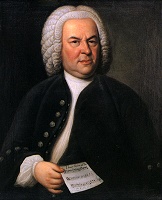

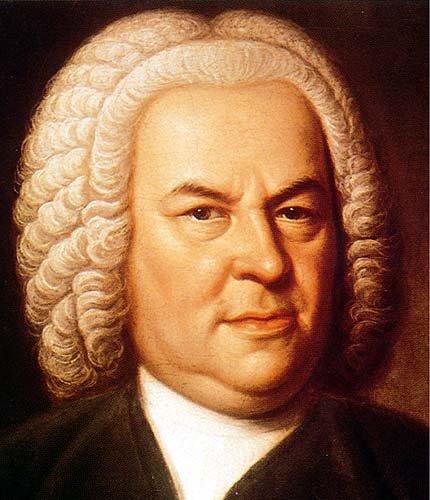

Johann Sebastian Bach was a German composer and musician of the Baroque period. In his childhood he was given an extensive religious education which was to profoundly influence his works, particularly where he obtained employment as organist and master of choir in various churches. He once wrote a short note to himself” “Where there is devotional music, God with his grace is present“.

Johann Sebastian Bach was a German composer and musician of the Baroque period. In his childhood he was given an extensive religious education which was to profoundly influence his works, particularly where he obtained employment as organist and master of choir in various churches. He once wrote a short note to himself” “Where there is devotional music, God with his grace is present“.

Introduction

Despite the majesty and mystery of his music, Bach’s life was mundane and uneventful. He was born in the German town of Eisenach in 1685. Unlike his more cosmopolitan contemporary Handel, he travelled little and was better known in his lifetime as an organist than as a composer. Typically for the large musical family into which he was born, his career comprised a series of court and church posts in which he acted as a general musical factotum: composing, arranging, conducting, teaching and playing organ, harpsichord and violin. He worked in Amstadt, Miihihausen, Weimar, Cothen and Leipzig, and this last appointment, as Kantor at St Thomas School and director of music at the town’s

main churches, was the longest, lasting for 26 years.

His Significance

In some areas of music in which Bach was active, for example, organ music, accompanied Christian liturgical music, and works for solo violin, Bach’s legacy either defines the field or towers over it. With regard to the fundamental musical technical discipline called “counterpoint”, the combination of independent melodies to form a harmonically and rhythmically vital union, Bach’s incomparable achievement dominates all of musical history, and is today the basis and touchstone for the entire discipline.

A Most Skilful Family

J S Bach came from an extraordinary family with an unusual concentration of musical talent which produced over 80 musicians in 8 generations between the 16th and 19th centuries. J S Bach himself recorded the details of his family tree. The generations of the Bach family lived primarily in the central region of Germany, in Meningen, Arndstandt, and Franconian. JS Bach himself was born in the region of Thuringia, a hilly region to the north of what is modern day Bavaria. Members of the Bach family found gainful work in town bands, as court musicians, or in service of the free cities or the Church – who made a reasonable rather than an opulent living from their skill and often married into other musical families. JS Bach, when he married a second time, married the daughter of a church trumpeter. A lively musical tradition flourished encouraged by the ambitious displays of magnificence of the small courts and by the individual towns need for prestige. The Bach family had a strong sense of having a musical tradition mixed with post Reformation zeal in the home country of Lutheranism.

The Times

The growth and decline of the Bach family was linked to social conditions. Initially with rapid expansion on account of musical practices in the courts, towns and churches toward the end of the sixteenth century – and then with the decline of the importance of the leading musical institutions such as the court orchestra. With the remarkable continued re-appearance of musical talent, members of the family taught one another. J S Bach taught Johann Lorenz Bach, Johann Bernhard Bach, Johann Elias Bach, Johann Heinrich Bach, Samuel Anton, and Johann Ernst Bach. The riches of musical talent culminated in J S Bach and thereafter, prominent musical members of the family began to decline.

The Bach family were aware of their history as bearers of a musical tradition. J S Bach systematically investigated the family history of births and marriages and its musical heritage. Nearly all were instrumentalists, mainly keyboard players, but virtually all instruments were represented. Most had learnt several musical instruments. Some were active in the craft of instrument manufacture. Early prominent members prior to J S Bach did not hand down compositions; composition of music at that time remained in the background and was reserved for those who had the necessary training – that generally meant the organists, who were expected to compose. Church Music for religious services was generally the responsibility of the Kantor. Some Bach family members supplemented their income writing Wedding Cantatas and Funeral Motets as a well paid side activity!

Composition for Christmas Day [written between 1713 – 1716]

1. Chorus (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass) Christians, etch ye now this day Both in bronze and stones of marble! Come, quick, join me at the manger And display with lips of gladness All your thanks and all you owe; For the light which here breaks forth Shows to you a sign of blessing. 2. Recit. (A) O blessed day! O day exceeding rare, this, On which the world's true help, The Shiloh, whom God in the Paradise To mankind's race already pledged, From this time forth was perfectly revealed And seeketh Israel now from the prison and the chains of slav'ry Of Satan to deliver. Thou dearest God, what are we wretches then? A people fallen low which thee forsaketh; And even still thou wouldst not hate us; For ere we should according to our merits lie in ruin, Ere that, must deity be willing, The nature of mankind himself assuming, Upon earth dwelling, In shepherd's stall to be a child incarnate. O inconceivable, yet blessed dispensation! 3. Aria (S, B) God, thou hast all well accomplished Which to us now comes to pass. Let us then forever trust him And rely upon his favor, For he hath on us bestowed What shall ever be our pleasure. 4. Recit. (T) Transformed be now today The anxious pain Which Israel hath troubled long and sorely burdened To perfect health and blessing. Of David's stem the lion now appeareth, His bow already bent, his sword already honed, With which he us to former freedom brings. 5. Aria (A, T) Call and cry to heaven now, Come, ye Christians, come in order, Ye should be in this rejoicing Which God hath today achieved! For us now his grace provideth And with such salvation sealeth, More than we could thank him for. 6. Recit. (B) Redouble then your strength, ye ardent flames of worship, And come in humble fervor all together! Rise gladly heavenward And thank your God for all this he hath done! 7. Chorus (S, A, T, B) Highest, look with mercy now At the warmth of rev'rent spirits! Let the thanks we bring before thee To thine ears resound with pleasure. Let us e'er in blessing walk, But yet / Let it / never come to pass That we Satan's torments suffer.

Childhood

J S Bach himself was trained as a violinist and organist. He was a genius of outstanding performance, creative in the use of instruments and as a young man of 15 or so, acquired a legendary fame as a virtuoso. It was his accomplishments as a composer that earned him his place in history. As a child, he attended the Latin school in the same town Martin Luther was born. He became a very good treble singer and sang under a Kantor at the Georgenkirke where his father played instrumental music before and after the sermon. His cousin played the church organ. Bach’s mother died in 1694. His father remarried in 1695 and died shortly thereafter. J S Bach and his older brother Jakob were taken in by his eldest sibling, Johann Christoph Bach and sent to school for several years. In 1700, Christoph’s wife was pregnant again, and expecting another child to feed. Christoph was unable to pay J S Bach’s school fees. Historical investigation has revealed Christoph trained J S Bach as an organist. At that same time JS Bach had learned on his own initiative to compose by copying other compositions.

A story is told of the young J S Bach: He travelled as young man from Eisenach to Luneburg where he schooled. He later on visited Hamburg, some 50 kilometres distant to see his cousin. He later returned to Luneburg penniless and rested himself outside an inn. Someone threw two fish heads at him [fish was considered a delicacy in Eisenach] so he picked them up to examine them and see if any edible morsels remained. Looking inside the heads, he found two ducats, which not only enabled him to eat at the inn handsomely, but also paid for a return visit to his cousin’s home in Hamburg!

Private Life

Little is known of Bach’s private life and character. He was twice happily married (his first wife died in 1720) and he had 20 children, several of whom became leading musical figures of the next generation. Many of the children, however, died shortly after childbirth or within two years. Apart from some youthful indiscretions at Amstadt – including involvement in a brawl and a reprimand for inviting an “unfamiliar maiden” into the choir loft – and periodic wrangles with the town council at Leipzig, he seems to have been a reliable and conscientious employee. None the less, though mindful of his inferior social position, he was not afraid to fight his ground when necessary on issues of pay and conditions. It was difficult for him and many other musicians of his time, for he often had three employers; the town council, the court, the church and sometimes even other patrons.

Kantor and Schoolmaster

The longest period in any one domicile of Bach’s working life was at Leipzig. Leipzig was a flourishing commercial city with about 30,000 inhabitants. There were five churches in Leipzig in addition to the University chapels; the most important were St Nicholas and St Thomas, at which Bach was responsible for the music. Bach’s duties as Kantor were a mixture of schoolmaster, director of music at both churches, and a composer for civic occasions. St Thomas’s school was an ancient foundation which took in both day and boarding pupils. It provided fifty-five scholarships for boys and youths who were obliged in return to sing or play instruments in the Sunday services of the four Leipzig churches as well as to fulfil other musical duties. Scholarship students chosen on the basis of musical as well as general scholastic ability.

As Kantor of the School JS Bach ranked third in the academic hierarchy and his duties included four hours of teaching each day [he had to teach Latin as well as Music]. He and his pupils provided the music at the four churches every Sunday, two of which had elaborate Sunday services including an elaborate cantata on alternate Sundays. For grander occasions he could augment the scholars with town musicians, but in general he was restricted to inadequate resources for what was a back breaking task. In his first years at Leipzig he wrote (or sometimes reworked) a cantata for every Sunday and major festival, composing about 150 between 1723 and 1727. Most of these are difficult to perform, vocally. Bach had the unusual gift of providing the exact musical imagery of the scriptural verse.

An example of Bach and skill in providing musical imagery is described:

For the First Sunday of Advent (Advent being the four weeks prior to Christmas, and a period of reflection on the coming of the Lord to the earth. The spiritual and theological focus is on the coming incarnation): Music is annotated as follows: The first recitative, on a stanza of uneven line-lengths announcing the coming of the Savior, borrows a technique from Italian opera—the cavata. This is the drawing (cavare) from the last line or lines of a recitative the text for a short aria passage. The first real aria, on a more formal iambic stanza, is a siciliano—another operatic genre, based on a folk dance—and uses a repetition dal segno, that is, a da capo that omits the first ritornello. Bach converts the welcoming of Christ to his church into a pastoral love song. The next recitative, composed on a prose text from Revelation 3:20, “Behold, I stand at the door and knock,” frames the words of Christ in five-part strings playing pizzicato to depict the knocking at the door. For the aria that follows Neumeister wrote a trochaic poem that voices the sentiment of the worshipper who, having heard Christ’s knocking, opens her heart to him. It is in the intimate medium of a continue aria with da capo. The final movement is a motet-like elaboration of the

Abgesang from the chorale “Wie schonleuchtet der Morgenstern” on the last lines of its last stanza, “Come, you beautiful Crown of Joy,” the crown being suggested in a wreath of violin figuration posed above the voices.

Despite Bach’s Lutheranism, his music has become a powerful expression of religious commitment to people of all denominations and faiths. In part this derives from his assimilation of a wide range of styles: secular dance and instrumental styles with the sacred Catholic polyphony of Palestrina and the simple pious melodies of the Lutheran chorale; but here he was merely fulfilling and extending the typically Lutheran rhetorical question: “Why should the devil have all the best tunes?”

The Passion Tradition

In the context of Baroque Music, a Passion (or, more formally, “Passion setting”) is a musical/dramatic treatment of the events of Passiontide, that is, the Last Supper, Betrayal, Arrest, Trial, and Crucifixion of Jesus, as related in the New Testament. “Passion” means “suffering”, from the Latin, patior, “I suffer”, nominal form passio, passionis. The tradition of Passion Music is many centuries old, going back to the Good Friday rites of the Roman Catholic Church. By convention and church canon, musical Passion settings are built around the Gospel text of one of the four Gospels for any given Passion setting. A “Passion according to St. X” is a Passion setting based on the Gospel of St. X. Hence, the term “St. Matthew’s Passion” is incorrect, as Jesus is doing the suffering, not St. Matthew. The correct terms are “The Passion according to St. Matthew by J. S. Bach“

An examination of the settings of the Passion according to St. John and St. Matthew:

These two works, essentially similar in structure, are the crowning examples of the North German tradition of Gospel Passion settings in oratorio style. For the St. John Passion, in addition to the Gospel story (St. John Ch 23 and Ch 19, with interpolations from St. Matthew) and fourteen chorales, Bach also borrowed words, with some alterations, for added lyrical numbers from the popular Passion poem of B. H. Brockes, adding some verses of his own. Bach’s musical setting, which was, probably, first performed at Leipzig in 1724, was subjected later to numerous revisions.

The St. Matthew Passion, for double chorus, soloists, double orchestra, and two organs, first performed in 1729 (or possibly 1727), is a drama of epic grandeur, the most noble and inspired treatment of its subject in the whole range of music. The text is from St. Matthew’s Gospel, chapters 26 and 27; this is narrated in tenor solo recitative and choruses, and the narration is interspersed with chorales, a duet, and numerous arias, most of which are preceded by arioso recitatives. The “Passion Chorale” appears five times, in different keys and in four different four-part harmonizations. The author of the added recitatives and arias was C.F. Henrici (1700-64; pseudonym, Picander, a poet and the Postmaster General of Leipzig), who also provided many of Bach’s cantata texts. As in the St. John Passion, the chorus sometimes participates in the action and sometimes, like the chorus in Greek drama, is an articulate spectator introducing or reflecting upon the events of the narrative. The opening and closing choruses of Part I are huge chorale fantasias; in the

first, the chorale melody is given to a special ripieno choir of soprano voices.

Nearly every phrase of the St. Matthew Passion affords examples of Bach’s genius for merging pictorial musical figures with expressive effects. Of the many beautiful passages in this masterpiece of music, four may be singled out for special mention: the alto recitative “Ah, Golgotha“; the soprano aria “In Love my Saviour now is dying“; the last setting of the Passion Chorale, after Jesus’ death on the Cross; and the stupendous three measures of chorus on the words “Truly this was the Son of God”.

The Passion According to St. Matthew is the apotheosis of Lutheran church music: in it the chorale, the concertato style, the recitative, the arioso, and the da capo aria are united under the ruling majesty of the central religious theme. While it is true that Bach never wrote an opera, nevertheless the language, the forms, and the spirit of opera are fully present in the Passions.

The St Matthew Passion was considered by Mendelssohn (whose revival of it in 1829 secured JS Bach’s reputation as a composer) to be “the greatest of Christian works”. It is also one of the greatest of all musical works, demonstrating technical mastery and a genius for stylistic synthesis through its combination of intricate contrapuntal writing, dramatic recitative, emotive arioso, dance style and the Lutheran chorale. Never before had such a range of compositional knowledge and such a depth of musical feeling been put at the service of church music. In the St Matthew Passion, Bach reveals his own feelings about the passion story in music of the greatest emotional intensity, which he reserves for the aria “Erbarme dich”. In the preceding recitative, Peter realises that he has thrice denied Christ, as predicted. The aria begs mercy of the Lord, confessing the bitterest remorse. By a masterly stroke, Bach avoids obvious dramatic realism, giving the aria not to Peter but to the alto soloist. Thus, in a way characteristic of the tendency of the whole work to contemplation, the aria transcends merely personal reflection of Peter’s state to become a regretful expression of human weakness with which all may identify. The voice is set against an accompaniment of sustained strings, the texture that accompanies Christ elsewhere in the work; so the aria is also the plea of Christ, now abandoned even by his closest disciple. At once, the strings and voice, a solo violin plays one of Bach’s most plangent, rhapsodic melodies in the melancholy rhythm of the siciliano. Perhaps in hearing this, we perceive the grace of God before human frailty.

Mass in B Minor

Bach’s profound spiritual conviction is the soul of his sacred works, and his genius may perhaps be called the perfect synthesis of music and theology. Nowhere is this genius better expressed than in this supreme legacy of his craft, the B Minor Mass.

The Mass is in a sense a retrospective of a lifetime’s work. It is not the product of one inspired moment, nor of any one particular period of his life. Bach completed the Mass near the end of his life, between 1745 and 1750–during the same period that he composed such vast monuments as “The Musical Offering” and “The Art of the Fugue.” Several movements of the Mass were anthologizations from earlier compositions which Bach had submitted to the Elector of Saxony, with the request that he be appointed court composer. Other movements he then composed, or adapted from other works in typical Baroque fashion.

Bach never heard the Mass performed in its entirety; possibly, he did not intend that it be performed on a single occasion. Like movements from the Well Tempered Clavier and similar compositions, Bach intended parts of the Mass to be used when appropriate. Such was the case when his son C.P.E. Bach first performed the Credo in 1786. Although various other sections of the Mass were performed for the next sixty years, it was not until 1859 (more than a century after Bach died) that the entire Mass was performed in Leipzig at a single sitting. In its complete form, it would have had no natural home in the Lutheran Sunday Service; instead, it stands as a musical last testament. Through it, Bach professes the truth of Music as a reflection of divine order that transcends historical circumstance and the differences between particular faiths.

Devotion and the End of his days

Toward the end of his life, cataracts covered his eyes, and his writings began to display the tell tale infirmities of old age. In 1749, Bach was blind and unable to write music. He died in Leipzig in 1750, leaving amongst his effects a significant number of theological books. These demonstrated deep commitment to the Lutheran faith, and in his copy of Abraham Calov’s annotated version of the Lutheran Bible, he added comments in the margins and underlinings,for his own use. One of these comments reads:

NB. Where there is devotional music, God with his grace is always present.

The list of Bach’s books compiled by curators after his death (his sons had taken all the musical works they wished for) was almost exclusively theological writings. There were tracts, pamphlets and sermons. Luther was represented, of course; there was a seven volume set of his complete works. There were books relating to the struggles between the Pietists and the orthodox Lutherans. There was a pamphlet on ‘Atheism’ and one on ‘Judaism’. Bach also owned a Biblical Atlas and Guide to the Ancient Lands. The closest to a non-religious book was Josephus, A History of the German War.

Bach remained an orthodox Lutheran throughout his life. From his early years as a composer, Bach often adopted the practice of heading his manuscripts with the words Jesu Juva&emdash;meaning Jesus, Help Me, and ended them with S.D.G.&emdash;meaning Soli Deo Gloria, to God alone the glory. In another place and in another age, and in this day and age, this is both namasmrana, (the repetition of the name of God), and nishkama karma, (offering the work and its fruits to God). These are devotional practices, ordinary everyday offering of works to God. Stradivarus did the same.

It is said that there are nine forms of devotion to the Almighty. Among those is numbered singing the glory of God, friendship with God, prayer, and service to the heart of God. These simple devotional practices of JS Bach form a profound spiritual centre wherefrom the creative urge, (which is nearest to the soul and derives 80% of its illumination from the soul), gains its traction for creation. One cannot promote the Glory of God and offer the works and grace to God alone and state the glory is His if one is not living close unto very God Himself.

JS Bach worshipped God via his vocation, which had sufficient discipline within it to create the experience, create the space, where others can be lifted up, out of themselves as it were to the polyphonic heights to “know and believe the love God has for us”. To write DEVOTIONAL music reflects a rare grandeur of personal devotion. Sacrifice is making that devotional music available for others, that they too may enrich their devotional life.

This work originally appeared on saieditor.com and is © Chris Parnell

![]()