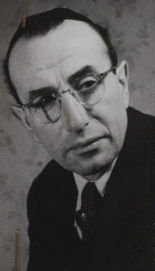

Martin Riesenburger was a German Cantor married to a Christian during WWII, and lived in Berlin. During WWII, he was given protected status and was allowed to function as Cantor and Rabbi at Weissensee, the old-age home that had a chapel and a Jewish burial ground attached to it. He survived the war and became Chief Rabbi of East Germany. Some revile Rabbi Riesenberger, some have sympathy for his role and his courage. We present a simple history of Rabbi Martin Riesenberger, the “Last Rabbi in Berlin” as a candidate for Saints of a New Era.

Martin Riesenburger, as far as it is known, was a native of Berlin, married to a Christian convert to Judaism. But little in Rabbi Riesenburger’s pre-Holocaust life suggested that he would become a rabbi, let alone a hero of the Holocaust. He had no ordination, no great oratorical ability and apparently little skill in Hebrew. He was going to be a dentist, but failed. He died in 1965, childless. Many facts about Rabbi Riesenburger’s life are sketchy. There are few extant records. The Holocaust claimed many witnesses to Rabbi Riesenburger’s deeds.

Berlin, Weissensee Cemetery

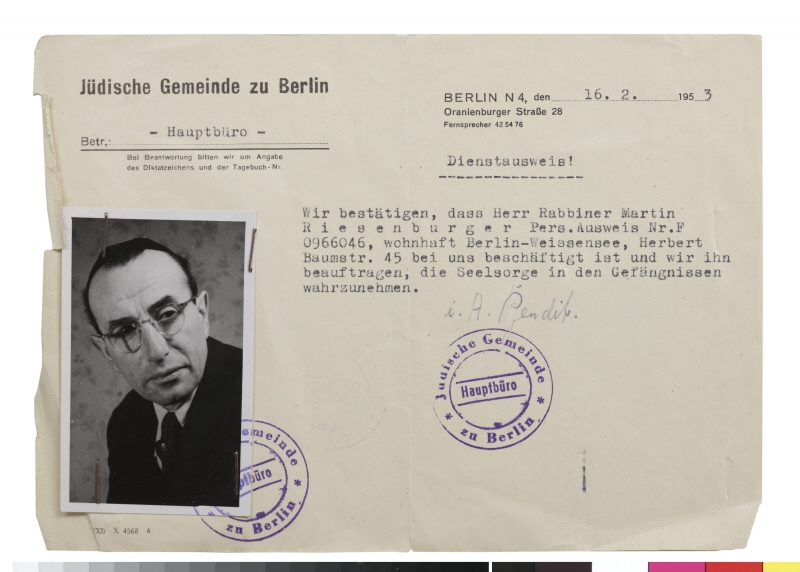

By the 1930s, Rabbi Riesenberger was working at Weissensee, the old-age home that had a chapel and a Jewish burial ground attached to it. Through the war, Jewish communal life in Berlin was increasingly strangled, immigration to the West being replaced by deadly deportation east. Although the capital was officially declared judenfrei (free of Jews), in June 1943, several thousand Jews still lived there. The number included forced labourers, mischlinge, (men married to Christian women), and Jews in hiding. These were Rabbi Riesenburger’s ‘congregation’, along with the Gestapo, who never failed to attend.

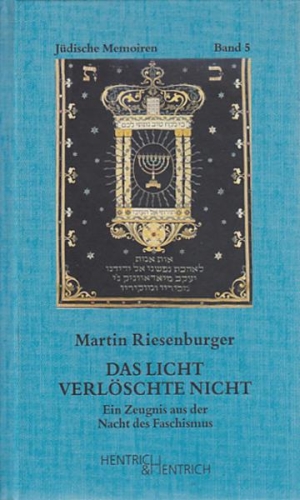

He wrote an autobiography, The Light that Never Fails. At first he was a preadiger, a preacher, and was also a cantor, who played the organ on Sabbath. This was before he took up the burial work. During World War II, Rabbi Riesenberger functioned as a member of the clergy, leading worship services and officiating at funerals. His activity was not a clandestine one. Little by little, people began to call him Rabbi.

The Light That Never Fails, Book Cover

Leading Services

Rabbi Riesenburger started leading Friday – night services each week in the chapel. With no printed announcements, word of Rabbi Riesenburger’s work spread by word of mouth. Rabbi Riesenburger was lumped in with all other persons of Jewish identity and made to wear the yellow star. He would lead a brief service, mostly in German, followed by candle lighting and kiddush. A few prayers and a sermon. He would always have a sermon. It was over in 15 minutes. Rabbi Riesenburger counselled the Jews who attended, he answered their questions on the phone, day and night. He surreptitiously made and distributed copies of the Hebrew calendar, with the dates of the Jewish holidays, on which occasions he also led services.

His denominational affiliation is unclear, but he probably did not identify himself as Orthodox. He did things that were ‘Liberal’ [the German name for the Jewish reform movement], playing the organ on the Sabbath. He did things that were Orthodox – washing the bodies of deceased Jews according to traditional custom, and wrapping them in shrouds, usually ersatz shrouds of newspaper. During services, the rabbi’s head was covered. The German Liberal Jews always wore a kipa [a traditional head covering]. The authorities did not perceive the ‘rabbi’ was a threat to them. Rabbi Riesenburger had no particular standing in the Jewish community, no independent source of power. Aware of a Jew’s precarious position in the Third Reich, he was ‘careful’ not to make any imprudent public statements.

But Riesenburger had a source of protection: his wife. She was born a Christian, and even though she converted to Judaism in the 1920s, she still was regarded as Aryan under Nazi race laws. As her spouse, Riesenburger, like several thousand other Berlin Jews, was spared deportation to a concentration camp. In late 1942, the Gestapo announced it would close the old-age home and deport its residents. Riesenburger held a final service in the home’s synagogue.

“I made a short speech, interrupted by the crying of those present, he recalls in his autobiography, Das Licht Verloschte Nicht (The Light That Never Failed). When it was over, we all shook hands, because we could not speak.”

Gestapo Takes Over

Working quickly – furniture was tossed out the windows, straw thrown on the floor – the Gestapo turned the home into a detention pen for Jews. This was the work of Alois Brunner, an ambitious young Gestapo official who had quickly and ruthlessly deported Vienna’s Jews. The deportation of Berlin Jews was going too slowly, and Brunner’s mission was to make the city Judenfrei.

Riesenburger was arrested, taken to the old-age home and locked in the same room where he’d once presided over a ceremony marking a couple’s golden anniversary. After a week he was called in to see Hauptsturmfuhrer Brunner. In his autobiography, Riesenburger says only that Brunner told him to resume his work, then released him. Assigned to another synagogue, he held services at which Gestapo agents often outnumbered Jews. The latter realized, Riesenburger wrote, it was only a trap.

In June 1943, Riesenburger secretly married a Jewish man and woman. He was 40, she 37. A few days later they were deported to a camp. It was the last marriage Riesenburger performed during the war; after that, there were only funerals.

Although Berlin had been declared Judenfrei, about 7,000 Jews still lived there. Some were underground; some were special workers; some, like Mr. Riesenburger, were married to Aryans. When these Jews died they had to be buried. The Nazis didn’t want Germans to do it, so they assigned Rabbi Riesenburger to Weissensee, the largest and now the only remaining functioning Jewish cemetery in Berlin. Rabbi Riesenburger seems to have been appointed for two reasons: because he was protected, and because he was nobody.

Toleration of Burials

Time and circumstance had removed the great spiritual and intellectual monuments of the German rabbinate. That left Mr. Riesenburger, a warm, unpretentious man who liked to read his wife Bible stories. He wasn’t even an ordained rabbi. He was a cantor, a vocation founded on his two early loves: God and music. Martin Riesenburger began giving Jewish Burials.

At first, he performed several funerals each day. Many were suicides, including people who had received a summons to Gestapo headquarters. Often, remains arrived in the mail in an urn, with a return address at Auschwitz or Buchenwald. They came C.O.D. Mr. Riesenburger prepared the body for burial, led the small funeral procession, said the prayers and played the organ. He always gave a eulogy. He did it not by mentioning current events — he never even alluded to politics — but by preaching hope, by stressing that there was something eternal that nothing could extinguish.

Life was tense and difficult for protected Jews, even in the cemetery. The Gestapo had invaded other grave yards to catch fugitives (they were hanged on the spot), and agents watched Weissensee’s entrances. Yet Rabbi Riesenburger went further. One day a truck pulled up to the gate. The driver hopped out and said he had a pile of Torahs in back: “Please be quick, I have to be off!”

Spies were everywhere. Rabbi Riesenburger roused his employees. “We have a special job,” he said. They loaded the Torahs onto carts, wheeled them inside, and hid them in the choir loft of the mourning hall. They packed them so high that by the end they had to stand on some Torahs to add more to the top of the pile. In all, Mr. Riesenburger hid or buried more than 500 Torahs. His goal, he said, was to remind survivors “that Berlin Jewry did not cease to exist.”

Jewish Services

Before the high holy days, some of Berlin’s remaining Jews, including those posing as Aryans, began to call the cemetery to inquire, elliptically, if there would be services. So Mr. Riesenburger began holding them secretly. He made copies of his Jewish calendar and slipped copies to people so they’d know when the holidays fell. They met downstairs in the yellow brick administration building. Gates were locked, a lookout posted. The services usually were attended by about 14 people, all afraid. Soft as their prayers were, Mr. Riesenburger told his followers, they were heard. “Quietly and silently,” he later wrote, “the embers glowed underneath the cemetery.”

In February 1945 the Riesenburgers were bombed out of their apartment house. So they moved to the cemetery, living on the second floor of the administration building. Their neighbour was the grave digger. Now, although Mr. Riesenburger rarely left the cemetery, he had less and less to do there. Burials had dropped from 3,257 in 1942 to 228 in 1944. It was a gloomy, desperate time. “We stood,” he wrote, “between the living and the dead.”

After the deportations began, Nazi and state attitudes towards Jewish suicides underwent a fundamental transformation. No longer did the Nazis encourage Jews to commit suicide. Suicide was not a criminal offence in Nazi Germany, despite Nazi attempts in the 1930s to criminalise it. During the war, the Nazis increasingly regarded themselves as the final arbiters over the lives of Jews. The knowledge that deportation meant death spread quickly among German Jews. Indeed, according to a list of funerals at the Jewish cemetery in Weissensee, 811 bodies of Jews who had committed suicide were buried there in 1942, compared to only 254 in 1941. On 23 March 1943, Martha Liebermann, the widow of the painter Max Liebermann, aged 85, was interred in this cemetery. She had committed suicide after receiving her deportation order. Riesenburger, The Light that Never Fails, pp39-40.

Then, in April 1945, the cemetery workers heard Soviet artillery to the east. Soon, shells were flying overhead. The Riesenburgers’ retreated to a crude bomb shelter below the administration building. After a while they heard men’s voices outside the cemetery door, ordering: “Open up!” Next, they heard several shots, followed by a silence that stretched, second by second, until dawn. When he emerged, Mr. Riesenburger found two black uniforms lying on the ground. The men outside had been SS, Hitler’s bodyguard. There were bullet holes in the cemetery door. Not long after, the Soviets arrived. When the first soldier came through the gate, Mr. Riesenburger recalled, “we embraced this messenger of freedom. We kissed him and we cried.”

Begins Religious Leadership

On a Friday night a few months later, a few Jews who had drifted back from the camps gathered in an old synagogue youth chapel in west Berlin. It was the Sabbath, but they did not come for services. They had no rabbi, no Torah, no prayer book, just this room they’d cleaned up. The synagogue itself had been burned down by the Nazis. Then a man appeared in the doorway. No one had seen him before. He introduced himself as Rabbi Riesenburger. If you want prayer books, I have some, he said. I’ll bring them to you next week. He brought a suitcase full. The prayer books led to services, which led to the first bar mitzvah and the first wedding. At Rosh Hashana, Mr. Riesenburger preached. As usual, he made people cry. No one seems to recall what he said, but several people make roughly the same remark: “to make us cry, after all we were through, took something special”.

Post-War Reconstruction

The majority of German survivors were bound to the country by their non-Jewish husbands and wives (as was Rabbi Martin Riesenburger) and felt indebted to the (German) social networks which had kept them alive; their connections to Judaism or the Jewish community were often only tenuous.

The eastern Europeans were generally more devout, but for the most part, did not identify as Germans. They had not intended to stay in the country of their persecution, but while some were too old and frail to emigrate, others would soon find themselves profiting from the German economic miracle and not want to leave a country when business was booming. While sitting on packed suitcases – as the generation of Holocaust survivors in Germany frequently explained – they inadvertently founded Jewish communities across Germany.

The history of the German-Jewish community post war is noted with difficulties experienced by postwar community leaders in finding and hiring Rabbis and religious educators. Few of the Jews had the necessary background to perform either of these tasks. And qualified Rabbis from abroad were not easily persuaded to move to Germany.

Riesenburger was the (non-ordained) religious leader of the East German community. He had but two years of training in Torah studies and was unable to decipher Hebrew letters without the punctuation – making it impossible for him to read from the Torah, which does not have punctuation marks in its scripture.

Rabbi Riesenburger never left East Berlin. The East German Communist government, (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or SED), eager to reject the Nazi legacy, recognized Mr. Riesenburger as the nation’s chief rabbi. This had its consequences, insofar as the SED argued that the GDR represented neither the legal nor historical successor of the Third Reich. Restitution of confiscated assets, rebuilding of war-damaged synagogues and damaged graveyards was not on the agenda.

In 1947, a letter written to the Soviet Military Administration from the German Jewish community noted, inter-alia,

“Just recently, tombstones the Jewish cemetery in Berlin-Weissensee were damaged and knocked over without any prosecution of the perpetrators.”

In that same year, the Berlin Jewish Community reported destruction at another Jewish cemetery in the small town of Oranienburg just outside the city.

Much like with the return of Jewish property, the importance and attention paid to the preservation of Jewish sites shifted over time. In the immediate postwar years, some local SED leaders argued for the preservation of Jewish sites as a small way to make amends for the Nazi past. In East Berlin, the SED faction of Berlin’s city council proposed a measure allotting 100,000 marks for cemetery repairs and the building of a monument in memory of the Jews at the historic Jewish cemetery in Berlin-Weissensee. Though consisting only of a small plaque, the memorial became the central site of remembrance for the German Jewish Community throughout the history of the GDR.

Rabbi Riesenburger defended the regime and criticized West Germany. Insofar as he was known at all in the West, it was as “the Red Rabbi.” Pressure was brought to bear on the rabbinate in Hungary to ordain him officially. He was the Chief Rabbi of East Germany. It was done.

There was more. In his letters he used his new position as Chief Rabbi of East Germany to communicate with the authorities in West Germany against the dangers of admitting to positions of responsibility any of those who had perpetrated atrocities against the Jews.

Rabbi Riesenberger was appointed Rabbi of what is now the largest synagogue in Berlin, Rykestrasse Synagogue.

In 1953, just after the split of the Berlin Jewish community, the city agreed to give the newly formed East Berlin Gemeinde 300,000 marks for the rebuilding of the synagogue on Rykestrasse, constructed in classical and local styles inspired by the nearby brick churches of the Mark Brandenburg area. The Magistrate decided to assist the Gemeinde not for any architectural or preservationist reasons – not because the synagogue represented a monument of the German past worthy of protection – but for largely practical and political concerns. In January 1953, the Gemeinde had between 45,000 and 52,000 marks in its account. Well aware of the organization’s scarce financial resources, the city justified its decision in stricty practical terms. Since Rykestrasse was the only functioning synagogue in East Berlin, the Magistrat agreed to supply money for a project that was necessary for the community’s survival.

The synagogue, being the sole functioning synagogue in the eastern sector of Berlin, underwent an extensive renovation and Riesenburger re-inaugurated it on 30 August 1953, giving it the name “Temple of Peace” (German: Friedenstempel). (Source:wikipedia.) This synagogue was later rebuilt in the 1990’s with a full reconstruction.

The Encyclopaedia Judaica does not include a single reference to Rabbi Riesenburger, and it has just one allusion to his activities under Nazi persecution: The Jewish cemetery had remained in use. When Martin Riesenburger passed, it was with the title of Rabbi. He died in 1965, and was largely forgotten. Modern historians criticise Rabbi Riesenburger for being too close to the SED, the ruling party of the GDR. History must take the long view, consider the forcible advance of Communism, further anti-Semitism in East Germany and refusals of the SED to restore and rehabilitate Jewish religious articles and property. But what of a spiritual point of view, that reason for hope in the human breast? We keep in mind the title of his book, The Light that Never Fails; it is a long, long journey of fidelity and service to the Divine to come to this realisation and live it in the midst of threat, terror, war and death.

Struggle and Hope

In times of extreme conditions of human existence, discipline is often the only thing that transcends such extreme experiences and situations, filtered with fear, stress and uncontrollable violence. It is discipline of belief that underlies ritual and empowers simple rituals [on the surface often just words and actions] to aid man in making sense out of growing horror, such as Shoah [the Holocaust] became. Hence “Rabbi” “Cantor” “Praediger” Martin Riesenburger preached on what could never be extinguished … the great gift that the people of the Covenant, recipients of the Law of God, the Law of Moses, the Torah. This great gift was a binding relationship, and in simple and human rituals of death, Martin Riesenburger recalled that the People of the Covenant possessed the light of lights, the light that never fails. The light that is the spark of God in the heart of man.

This work recently appeared on narayanaoracle.com and is © Chris Parnell

![]()