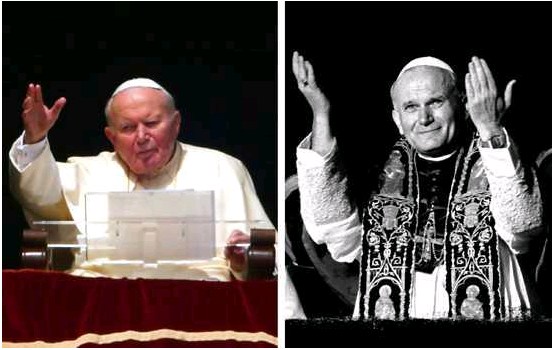

Pope John Paul II was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 to 2005. He was elected pope by the second Papal conclave of 1978, which was called after Pope John Paul I, who had been elected in August to succeed Pope Paul VI, died after 33 days. He was proclaimed Saint on 27 April 2014 by Pope Francis, with Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI in attendance.

Pope John Paul II was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 to 2005. He was elected pope by the second Papal conclave of 1978, which was called after Pope John Paul I, who had been elected in August to succeed Pope Paul VI, died after 33 days. He was proclaimed Saint on 27 April 2014 by Pope Francis, with Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI in attendance.

Pope John Paul II was born Karol Józef Wojtyla (May 18, 1920 in Wadowice, Poland), was chosen Bishop of Rome and head of the Roman Catholic Church on October 16, 1978, becoming the first non-Italian pope in 455 years and the first pope of Slavic origin in the history of the Church.

Pope John Paul II has crusaded against communism, unbridled capitalism and political oppression. He stood firmly against abortion and defended the Church’s traditional approach to human sexuality.

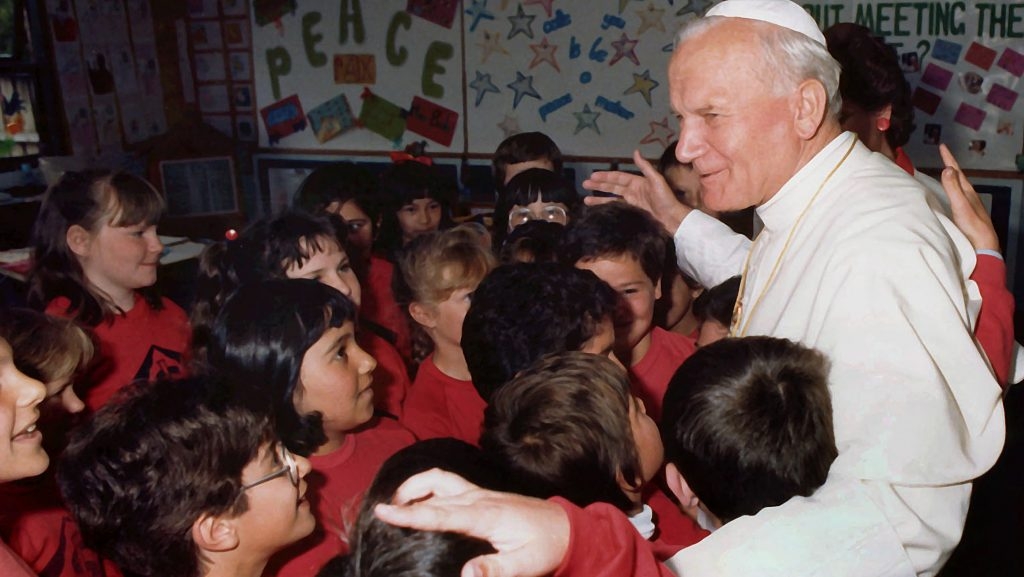

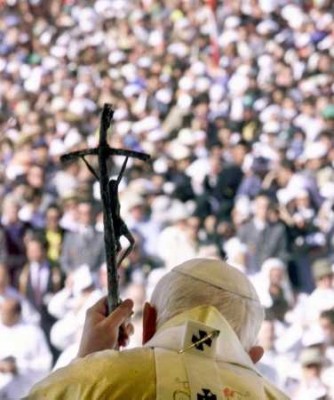

His more than 100 trips abroad have attracted enormous crowds (some of the largest papal crowds ever assembled). With these trips, John Paul II covered a distance far greater than that travelled by all other popes combined. They have been seen as an outward sign of the efforts at global bridge-building between nations and between religions that have been central to his pontificate.

Pope John Paul II beatified and canonised far more persons than any previous pope. John Paul II presided at 147 beatification ceremonies (1,338 Blesseds proclaimed) and 51 canonisation ceremonies (482 Saints) during his pontificate Whether he has canonised more saints than all his predecessors put together, as is sometimes claimed, is difficult to prove, as the records of many early canonisations are incomplete or missing.

On March 14, 2004, his time in office overtook Pope Leo XIII’s as the third-longest pontificate in the history of the Papacy (after Pius IX and St. Peter). The length of his reign is in marked contrast with that of his predecessor Pope John Paul I, who died suddenly after only 33 days in office (and in whose memory John Paul II named himself).

The secular Western world sees John Paul II as a hero, but warms to the singer rather than the song. Yet the song, for those who hear it, is magnificent.

“Open wide the doors for Christ. Do not be afraid. Christ knows ‘what is in man’. He alone knows it.” In Christ is the truth about what it means to be human; to be contrary to Christ is to be contrary to the truth.

Early Life

Karol Joseph Wojtyla was born in Wadowice, Poland on May 18, 1920, the son of Karol and Emilia (Krezorowska) Wojtyla. His father was a former foundry worker and recruiting officer for the Polish Army; his mother was a school teacher.

When he was nine, his mother died and in l932 his brother, fifteen years his senior and an intern, died of scarlet fever contracted from a patient.

After his father’s retirement from active military duty, the family’s modest means forced young Karol to go to work. An athletic boy, Karol swam in the Swaka River and played goalie on the soccer team. As a young boy he enjoyed games and was an excellent student. He served as president of his school student association, but his main extracurricular love was the theatre. Having participated in various school plays, by 1937 Karol starred in and helped direct a school drama club production of Stanislaw Wyspianski’s “Sygmunt August.” On graduating from high school, he decided to study Polish language and literature and to become a professional actor.

After his final examinations in 1937, his father moved with him to Kracow, so he could study at Jagellonian University. On September 1, 1939, he was serving as an altar boy at Mass when bombs began to fall on Kracow.

Around this time, Karol came into contact with Jan Tyranowski (1900-1947), who cultivated Karol’s religious and philosophical interests, bringing him into his informal “Living Rosary” prayer group.

The Nazi occupation forced the University underground and Karol pursued his studies clandestinely while engaged in heavy manual labor as a stone mason to support himself. During this time he was active in the Christian underground movement which helped Jews secure refuge from the Nazis.

By 1942 he was engaged in preliminary studies for the priesthood, hiding with other secret seminarians in the palace of Archbishop Adam Stefan Sapieha while attending classes. He was ordained on November 1, 1946.

Uncle

The Pope was called “Wujek” (Uncle) by his intimates…

Asked to reflect on their formative experiences as young priests, previous popes might have described their years at the Academia, the Roman training school for Vatican diplomats, or their early experiences in a seminary classroom. Pope John Paul II talked about his Srodowisko. This Polish word, which best translates (albeit clumsily) as “milieu”, is used as a self-description by some 200 ordinary men and women with whom Karol Wojtyla has been in intense conversation for decades, in some instances from the first years of his priesthood. For almost a half-century (in some cases), these men and women have called Wojtyla “Wujek” or “Uncle”. Originally a Stalin-era nom de guerre necessitated by the ban imposed by Poland’s Communists on priests working with young people, it remains the name by which Pope John Paul II was known by some of his oldest and closest friends.

That ordinary people were among the intimates of a priest and bishop was a marked contrast to the normal patterns of relations between clergy and laity in the Poland of the 1950s and 1960s. Far more importantly, though, Wojtyla’s Srodowisko had a marked effect on his thinking and teaching. “We were an experimental field for his ideas”, a veteran Srodowisko member recalled . These were the young adults with whom he discussed marital chastity and the Church’s sexual ethic, eventually producing the book “Love and Responsibility”; these were the people whose courtships he counselled, whose marriages he blessed, whose children he baptised, played with, confirmed, and watched grow; these were the men and women who taught him to love human love, as he put it in “Crossing the Threshold of Hope.”

Pope John Paul II remained faithful to the pledge he made when nominated a bishop in 1958: “Wujek will remain Wujek.”

Recognizing Father Wojtyla’s superior intellect, Cardinal Sapieha assigned him to continue his studies at the Angelicum University in Rome, where he received a doctorate in philosophy in 1948. After brief pastoral duties, he earned a second doctorate in theology from the Jagellonian University in Kracow and became successively a professor of theology at the major seminary in Kracow, professor of ethics at the Catholic University of Lublin, and finally chair of the department of philosophy. It was during this period that he emerged as a prolific author of moral and philosophical works, including a play and several poems. In 1959 he was named to the Polish Academy of Sciences for his philosophical writing.

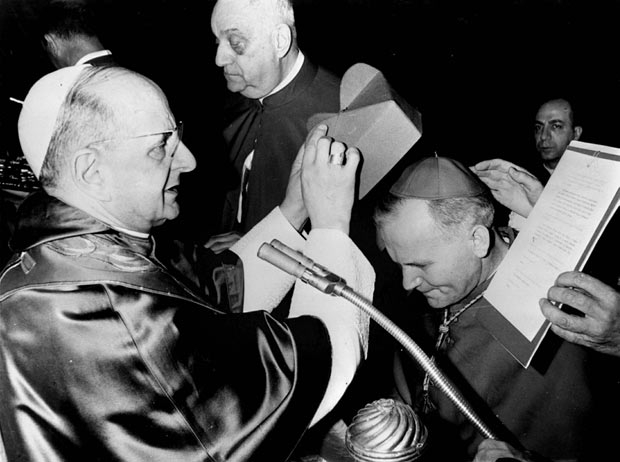

In the summer of 1958, Father Wojtyla was named Auxiliary Bishop of Kracow. In 1964 the civil authorities finally permitted the Church to appoint a resident Archbishop of Kracow for the first time since 1951, he was chosen for the post. Archbishop Wojtyla attended all the sessions of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), where he left his mark on several important documents.

Pope Paul VI, who elevated Archbishop Wojtyla to the College of Cardinals in 1967, recognised his growing stature within the Church and began consulting him on theological matters. Archbishop Wojtyla conducted Pope Paul’s Lenten retreat in 1976, the meditations of which were published in 1979 as “The Sign of Contradiction.” As a Cardinal, Wojtyla visited Asia, North and South America, Europe and Africa.

Al-Qaida

There was a plot to assassinate the Pope during his visit to Manila in January 1995, as part of Operation Bojinka, a mass terrorist attack that was developed by Al-Qaida members Ramzi Yousef and Khalid Sheik Mohammed. A suicide bomber dressed up as a priest, and planned to use the disguise to get closer to the Pope’s motorcade so that he could kill the Pope by detonating himself. Before January 15, the day on which the men were to attack the Pope during his Philippine visit, an apartment fire brought investigators led by Aida Fariscal to Yousef’s laptop computer, which had terrorist plans on it, as well as clothes and items that suggested an assassination plot. Yousef was arrested in Pakistan about a month later, but Khalid Sheik Mohammed was not arrested until 2003.

At the end of the millennium, facing a new cultural revolution, the Catholic Church had become such a complex organisation as to defy any attempt to impose simple authoritarian solutions on it. Rather, that complexity might have seemed sufficient to justify a more ambiguous type of leadership, and to counsel greater flexibility.

But John Paul II did not appear to favour moderation, even in some especially delicate and controversial areas. Thus he refused any liberalisation on birth control, ruling out contraceptive means even in order to check the spread of an AIDS pandemic, and would not admit divorcees to communion in any circumstances, even if they were blameless and in irreversible situations, though many episcopates asked for more openness in these matters. He opposed without exception any institutionalised forms of sexual relationship which differed from the model of Western marriage, refusing to ratify others sacramentally, such as those traditional in Africa and the Far East.

One of the Pope’s main preoccupations has been the mobilisation of the bishops against permissive laws on abortion. The instruction on Respect for Human Life in its Origin (1987) announced that the Roman Church intended to try to get states to reform “morally un-acceptable” civil laws, using the influence of world public opinion and every other means of legal pressure.

In 1995 this position was softened a little when the encyclical Evangelium Vitae appeared. It was ready to allow Catholics in democratic parliaments to support proposals for changing abortion laws so as to limit the damage done by them and lessen their negative effects on culture and public morality, in cases in which it was impossible to revoke the laws or to stop them being approved.

On these matters the Pope did not hesitate to make clear his disagreement with American policy, and his opposition to the platform proposed by the United Nations conference in Cairo on population and development in 1994 and in Beijing on women in 1995. He told an interviewer: “The powers of this world do not always think well of a Pope who acts like this. Sometimes they regard him in a thoroughly bad light, even on questions where moral principles are concerned. They ask for a liberal approach to, for instance, abortion, contraception, divorce. That is what the Pope cannot do, for his task, entrusted to him by God, is to defend the dignity and fundamental rights of the human person, among which the first is the right to life.”

In one field, the Pope took noticeable steps forward – inter-religious dialogue. The day of prayer for peace in Assisi on 27 October 1986, with the participation of representatives of great world religions, is engraved in the religious history of humanity. It stands out like a shining peak, a supreme symbol that the age of the Crusades is past and that force in the service of God is ruled out.

In the same year John Paul II’s visit to the great synagogue in Rome made a huge contribution to dialogue with the Jews, helping the process of overcoming theological anti-Semitism and the “cultural contempt” for Judaism which still has life in it. Once the crisis over the Carmelite convent at Auschwitz had been resolved, and some internal objections overcome, the Pope brushed aside the hesitations of the Secretariat of State and gave his personal approval to the decision to set up diplomatic relations between the Holy See and the State of Israel. Links were duly established in December 1993.

The Pope went even further on 31 October 1997, in his address at a seminar organised by the historical-theological commission for the Jubilee on “the roots of anti-Judaism in Christian circles”. Referring to the wave of anti-Jewish persecution which washed over Europe in the Thirties and Forties, he said that in many cases “the spiritual resistance offered was not what humanity had the right to expect from Christ’s disciples”. He went on: “The time has come to take a clear look at past events so as to purify our memory of them. We must be clear that anti-Semitism has no justification whatsoever and must be absolutely condemned.”

In inter-religious dialogue, not only has John Paul II shown that he respects the conclusions of the Second Vatican Council, but he has taken them further. In the document Dialogue and Proclamation published in 1991, he appealed to “the mystery of the unity of all humanity” as the basis for recognising that the other religious traditions “contain elements of grace” and that “the incipient reality of the kingdom of God can be found beyond the frontiers of the Church, for example in the heart of the faithful of other religious traditions”. In an interview with the Italian journalist Vittorio Messori, published in 1993 and entitled Crossing the Threshold of Hope, the Pope returned to the same theme. All religions have “a common root”, he said, in their concern for salvation.

John Paul II’s approach to the Islamic world is also notable. Addressing the bishops of the Maghreb on a visit to Tunisia on 14 April 1996, he stressed the need to be open to others. Such an attitude, he said, was “in some way a response to God who acknowledges our differences and wants us to know each other more deeply”. He suggested that the different religions at their root “all agree on the acceptance of differences, and on the benefit to be drawn from looking critically at each other and seeing how other people formulate their faith and live it out”. He gave a severe warning that “no one can kill in the name of God, no one can agree to bring death to his own brother”. He urged Catholics in Islamic countries to “go out towards your brothers and sisters without making distinctions on the basis of race or religion”.

“Ut unum sint“, breathed Pope John XXIII as he lay dying, and that same prayer that all may be one became the title of John Paul II’s 1995 encyclical on ecumenism.

In the long sunset of his pontificate, John Paul II, although bowed with age and weakened by the wounds and Parkinson’s Disease, did not give up his journeys to defend the rights of humanity, especially those of the weakest, as well as the truth professed by his Church. When he travelled, he took with him a passport into people’s hearts inscribed with the names of suffering and resistance to evil.

Some Teachings and Confessions of John Paul II

In his homily at his installation as pope, Pope John Paul II encouraged the world not to be afraid of Christ, since Christ alone knows what is in every man. ‘I ask you … I implore you’, he said, ‘allow Christ to speak to man.’

The First Encyclical of John Paul II was Redemptoris Hominis, Man’s Redeemer. It was written in 1979. In the opening of that encyclical, Pope John Paul described his election as Pope, and his very responses to the Cardinal Electors:

It was to Christ the Redeemer that my feelings and my thoughts were directed on 16 October of last year, when, after the canonical election, I was asked: “Do you accept?” I then replied: “With obedience in faith to Christ, my Lord, and with trust in the Mother of Christ and of the Church, in spite of the great difficulties, I accept.”

I chose the same names that were chosen by my beloved Predecessor John Paul I. Indeed, as soon as he announced to the Sacred College on 26 August 1978 that he wished to be called John Paul – such a double name being unprecedented in the history of the Papacy – I saw in it a clear presage of grace for the new pontificate. Since that pontificate lasted barely 33 days, it falls to me not only to continue it but in a certain sense to take it up again at the same starting point. This is confirmed by my choice of these two names. By following the example of my venerable Predecessor in choosing them, I wish like him to express my love for the unique inheritance left to the Church by Popes John XXIII and Paul VI and my personal readiness to develop that inheritance with God’s help.

The Pope went further to write in this encyclical: ~

What Modern Humanity Is Afraid Of

If we read the “signs of the times”

we see that people are afraid of

the result of the work of their hands,

the work of their intellects,

and the tendencies of their wills.

What all this activity yields

is not only simply taken away from them,

but it even turns against them.

Consequently people live increasingly in fear.

They are afraid that part of what they produce

can become the means of an unimaginable self-destruction.

This state of menace shows itself

In various ways.

It shows in the threat to our natural environment.

Yet is was the Creator’s will

that we should communicate with nature

as intelligent and noble guardians

and not as exploiters and destroyers.

The development of moral ethics

seems not to keep in step with the progress of technology

and the development of civilization,

a progress that cannot

fail to give rise to disquiet on many counts.

Does such progress make human life really more human?

Are we really becoming better, more spiritually mature,

more aware of the dignity of humanity, more responsible,

more open to others, especially the neediest and the weakest,

and ready to give and to aid all?

These are questions that must be asked by all.

Are we developing and progressing,

or are we regressing and being degraded?

Does good prevail over evil?

The issue of development is on everybody’s lips,

it fills newspapers all over the world,

but next to all affirmations and certainties,

it is a subject that also contains questions

and anguished disquiet.

The latter are of no less importance

than the former.

John Paul II, in his second encyclical Dives in Misericordiae commenced by saying that God is the Formless Absolute.

“God speaks to humanity by means of the whole universe,

but this perception of God’s power and deity

falls short of a vision of the Father.

“No one has ever seen God;

the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father,

he has made him known”.

Through Christ’s actions and words

…

God becomes known in God’s love for humanity

… In him, God becomes ‘visible’

as the Father ‘who is rich in mercy’.

the present day mentality seems opposed

to a God of Mercy, and in fact to the very idea of mercy.

So John Paul introduces the Encyclical is a oration on the Mercy of God, called Dives in Misericordia, “Richness of Mercy”. Thus, mercy is a facet of the formless absolute.

We read in Sathya Sai Speaks, Volume I, second discourse:

The Lord is a Mountain of Prema; any number of ants carrying away particles of sweetness cannot exhaust His Plenty. He is an Ocean of Mercy without a limiting shore. Bhakthi is the easiest way to win His Grace and also to realise that He pervades everything; in fact, is everything!

In Vidya Vahini, Chapter 11, Sathya Sai Baba wrote:

“Man has to achieve many objects during his life. The highest and the most valuable of these is winning the Mercy of God, the Love of God.”

The Pope went on to say in his introduction to mercy:

“But before we establish the meaning

and the proper content of the concept of mercy,

we must note that Christ, revealing the love-mercy of God,

demanded from people at the same time

that they too should be guided in their lives by love and mercy.

Jesus expressed this by giving the commandment,

which he described as the greatest

in the form of a blessing:

“Blessed are the Merciful,

for they shall obtain mercy”.

Here, the Pope confirms mercy as a sub value of love, and synonymous with love itself.

The Pope then went on to give an exegesis of the richness of the concept of mercy in the Old Testament, and the New. After giving an exegesis on the parable of the Prodigal Son, who goes home to his merciful father, who loves with a selfless love. This selfless love recognises the dignity of the prodigal son, and refuses to allow him to eat the swill of swine and allow him to sleep with the animals outside. John Paul II went on to say:

We sometimes appraise mercy “from the outside”

as a relationship of inequality

between the one offering it

and the one receiving it,

reasoning that mercy belittles the receiver

and offends his or her dignity.

The parable of the prodigal son shows

that the reality is different.

Mercy is based on the common experience

of the dignity that is proper to a person.

….

Mercy does not consist in looking at

moral, physical, material evil.

Mercy restores to value;

it promotes and draws good from evil.

Mercy does not allow itself to be conquered by evil,

but overcomes that evil with good.

Mercy seems particularly necessary for our times.

Finally, John Paul II addresses those who do not share with him the faith and hope of God’s mercy:

And even if there are some who do not share with me

the faith and hope to ask for God’s mercy,

let them at least try to understand my concern.

It is dictated by love for humankind,

according to many contemporaries

threatened by an immense danger

while approaching the end of the millennium.

We pray that the love of the Father

may once again be revealed to the world

through the work of the Son and the Holy Spirit.

“Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.”

Sathya Sai Baba wrote in Prema Vahini, page 75,

One’s selfish needs have to be sacrificed. There must be constant efforts to do good to others. One’s desire should be to establish the welfare of the world. With all these feelings filling the heart, one must meditate on the Lord. THIS is the right path. If ‘great men’ and those in authority are thus engaged in the service of humanity, and in promoting the welfare of the world, the thieves of passion, hatred, pride, envy, jealousy and conceit will not invade the minds of men; the divine possessions of man, like dharma, mercy, truth, love, knowledge and wisdom will be safe from harm.

Thus it may be gleaned from the above that Pope John Paul II was a protector and promoter of Divine Mercy in the modern world.

Passing of John Paul II

On 31 March 2005, following a urinary tract infection, he developed septic shock, a form of infection with a high fever and low blood pressure, but was not hospitalised. Instead, he was monitored by a team of consultants at his private residence. This was taken as an indication by the pope, and those close to him, that he was nearing death; it would have been in accordance with his wishes to die in the Vatican.

On Saturday, 2 April 2005, at approximately 15:30 CEST, John Paul II spoke his final words in Polish, “Pozwólcie mi odejść do domu Ojca” (“Allow me to depart to the house of the Father”), to his aides, and fell into a coma about four hours later. Pope John Paul II died in his private apartment at 21:37 that evening.

Inspired by calls of “Santo Subito!” (“[Make him a] Saint Immediately!”) from the crowds gathered during the funeral Mass that he performed, Pope Benedict XVI began the beatification process for his predecessor, bypassing the normal restriction that five years must pass after a person’s death before beginning the beatification process.

On 4 July 2013, Pope Francis confirmed his approval of John Paul II’s canonisation, formally recognising the second miracle attributed to his intercession. He was canonised together with Pope John XXIII. The date of the canonisation was on 27 April 2014, Divine Mercy Sunday.

this page originally appeared on Saieditor.com and was last updated 29/12/2018

![]()