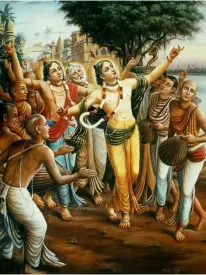

Chaitanya, also spelled Caitanya – more formally known as Sri Krishna Chaitanya, also called Gauranga. His birth name Vishvambhara Mishra, (born 1485, Navadvipa, Bengal, India – died 1533, Puri, Orissa), was a Hindu mystic whose mode of worshipping the god Krishna with ecstatic song and dance had a profound effect on public devotional activities in Bengal. Chaitanya was also instrumental in interfaith activities bringing about the re-creation of Brindavan.

Chaitanya, also spelled Caitanya – more formally known as Sri Krishna Chaitanya, also called Gauranga. His birth name Vishvambhara Mishra, (born 1485, Navadvipa, Bengal, India – died 1533, Puri, Orissa), was a Hindu mystic whose mode of worshipping the god Krishna with ecstatic song and dance had a profound effect on public devotional activities in Bengal. Chaitanya was also instrumental in interfaith activities bringing about the re-creation of Brindavan.

With a group of friends, he launched a movement based on the singing and chanting of divine names, which caught the imagination of the masses. He and his companions soon ran foul of the the ban on the public display of religious practice, with its violation resulting in severe physical punishment and, many times, in death.

Here, Chaitanya was challenged by the opposing power. History is full of such instances and also records rebellion towards others, in most cases violent rebellion. Chaitanya chose to rebel, but differently. Violent response as a solution has endless chain reactions and thus brings continual destruction. Chaitanya rebelled not because of religious discrimination or persecution. For him, it was a denial of the fundamental human right, i.e., freedom of his faith-practice. Bereft of political and economic power, Chaitanya adopted the path of peaceful disobedience. “Ihe greatest power a human being has is to say no to injustice of any kind. He then succeeded in persuading the ruling Islamic authority to restore the freedom of religious expression, especially in public.”

His contributions were many: however, from the point of view of interfaith relations, his greatest contribution was the re-establishment of Brindavan, the theatre of Krishna’s love dance. One of the holiest centres of Hindu faith, Brindavan, was a gift from a Muslim Mughal emperor to the Hindu Goswamis. This is a unique and unparalleled case of interfaith relations, where a holy centre of a faith (Hindu) was literally created and gifted by another faith (Islam).

This was made possible through the interfaith sensitivity of Chaitanya. In 1515, Chaitanya made a long pilgrimage from the eastern shore of India to the northern heartland, in order to visit the place of Lord Krishna’s leelas and sports, Brindavan. This sacred place to Hindus had an overwhelming presence in religious, literary, and artistic traditions, though it lacked a physical, geographical corollary. This sacred area of Braj, with lost Brindavan as its heart, in the early sixteenth century, was the marching route of the invading armies between Agra and Delhi. Chaitanya, during his nine-month-long stay in Braj, almost lost his life twice due to the hostilities. He faced the challenge first-hand.

Chaitanya responded to this volatile situation not violently, but with a well-thought-out plan of peaceful dialogue with the other. To that end, he created a team known as the Six Goswamis. Its three most prominent members came from a Muslim background, holding high positions in Hussain Shah’s court. After Chaitanya’s appointment, which involved no ritual conversion back into the Hindu way, they were most identified with their Hindu names as Sanatana Goswami, Rupa Goswami, and their nephew Jiva Goswami. The fourth belonged to a lower caste. The other two members held powerful priestly positions.

These Goswamis, as per Chaitanya’s guidance and plan, engaged with the imperial Mughal court. This was a Hindu-Muslim dialogue, but more importantly, a sincere dialogue of religious and political powers. The Goswamis engaged with the imperial Mughal court, with the mediation of Hindu Rajput kings and nobles, who held high positions in the Mughal court. It is interesting to note that these dialogue participants all held positions of strength and were seekers of power, either religious or political. On the religious dimension of this interaction, the Hindu Goswamis and the Muslim ruler Akbar were well grounded in their own faiths. At the same time, the Goswamis were sure of their religious power, in parallel to the court’s political power. Thus, both these powers engaged in dialogue, leading to a successful outcome.

The result was Emperor Akbar establishing Brindavan as a separate revenue entity and gifting the recreated town, along with generous monetary grants, to the Goswamis. The Goswamis, in their turn, blessed the Mughal emperor. They recognised his greatness not just for these land and monetary grants but for something greater. A 1590 inscription reads:

“When His Highness Akbar ruled over all the world with ease, the virtuous people found total happiness in practising their own faith openly. The faithful Vaisnavas always joyfully blessed him.”

This dialogue reclaimed the lost Brindavan for the Hindus. Moreover, it was like a pebble thrown in the pond, which triggers further ripples. It helped to create an overall peaceful environment, leading to overall development. Historians have named the sixteenth century as India’s golden era, from economic to artistic, intellectual to spiritual creativity. Music, literature, art, architecture, philosophy, trade, and industry reached new heights. Basically it was an era of mutual cooperation and harmony, not just between different ethnic and religious communities, but also when religion and politics could work together for the good of humanity.

Any fruitful interfaith dialogue is based upon respect for the other. For Chaitanya, the other is valuable. He engaged with Buddhism, Islam, and other traditions and integrated various persons and elements from these others. The main category of the metaphysical system advaita (non-dual absolute) seems to be derived from the Buddhist system. The main spiritual practice or ritual for Chaitanya is Nama-Sankirtana (chanting of the divine name), and that has a Buddhist background and flavour. The artistic ritual of sanjhi, the sand paintings in the Chaitanya temples, is a close cousin of Buddhist mandala paintings and Kalachakra ritual. The Islamic tradition trained his three most trusted and respected Goswamis, the Mughal emperor created and gifted Brindavan to Hindus, and, even today, the Muslim community fully participates in the religious life of Brindavan. They build ashrams and temples, decorate deities with dresses and ornaments, craft ritual vessels and thrones for Hindu gods and goddesses. The trade of sacred cows is an enterprise of the Muslim community in Brindavan.

![]()