger in 1610, and in the following year he wrote The Sunspot Letters. He had confirmed Copernicus’ theory of a rotating, moving Earth and a relatively still sun. Tracts immediately appeared detecting a whiff of heresy in the conclusions. Galileo remained confident. He was a believing Catholic with two daughters who had become nuns; he was a personal friend of Cardinal Maffeo Barberini (destined to become the next Pope, Urban VII), and he was on personal terms with the influential Duke of Tuscany.

In 1614 a Dominican priest filed charges at the Office of the Inquisition. Galileo was to respond by writing extraordinarily long letters which were circulated and became subject of debate. The most influential churchman of his age, Cardinal Bellamarine was to say of Galileo’s theories: “a very dangerous thing, likely not only to irritate all scholastic philosophers and theologians, but also likely to harm the Holy Faith by rendering Holy Scripture false”.

The argument from scripture for an earth-centered system was founded on a very literal interpretation of several Old Testament texts. The sun’s apparent movement could be inferred from Psalm 19: 4-6 which says “the sun comes forth like a groom from his bridal chamber and … joyfully runs its course; or from Ecclesiastes 1:5: “the sun rises, the sun sets; then to its place it speeds and there it rises [again]”; or from Joshua 10:12-13: “Joshua declared, ‘Sun, stand still over Gibeon, and, Moon, you also, over the Vale of Aijalon.’ And the sun stood still, and the moon halted till the people had vengeance on their enemies.” The earth’s immovability seemed clear from Psalm 104:5: “You fixed the earth on its foundations, unshakeable for ever and ever.”

Foolish and Absurd propositions

Galileo believed that if the discussion were to go forward, it would be helpful to examine the Bible in a less mechanistic way. In this effort he showed a grasp of Scripture that was far ahead of his time – too far ahead, as it turned out. In a long letter to a friendly inquirer, he wrote,

“Though the Scripture cannot err, nevertheless some of its interpreters and expositors can sometimes err in various ways. One of these would be very serious and very frequent, namely to want to limit oneself always to the literal meaning of the words… It would seem to me that in disputes about natural phenomena, it [Scripture] should be reserved to the last place. For the Holy Scripture and nature both equally derive from the divine Word, the former as the dictation of the Holy Spirit, the latter as the most obedient executor of God’s commands; moreover in order to adapt itself to the understanding of all people, it was appropriate for the Scripture to say many things which are different from absolute truth, in appearance and in regard to the meaning of words I think it would be prudent not to allow anyone to oblige scriptural passages to have to maintain the truth of any physical conclusions whose contrary could ever be proved to us by the senses.”

Such subtleties made little impression in Rome. In 1615, The Sunspot Letters were examined for heresy. Two propositions were found to be false, although not attributed to Galileo. Cardinal Bellamarine summoned Galileo and read the declarations of the commission. From this, Galileo believed he was free to continue writing. Rumours spread and Galileo approached the Cardinal again for a clarification and obtained from him a signed certificate asserting that he had not been required to renounce under oath or in any other way his opinions. Galileo felt reassured and met with Pope Paul V. In 1623 Barberini was elected Pope Urban VIII and the new pontiff began having weekly meetings with the scientist, expressing genuine interest in his work.

Fourteen years later Galileo wrote his most important and controversial book, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published in 1632. Its purpose was to present an ‘inconclusive’ comparison between the Ptolemaic and Copernican models of the universe. Although Galileo carefully presented the various claims in terms of competing theories, it was apparent that he believed that the earth-centered theory was false and that the sun-centered theory was true. The book was structured in the form of a debate between three imaginary spokesmen, Salviatti, who believed the Sun-centred theory, Simplico, who believed the earth centred theory, and Sagredi, a kind of impartial host, referee and asker of intelligent questions. Galileo made an unfortunate blunder. The final words of the discussion by Simplico (a name that could easily be translated as ‘Simpleton’) were the very words that Urban VIII often used when asked about the Church’s stance on the new science: “It would be excessively bold if someone should want to limit and compel divine power and wisdom to a particular fancy of his.”

His book was to immediately receive wide acceptance and circulation, only to be suddenly barred by order of the pope himself. Urban moved quickly to appoint a commission to determine possible charges for the Office of the Inquisition. Galileo was warned ‘the sky is about to fall’ by his friend the Duke of Tuscany. The commission found ample evidence of charges for heresy. Galileo was at this time 70 years old and wanted to have the charges heard in Florence. He was losing his eyesight, had severe arthritis and suffered from bouts of colitis. He only agreed to go to Rome after officers of the Inquisition threatened to transport him there in chains.

Forced to Recant

When formal proceedings began, Galileo believed he could defend himself adequately. He still had in his possession the signed certificate that Cardinal Bellamarine had given him seventeen years before in 1616. Bellamarine had since died but the document said that Galileo had not been told to retract his views or to cease writing. He was simply informed that his views could not be presented as fact.

Questioning had hardly begun when his defences were breached. The prosecutors presented him with a copy of a ‘special injunction’ dated 1616 which utterly contradicted the Bellamarine certificate. It stated that the cardinal explicitly told Galileo that ‘his opinion was erroneous and that he should abandon it … and that henceforth he was not to hold, teach or defend it any way whatever (as fact or hypothesis) either orally or in writing …

… … When asked by his inquisitors had he failed to follow this injunction and not told the censors of his book of the injunction’s existence, Galileo insisted that he had neither seen nor heard of this document, which bore no signature, until the moment it was handed to him, and he had no memory of agreeing to such stipulations. Today, scholars view this document to be a forgery designed to trump the Bellamarine certificate held by Galileo.

Galileo was reeling in shock. He relented. He was given time to re-read his Dialogues, and, after being shown the instruments of torture, encouraged to write a judicial confession. Galileo wrote that he would weaken his theories so that they would lack any force. This was not good enough for the Inquisition, who wanted him to admit that he knew of the injunction and chose to ignore it. Galileo acquiesced. He was found ‘vehemently suspected of heresy’ and was sentenced to imprisonment at the pleasure of the Office of Inquisition.

Galileo remained in shock for several months. Pope Urban, his rage spent, quickly allowed the repentant heretic to depart the bleak accommodations of the Office of Inquisition in Rome and take up house arrest under strict conditions, first in the village of Sienna, and then later in his native Tuscany. His spirit, however, refused to be crushed, and with encouragement from his son, he began studying and writing again, achieving amazing productivity in the remaining nine years of his life.

Coda

For the rest of his life Galileo remained under house arrest. He was not allowed to take any extensive trips or to entertain many guests. Following the death of his favourite daughter in 1634, he lived a lonely life and became blind in 1637. Despite the attempt to isolate him from the world, his fame grew — such noted figures as Thomas Hobbes and the poet John Milton went out of their way to visit him shortly before his death in 1642. In 1757 after the accuracy of his research had been established beyond reasonable doubt, the Inquisition removed the ban on all books that taught the earth moves except those by Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler. The fallout from this continued to have a ripple effect all over Europe. The unshackled search for scientific truth was frequently accompanied by hostility to spiritual and religious truth.

Galileo marked an important break between theology and science that was not easily or quickly bridged — Copernicus (a Polish monk) and he were not removed from the Church’s index of banned books until 1835. Yet, despite his conviction for heresy, history has judged his right to seek after truth quite differently. According to legend, as Galileo signed his recantation following his trial, he mumbled, “Eppur si muove” (“And yet it [Earth] moves”). Although Galileo never spoke these words, this legendary mumbling has endured as silent witness of the Church’s mistakes and its split with the modern science movement.

Yet it Moves

‘And yet it moves‘ has inspired centuries of scientific research to the point of science now being able to ignite the elements of life in a pertri dish and fuse new life into existence. Stem cells are grown to replace defective organs, bones and muscles. Ethical arguments abound between the scientists and moral representatives of humanity (not always the Church) over what represents human life. Cloning is now attracting research dollars and concerned public debate. Most ethical enquirers have lost the plot about divinity being embodied (i.e., the soul) in a life form.

The scriptures of all religions have the five Human Values and seek to establish pathways for relationship with the divine and even, attainment of the Divine itself. Galileo’s contribution was to specify that scripture has a role and function in regard to faith and not in regard to the natural created order, although the world scriptures frequently do describe the source of the natural order correctly. in 1979, Pope John Paul II affirmed that Galileo’s understanding of sacred scripture and its position vis-a-vis scientific enquiry was correct.

Unhealthy Split

Humanity now suffers from the unhealthy split of religion and science. Science should not be the servant of consumerism nor manufacture. Many inventions for satellites and space shuttles have found their way into the household and become items of excellent utility. However, science itself, sans values may create what Shelley envisioned … the mad scientist Dr Frankenstein with his monster.

Was Galileo the cause of such a horrid tale? No, Galileo had a conscience and remained a loyal son of Holy Mother Church, a loyal son who investigated the natural order. Many Churchmen were intensely interested in his work. Later Popes would have used his military telescope in wars over the Papal States. The thirty years war was in progress during the life of Galileo. Pope Urban and Cardinal Richelieu were fomenting intrigues in France.

A loyal Scientist with discrimination

Galileo was a scientist with discrimination. He was astute enough to see where he had been beaten by the underhand chicanery of the Inquisitors at his trial. He exercised discrimination far ahead of his times in specifying the limits of Holy Scripture vis-a-vis the natural order. He continued to use that discrimination during his house arrest. It is this discrimination that has eluded or been ignored by the modern age of science. Modern science views Galileo simply as the hero against blind faith and the necessary split of faith and reason.

Reconciliation

During the Pontificate of Pope John Paul II, there has been considerable reconciliation between Church and science. In a speech given on 19 November 1979, for the centenary commemoration of the birth of Einstein, Pope John Paul II deplored the lack of understanding between Christians and the failure of the Church to perceive the legitimate autonomy of science. The Pope began by saying that Galileo and Einstein characterised an epoch of humanity. The Pope said that science had its own autonomy, and the collaboration between religion and science did not violate the autonomy of either. The pope made it clear that in the past, the church had acted outside its proper competence. The pope speaks about Galileo:

Filled with admiration for the genius of the great scientist, a genius in which there is revealed the imprint of the Creator Spirit, the Church, without in any way passing a judgement on the doctrine concerning the great systems of the universe, since that is not its area of competence,

The pope made reference to the church instigating needless contests and controversies in the past, and cited a church document which deplored these conflicts. The Pope went on emphasise the primacy of truth over technology and its uses: “ethics over technology, in the primacy of person over things, and in the superiority of spirit over matter”. Pope John Paul II further articulated a critically important model of science–technology–conscience, which would seek the true good of humankind and seek to serve humanity. Science should defend the misuse of its gifts and undue interference of all tyrannical powers. You may read Pope John Paul II on The Greatness of Galileo below.

The Pope went further. In 1992, the Pontifical Council for Culture, a Vatican Office responsible for the Catholic Church’s dialogue for the world of culture — the visual arts, science, literature and music, carried out a lengthy study culminating in Pope John Paul’s 1992 statement expressing regret for the way the Church had responded to Galileo’s theses. The Jubilee Year of 2000 had a jubilee day for Scientists.

From the Jubilee 2000 Magazine (Google translation, passim, extremely poor translation)

I point out to the incomprehension faced in the last centuries evokes unavoidably the figure of Galileo. It has presided the jobs of the Commission of study of the “Galileo Case” in the last stage that carried to the historical sitting of 31 October 1992. It believes, Eminence, that the Galileo case by now is definitively closed? The creed that, from part of the Catholic Church has been one honest effort of clarification on the vicissitude of the “Galileo case”. The scope of the Commission was not to rehabilitate Galileo who, closely speaking, was not condemned for heresy. Neither it was be a matter of an exercise of “self-criticism”, as it was said cynically in the totalitarian systems. It was dealt rather than to understand the facts, answering to three questions better: cos’ it has happened, like and because. In summary, the Church has tried to make light on the vicissitude and to honestly recognise with courage and humility the happened facts.

Science and Love

It has been said “Politics without principles, education without character, science without humanity, and commerce without morality are not only useless, but positively dangerous. Character is to be sought more than intellect”. Character, human values and discrimination are important. Science without love is blind science. Pope John Paul II has courageously worked during his reign to both pardon and rehabilitate Galileo, admit and deplore the abuses of the Church, and to reconcile modern science with divine love.

Portrait of Galileo

JOHN PAUL II

10 November 1979

The greatness of Galileo is known to all

During the centenary commemoration of the birth of Einstein, Pope John Paul II spoke on the profound harmony between the truth of faith and the truth of science. Discourse reprinted from Galileo Galilei. Toward a Resolution of 350 years of Debate – 1633-1983. Edited by Paul Cardinal Poupard. Translation by Ian Campbell. 1987. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. 195-200. © Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

>

>

The fundamental task of science

I feel myself to be fully one with my predecessor Pius XI, and with the two who followed him in the Chair of Peter, in inviting the members of the Academy of the Sciences and all scientists with them, to bring about “the ever more noble and intense progress of the sciences, without asking any more from them; and this is because in this excellent proposal and this noble work there consists that mission of serving truth with which we charge them”. 1

The search for truth is the fundamental task of science. The researcher who moves on this plane of science feels all the fascination of St. Augustine’s words, Intellectum valde ama,2 “love intelligence greatly”, and its proper function, which is to know the truth. Pure science is a good in itself which deserves to be greatly loved, for it is knowledge, the perfection of human beings in their intelligence. Even before its technical applications, it should be loved for itself, as an integral part of human culture. Fundamental science is a universal boon, which every nation should cultivate in full freedom from all forms of international servitude or intellectual colonialism.

The freedom of fundamental research

Fundamental research should be free vis-a.-vis political and economic powers, which should cooperate in its development, without fettering its creativity or enslaving it to their own ends. As with all other truth, scientific truth has, in fact, to render an account only to itself and to the supreme truth that is God, the creator of humankind and of all that is.

On its second plane, science turns toward practical applications, which find their full development in various technologies. In the phase of its concrete applications, science is necessary for humanity in order to satisfy the just requirements of life, and to conquer the various evils that threaten it. There is no doubt that applied science has rendered and will render humankind immense services, especially if it is inspired by love, regulated by wisdom, and accompanied by the courage that defends it against the undue interference of all tyrannical powers. Applied science should be allied with conscience, so that, in the triad, science-technology-conscience, it may be the cause of the true good of humankind, whom it should serve.

Unhappily, as I have had occasion to say in my encyclical Redemptor hominis, “Humankind today seems constantly to be menaced by what it constructs … In this there seems to consist the principal chapter of the drama of human existence today” (§ 15). Humankind should emerge victorious from this drama, which threatens to degenerate into tragedy, and should once more find its authentic sovereignty over the world and its full mastery of the things it has made. At this present hour, as I wrote in the same encyclical, “the fundamental significance of this ‘sovereignty’ and this ‘mastery’ of humankind over the visible world, assigned to it as a task by the Creator, consists in the priority of ethics over technology, in the primacy of person over things, and in the superiority of spirit over matter” (§ 16).

This threefold superiority is maintained to the extent that there is conserved the sense of human transcendence over the world and God’s transcendence over humankind. Exercising its mission as guardian and defender of both these transcendences, the Church desires to assist science to conserve its ideal purity on the plane of fundamental research, and to help it fulfil its service to humankind on the plane of practical applications. The Church freely recognises, on the other hand, that it has benefited from science. It is to science, among other things, that there must be attributed that which Vatican II has said with regard to certain aspects of modern culture: “New conditions in the end affect the religious life itself… The soaring of the critical spirit purifies that life from a magical conception of the world and from superstitious survivals, and demands a more and more personal and active adhesion to faith; many are the souls who in this way have come to a more living sense of God” (Gaudium et spes, § 7).

The advantage of collaboration

Collaboration between religion and modern science is to the advantage of both, and in no way violates the autonomy of either. Just as religion requires religious freedom, so science legitimately requires freedom of research. The Second Vatican Council, after having affirmed, together with Vatican I, the just freedom of the arts and human disciplines in the domain of their proper principles and method, solemnly recognised “the legitimate autonomy of culture and particularly that of the sciences” (ibid. § 59).

On this occasion of the solemn commemoration of Einstein, I wish to confirm anew the declarations of Vatican II on the autonomy of science in its function of research into the truth inscribed in nature by the hand of God. Filled with admiration for the genius of the great scientist, a genius in which there is revealed the imprint of the Creator Spirit, the Church, without in any way passing a judgement on the doctrine concerning the great systems of the universe, since that is not its area of competence, nevertheless proposes this doctrine to the reflection of theologians in order to discover the harmony existing between scientific and revealed truth.

Mr. President, in your address you have rightly said that Galileo and Einstein have characterised an epoch. The greatness of Galileo is known to all, as is that of Einstein; but with this difference, that by comparison with the one whom we are today honouring before the College of Cardinals in the Apostolic Palace, the first had much to suffer – we cannot conceal it – at the hands of men and departments within the Church. The Second Vatican Council has recognised and deplored certain undue interventions: “May we be permitted to deplore”, it is written in § 36 of the Conciliar Constitution Gaudium et Spes, “certain attitudes that have existed among Christians themselves, insufficiently informed as to the legitimate autonomy of science. Sources of tension and conflict, they have led many to consider that science and faith are opposed” … The reference to Galileo is clearly expressed in the note appended to this text, which cites the volume Vita e opere di Galileo Galilei by Pio Paschini, published by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.

In order to go beyond this position adopted by the Council, I desire that theologians, scientists, and historians, animated by a spirit of sincere collaboration, deepen their examination of the Galileo case, and, in a loyal recognition of errors, from whatever side they come. I also desire that they bring about the disappearance of the mistrust that, in many souls, this affair still arouses in opposition to a fruitful concord between science and faith, between the Church and the world. I give my full support to this task, which can honour the truth of faith and of science, and open the door to future collaboration.

The Case of the Scientist Galileo Galilei

May I be permitted, gentlemen, to submit to your attention and your reflection, some points that seem to me important for placing the Galileo affair in its true light, in which agreements between religion and science are more important than those misunderstandings from which there has arisen the bitter and grievous conflict that has dragged itself out in the course of the following centuries.

He who is justly entitled the founder of modern physics, has explicitly declared that the truths of faith and of science can never contradict each other: “Holy Scripture and nature equally proceed from the divine Word, the first as dictated by the Holy Spirit, the second as the very faithful executor of God’s commands”, as he wrote in his letter to Fr. Benedetto Castelli on December 21, 1613. (3) The Second Vatican Council does not differ in its mode of expression; it even adopts similar expressions when it teaches: “Methodical research, in all domains of knowledge, if it follows moral norms, will never really be opposed to faith; both the realities of this world and of the faith find their origin in the same God” (Gaudium et spes, § 36).

In scientific research Galileo perceived the presence of the Creator who stimulates it, anticipates and assists its intuitions, by acting in the very depths of its spirit. In connection with the telescope, he wrote at the commencement of the Sidereus Nuntius, (“the starry messenger”), recalling some of his astronomical discoveries: Quae omnia ope perspieilli a me exeogitavi divina Prius illuminante gratia, paucis abhinc diebus reperta, atque observata fuerunt. (4) “I worked all these things out with the help of the telescope and under the prior illumination of divine grace they were discovered and observed by me a few days ago”.

The Galilean recognition of divine illumination in the spirit of the scientist finds an echo in the already quoted text of the Conciliar Constitution on the Church in the modern world: “One who strives, with perseverance and humility, to penetrate the secret of things, is as if led by the hand of God, even if not aware of it”. (5) The humility insisted on by the conciliar text is a spiritual virtue equally necessary for scientific research as for adhesion to the faith. Humility creates a climate favourable to dialogue between the believer and the scientist, it is a call for illumination by God, already known or still unknown but loved, in one case as in the other, on the part of the one who is searching for truth.

Galileo has formulated important norms of an epistemological character, which are confirmed as indispensable for placing Holy Scripture and science in agreement. In his letter to the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, Christine of Lorraine, he reaffirms the truth of Scripture: “Holy Scripture can never propose an untruth, always on condition that one penetrates to its true meaning, which — I think nobody can deny — is often hidden and very different from that which the simple signification of the words seems to indicate”. (6)

Galileo introduced the principle of an interpretation of the sacred Books that goes beyond the literal meaning but is in conformity with the intention and type of exposition proper to each one of them. As he affirms, it is necessary that “the wise who expound it show its true meaning”.

The ecclesiastical magisterium admits the plurality of rules of interpretation of Holy Scripture. It expressly teaches, in fact, with the knowledge of who Galileo truly was, of the real message that he brought to the world. This message, like the fishing net of the Gospel, contains strengths and weaknesses, includes discoveries and errors; as a whole, however, it transmits a lesson that is still valuable today …

Notes

1 Motu Proprio In Multis Solaciis of 28 October, 1936, concerning the Pontifical Academy of Sciences AAS 28 (1936) 424

2 St Augustine, Epist 120,3,13; PL 33, 49.

3 Galileo Galilei, “Letter to Father Benedetto Castelli”, December 21, 1613; EN, V, 282-85.

4 Galileo Galilei, Sidereus Nuntius, Venetiis, apud Thomam Baglionum, MDCX, fol. 4.

5 Ibid.

6 Galileo Galilei, “Letter to Christine of Lorraine”, EN, V, 315.

This page last updated 7 October 2019

This page first updated 11 June 2003

© Saieditor.com

![]()