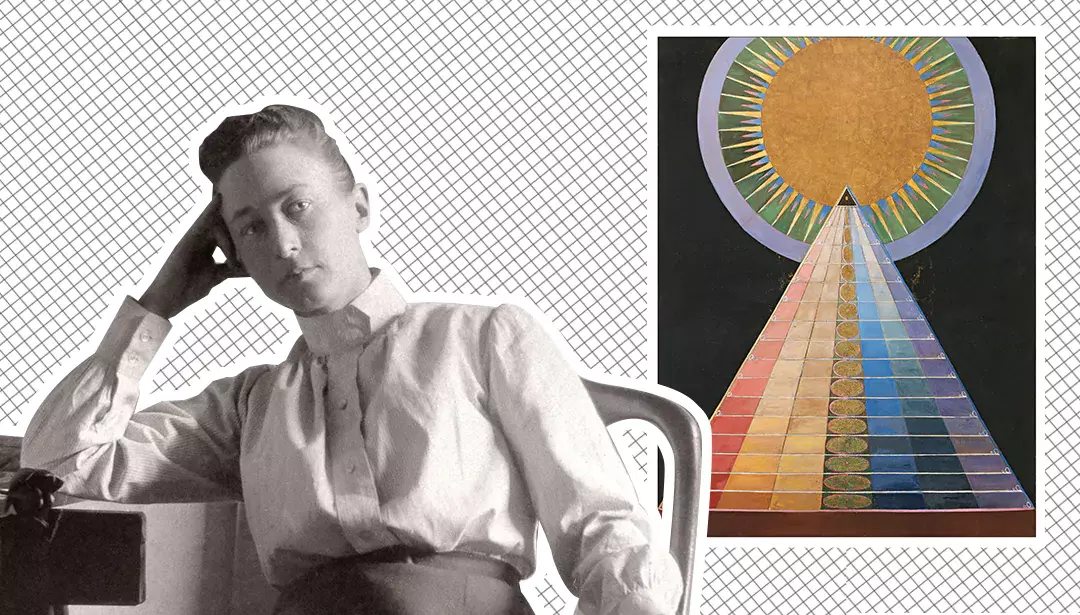

Hilma af Klint (October 26, 1862 – October 21, 1944) was a Swedish artist and mystic whose paintings are considered among the first abstract works known in Western art history. She belonged to a group called “The Five”, comprising a circle of women inspired by Theosophy, who shared a belief in the importance of trying to contact the so-called “High Masters” — often by way of séances. Her paintings, which sometimes resemble diagrams, were a visual representation of complex spiritual ideas.

Hilma af Klint (October 26, 1862 – October 21, 1944) was a Swedish artist and mystic whose paintings are considered among the first abstract works known in Western art history. She belonged to a group called “The Five”, comprising a circle of women inspired by Theosophy, who shared a belief in the importance of trying to contact the so-called “High Masters” — often by way of séances. Her paintings, which sometimes resemble diagrams, were a visual representation of complex spiritual ideas.

On October 26,1862, Hilma was born into a lineage of explorers, a family of naval officers and maritime cartographers in Stockholm. From an early age, she carried on the spirit of journeying and mapping distant worlds, devoting her days to diving into the mysteries of the sacred. Hilma believed that, “Life is a farce if a person does not serve truth.” While she kept company with close female friends and various esoteric communities, she never married nor birthed a family. She was deeply committed to her divine union with the unseen realms.

In 1879, at age 17, Hilma became interested in the Spiritualist movement and began participating in séances. One year later her sister Hermina died of the flu at age 10, making her more and more curious about what lies beyond the veil. Whatever Hilma found when she peered into numinous spaces kept her captivated until her last breath. While many mystics have expressed the rapturous experience of divine encounters, the capacity to document such magic lies in yoking the spirit realm with the material world, something Hilma achieved to mesmerising effect in her art-making practice.

In 1882, Hilma went on to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, one of the few places in Europe that permitted women to enrol in their programs at the time. lt was here that she learned the foundations in landscape and portraiture painting. Her propensity for endlessly dissecting the world around her lent itself to botanical painting, and these pieces were the only works she would share publicly in small groups and scientific journals.

Abstraction entranced her imagination, though, and despite being classically trained, it would be her esoteric studies and direct instruction from the spirits that would inform the greater part of her life’s work. Hilma’s journals record encounters with otherworldly beings during séances with a group of four women she met in the Edelweiss society. They called themselves “The Five” and would gather to sit in prayer, meditation and Christian scripture before invoking spiritual leaders that they referred to as the “High Ones”. The women would then transcribe what they heard and document their findings, filling pages of sketchbooks with intuitive drawings, some of which became the basis for the spiralled compositions in Hilma’s chaos series. Over the years it became clear that Hilma had a gift as a psychic medium and was committed to creating visual translations of esoteric knowledge. “All knowledge,” as one of the spirits, Gregor, transmitted, “that is not of the senses, not of the intellect, not of the heart but is the property that exclusively belongs to the deepest aspect of your being […] the knowledge of your spirit.”

In 1905, another of these supernatural guides named Amaliel commissioned her to make a body of work titled, The Paintings for the Temple. This inspired series saw Hilma initially create 111 paintings over the course of one and a half years, her petite five-foot frame becoming almost larger than life as these grand works danced out through her frenzied paintbrush. In her notebook, she explains her process while producing these paintings:

“The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict. Nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

Hilma also referenced the great responsibility that came with this heavenly commission: “This was the large work, that I was to perform in my life.” Before commencing the enormity of the task, she spent a year preparing by mentally and physically cleansing her body and mind. Receiving direction from Amaliel, she was instructed to undertake a retreat in isolation, eat a simple vegetarian diet, and focus her mind. This further enabled her to become a clear conduit for the work to pour through. This dedication to the translation of mystical experience and esoteric knowledge is what sets Hilma’s work apart from her fellow abstract painters of the modernist era. Hilma was less interested in dissolving the aesthetic norms of art, and more engaged in trying to convey visually encoded messages from beyond. Instead of looking to her peers or the Western art history canon for inspiration, or relying on her physical senses to describe her world, Hilma’s muses were intangible in nature. She had committed to tuning her inner senses, painting the mysterious murmurings that she heard from the universe.

While a mystical experience is inherently ineffable, the symbolism encrypted in Hilma’s art mirrors this and provides an evocative threshold for the viewer to experience their own intimate moment of unity with the Divine. Her work invites us to lean into the great mystery and, as the poet Rainer Maria Rilke would say, to “try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue“.

Hilma’s quest led her to join various spiritualist movements of the times, but it was her involvement with the Theosophical Society that would have the greatest impact on her art. In 1908, after completing the first portion of her Paintings for the Temple series, Hilma sought the advice of Rudolph Steiner, then head of the Theosophical Society (before later branching off to form his own philosophy and educational curriculum in Anthroposophy). Believing that Steiner might be able to assist her in interpreting the message in her works, she presented her series, only to hear that he too was unable to decode their meaning. He advised her to keep her work hidden from the public for another 50 years. The news prompted Hilma – who was already a perfectionist and had grown exhausted by the transcendent output of painting – to temporarily abandon the project for the next four years, resuming her botanical painting and looking after her ill mother.

Rudolph Steiner’s feedback didn’t dampen Hilma’s innate fortitude though, she went on to be prolific, producing over 1000 pieces in her career. In a sense, Steiner was merely reflecting back to her what the “High Ones” had already intimated in their orders to keep the work hidden; the world was not quite ready for her. In this current age where we are enamoured by success and selfies, perhaps what seems so inconceivable is the notion that ultimately, it wasn’t about her at all. Hilma was prepared to relinquish any accolades or fortune during her lifetime, instead ensuring that the work would be received in an era when it would have the greatest impact. In her séance notes, she had scribed to the spirits, “Teach me to listen and receive in humility the glorious message.” This sublime reminder to tune in – amidst the whirring white noise of a world that spins ever so quickly – might just be her greatest legacy.

![]()