I’ve seen two stage versions of English writer Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

One I saw in Glasgow in 2011 – an intimate, warm adaptation, with puppets for apparitions and a Scrooge speaking in broad Scots.

The other was at the Old Vic in London only a few weeks ago, a musical adaptation by Jack Thorne. This same adaptation is currently playing at the Melbourne Comedy Theatre, with well-known Australian actor David Wenham as Ebenezer Scrooge. Another production in Melbourne, by the Victorian Opera, relocates Dickens’ story to Federation Square and Flinders Street Station, making it contemporary and local.

Dickens’ story plays out every Christmas around the western world, but did it invent Christmas? Well, not exactly.

Key symbols of Christmas like the decorated Christmas tree were familiar to Europeans much earlier on, arriving in Britain (from Germany, in this case) early in the 19th century.

The weird world of Christmas traditions

The Christmas spirit of feasting and hospitality had also been celebrated before Dickens. Sir Walter Scott’s festive poem Marmion written in 1808 – “We’ll keep our Christmas merry still!” – has its “plum-porridge” and “Christmas pie”, eaten as carol singers outside “roar’d with blithesome din”.

The American writer Washington Irving’s Christmas stories written between 1819 and 1820 also presented scenes of feasting, carol singing and houses “groaning under the weight of hospitality”.

In fact, Irving was a major influence on Dickens. His popular Christmas at Bracebridge Hall was already nostalgic for older English traditions and “the genial and social sympathies which constitute the charm of a merry Christmas”.

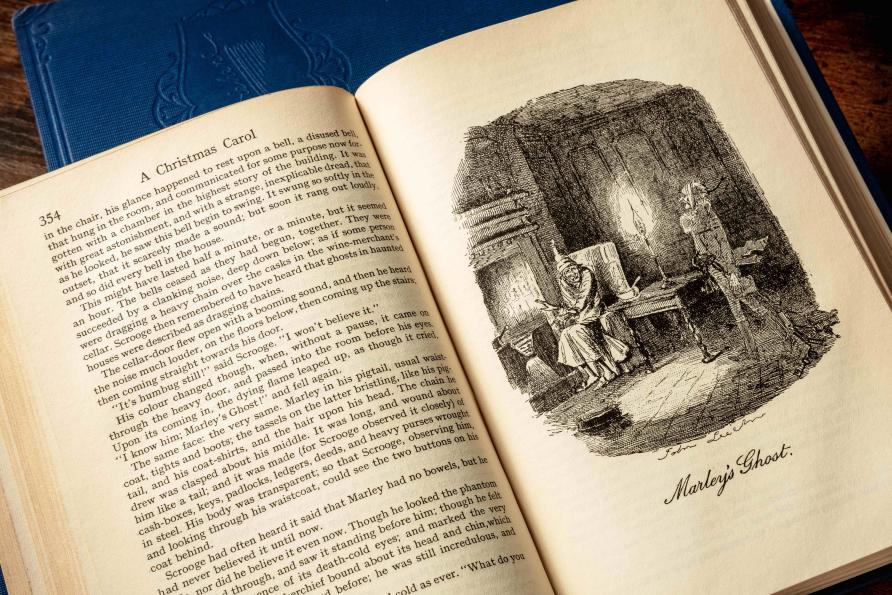

But Dickens’ A Christmas Carol published in 1843 certainly helped to popularise Christmas as an event.

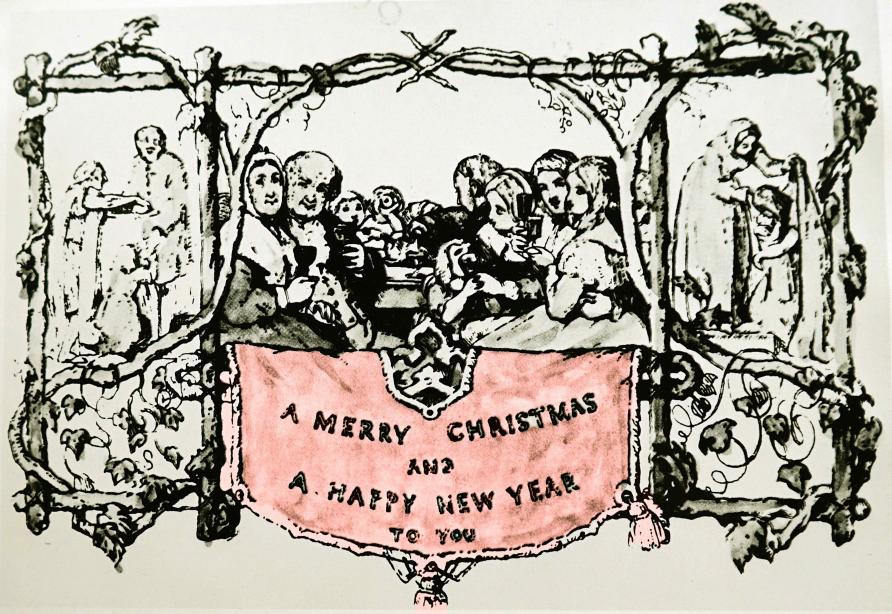

Interestingly, the Christmas story was published in the same year as the first commercial Christmas card, designed by English inventor Sir Henry Cole and the artist J.C. Horsley. (Sir Henry is best remembered today as the first director of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.)

A thousand copies of the festive card were printed, featuring a large family (including children, controversially) drinking Christmas punch around a table, with shadowy images of charitable assistance to the poor in the background.

Alcohol certainly played its part in Dickens’ Christmas story.

I’m dreaming of a…

In his vision of Christmas present, Scrooge sees “seething bowls of punch, that made the chambers dim with their delicious steam”.

And Dickens was himself fond of Christmas punch. In an 1847 letter, he presented his recipe: some brandy, a “pint of good old rum”, the rinds of three lemons and some lump sugar. The liquid is set alight for a few minutes and then boiling water and lemon juice are added.

But even this wasn’t Dickens’ own invention.

Punch had been around since at least the 1630s, with its origins in India and the spice trade routes to the west. It is said to derive from the Hindustan word paanch, meaning “five”, the number of ingredients used: spirits, water, lemon, sugar, and the spices themselves.

Both Cole’s Christmas card and Dickens’ story contributed to the popularisation of Christmas as a particular kind of quasi-religious event: social, not sombre like a Church gathering but “merry”.

We’ve already seen the word merry in Sir Walter Scott and Washington Irving’s writings.

Early 19th century collections of Christmas carols – by English writer and satirist William Hone in 1823 or solicitor William Sandys in 1833 – included God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen, generally agreed to be (as one historian put it in 1885) “the most popular of Christmas carols”.

In fact, this carol had also been around for a while, with the phrase of the title appearing in various earlier sources – like Shakespeare’s As You Like It (“God rest you merry, sir”), where the place of the comma slightly alters the meaning of the sentiment.

Focusing on kindness, not consumption, this Christmas

In Dickens’ story, it’s the first carol Scrooge hears on Christmas Eve. It makes him so angry that the singer “fled in terror”.

Dickens, on the other hand, heavily invested in what he called “Carol philosophy”, defined in an 1845 letter to his friend John Forster as “cheerful views, sharp anatomisation of humbug, jolly good temper”.

Scrooge, of course, thought that Christmas itself was humbug, an odd word that has its origins in Oxbridge student slang around the 1750s, where hum meant a hoax or a trick.

Christmas here is a kind of conspiracy and Scrooge is a bit of a conspiracy theorist. He thinks Christmas is an orchestrated interruption to his daily work as a debt collector in a counting house, a collective hoax played on the hard-working capitalist.

But Dickens wanted the Christmas spirit to reach right across the entire year, and to repeat itself annually. He knew a lot about debt. In fact, Dickens was debt-ridden when he wrote A Christmas Carol; like Cole and his Christmas card, Dickens wanted to see a lot of copies printed, and sold.

The success of A Christmas Carol encouraged him to invest in the genre of the Christmas ghost story or Winter’s Tale, and he published a number of them over the next few years: The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth, and so on.

In most of these stories, a lonely, miserly figure is haunted by visions that encourage him to become social and generous. Christmas is a time for sharing, not hoarding.

They offer an inverted, almost carnivalesque world, where even the poor, just for a moment, might be well-fed, festive and “merry”.

Shakespeare and lost plays

The ideological inversion of Dickens’ Christmas story is especially important. An otherwise mean and heartless employer – think of Twitter’s Elon Musk recently booed off stage following widespread layoffs or, indeed, any wealthy institution that axes workers at the festive end of the year – is blighted, and converted, by bleak visions of the devastation caused by heartless capitalism.

“I’ll raise your salary”, Scrooge finally says to his clerk Bob Cratchit, “and endeavour to assist your struggling family…”.

While Dickens may not have invented our modern Christmas, he has helped to redefine it.

That spirit is relevant even in 2022: as gas bills increase, interest rates go up and people turn more and more to charitable help, we might hope those ungenerous bosses out there are still getting an annual visit from the ghost of Christmas yet to come.

Banner: The Christmas Hamper by Robert Braithwaite Martineau/Alamy

“This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.”

![]()