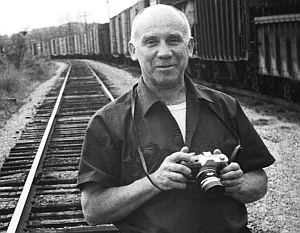

Thomas Merton OCSO was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist, and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the priesthood and given the name Father Louis. His autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain has inspired millions to seek the interior life.

Thomas Merton OCSO was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist, and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the priesthood and given the name Father Louis. His autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain has inspired millions to seek the interior life.

Thomas Merton, o.c.s.o.

(Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance)

1915 – 1968

(Prayer of Thomas Merton)

My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going.

I do not see the road ahead of me.

I cannot know for certain where it will end.

Nor do I really know myself,

and the fact that I think that I am following your will

does not mean that I am actually doing so.

But I believe that the desire to please you

does in fact please you.

And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing.

I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire.

And I know that if I do this

you will lead me by the right road

though I may know nothing about it.

Therefore will I trust you always

though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death.

I will not fear, for you are ever with me,

and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.

(from “Thoughts in Solitude” © Abbey of Gethsemani.)

Thomas Merton was born on 31 January 1915 at Prades, France. He had a difficult and often unhappy childhood. His mother, Ruth, died when he was six. His father, Owen, an artist, moved him from place to place, often left him alone as he pursued his art, and died when Merton was fifteen. Through his teens and early twenties Merton led a sensual, confused, but searching life. In his mid-twenties he experienced a religious conversion, joining the Catholic Church while a student at Columbia University. He entered Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky at the age of twenty-six and continued the search as a Trappist monk until his death on 10 December 1968 at the age of fifty- three.

A Trappist Monk in the Enclosure

The Trappists, officially the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, are a Catholic religious order of cloistered monastics that branched off from the Cistercians.

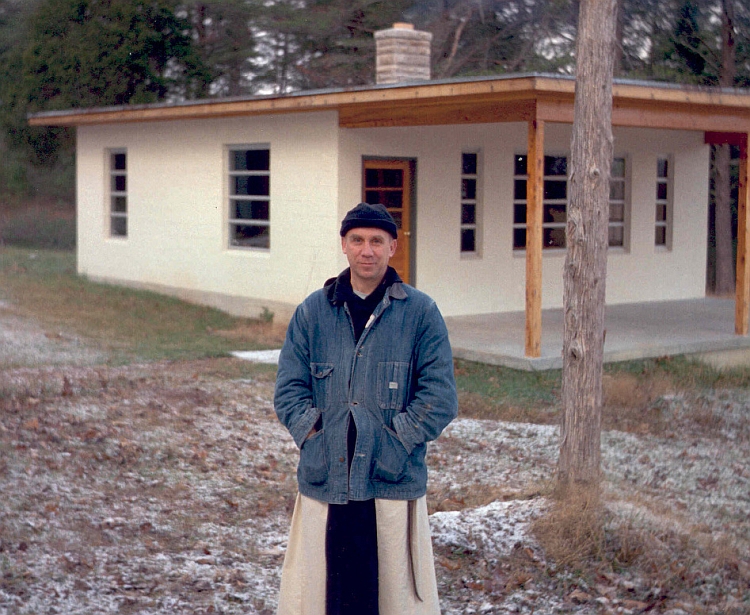

Gethsemani Abbey is an abbey of the Cistercian Monks in the Catholic Church. Cistercian Monks are enclosed and generally do not interact with the wider community; the meaning of enclosure being to generate an environment conducive to interior silence. Cistercians, like many other monastic orders, observe the “Hours” of the Church in prayer, praying in community and engaging in monastic choir to sing to the glory of God.

Here, Merton speaks on the solitude of the Monastic life:

March 8, 1966

Merton in fact did not ‘publish’. He had to submit all his writings to the ‘censors’ in the Monastic order who read the material in order to see that it complied with the teachings of the Catholic Church, and it did not give ‘scandal’ to the Christian community. After the censors had done their excuplatory task, Merton would turn the manuscript over to one of his friends who would submit to publishers. While Merton himself recognised that a considerable part of his writing was not good, his best writing rings with spiritual authenticity. He brought to life for generations of ordinary people the vocabulary of monastic devotion, the language of presence, compassion, purity of heart, solitude and love in a new and fresh fashion.

The range and depth of Merton’s search is indicated by the diverse categories into which his writings fall. There are personal journals (e.g., The Sign of Jonas), devotional mediations (e.g., New Seeds of Contemplation), theological essays (e.g., The Ascent to Truth), social criticism and commentary (e.g., Seeds of Destruction), explorations in Eastern spirituality (e.g., Zen and the Birds of Appetite), biblical studies (e.g., Bread in the Wilderness), poetry (e.g. Emblems of a Season of Fury), and collections of essays and reviews (e.g. Raids on the Unspeakable). The general movement of Merton’s writing over the years reflects his own spiritual growth – from the enthusiastic but constricted Catholicism of the young convert, to the radical openness of the mature Merton, reaching out to other spiritual traditions and to the world beyond the monastery walls.

No matter how widely Merton reached in his spiritual search, he remained grounded in the personal experience of God in Christ. For Merton, the spiritual search is deeply inwards, towards the Christ in each of us who is also our True Self. We meet this Christ in solitude and contemplation. But such a life is not the special prerogative of the monk; every Christian is called to it. It was Merton’s genius to articulate monastic spirituality for people ‘in the world’, and to remind monks that they are in the world too. Merton’s life and thought spoke powerfully to many precisely because he overcame false and crippling separations between self and God, church and world, prayer and politics.

Enclosed Monks not at any remove

Merton’s early love affair with traditional monastic life is reflected also in The Sign of Jonas – a monasticism characterised by the round of daily prayer, work, silence and biblical meditation. All this took a quite new turn when, as he famously described it in his book Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, he was in downtown Louisville and realised, with the force of an epiphany, that he loved and identified with all the people going about their business and, further, that he and all monks were in community with them. “It was”, he wrote, “like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world, the world of renunciation and supposed holiness. The whole illusion of a separate holy existence is a dream. … To think that for 16 or 17 years I have been taking seriously this pure illusion that is implicit in so much of our monastic thinking.” He continued:

“I have the immense joy of being man, a member of a race which God himself became incarnate. … If only everybody could realise this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.” If we could all see ourselves as we really are, he reflected, “there would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed …”

That intuition of solidarity more than justified Merton’s plan to form networks of friendship with persons who were authentic searchers for truth and justice. From his adamantine conviction that precisely as a contemplative monk he could contribute to that search comes his vast exchange of letters with Latin American poets and intellectuals, peace activists, as well as a wide range of Protestant, Jewish, Muslim and Buddhist writers. In the last decade of his life, his study of Asian religions intensified, culminating in his fateful journey to Asia where he met his death by accidental electrocution on the 10th of December 1968.

A Plethora of Divinity

One finds in his informal conferences, in his essays and journal entries, lapidary observations, rooted in his own experience of prayer, about the reality of God in life. Listen to Merton speaking to young monks:

Life is very simple: we are living in a world that is absolutely transparent to God and God is shining through it all the time. This is not a fable or a nice story. It is true. God manifests himself everywhere, in every thing, in people and in things and in nature and in events. You cannot be without God. It’s impossible. Simply impossible.

In certain respects, no monk lives for himself alone. The vulnerability to experience, the predisposition to prayer and meditation, the habtiation of manual labour and contemplation are gifts that have add on value to each and every other human life. The sensitivity and clarity of vision, the joys and failures of the monk awaken the capacity within ourselves to see the world as divine, to reflect, to wonder, to view creation as the creator surely views it:

February 17, 1966

Today was the prophetic day, the first of the real shining spring – not that there was not warm weather last week, or that there will not be cold weather again, but this was the day of the year when spring became truly credible. Freezing night but cold, bright morning and a brave, bright shining of the sun that is new and an awakening in all the land, as if the earth were aware of its capacities!

I saw the woodchuck had opened up his den and had come out, after three months or so of sleep, and at that early hour it was still freezing: I thought he had gone crazy. The day proved him right and me wrong.

The morning got more and more brilliant, and I could feel the brilliancy of it getting into my own blood. Living so close to the cold, you feel the spring. This is man’s mission! The earth cannot feel all this. We must. Living away from the earth and the trees, we fail them. We are absent from the wedding feast.

There are moments of great loneliness and lostness in solitude, but often there come other deeper moments of hope and understanding, and I realize that these would not be possible in their purity, their simple secret directions, anywhere but in solitude. I hope to be worthy of them!

After dinner, when I came back to the hermitage, the whole hillside was so bright and new I wanted to cry out. I got tears in my eyes from it!

With the new comes also memory, as if that which was once so fresh in the past (days of discovery when I was 19 or 20) were very close again, as if one were beginning to live again from the beginning: one must experience spring like that. A whole new chance! A complete renewal!

Discovering Eastern Religions

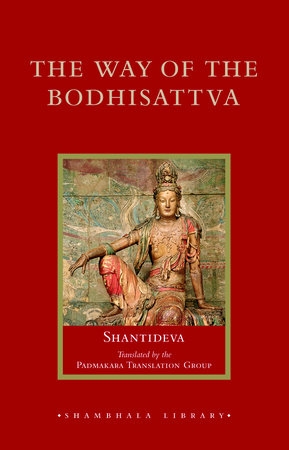

Merton studied other religions and other guides to the spiritual life. In his journal entry for June 29, 1968, Thomas Merton comments on his reading of the eighth-century Buddhist scholar Shantideva whose writing described the inner work necessary to become a Bodhisattva:

“I am spending the afternoon reading Shantideva, in the woods near [my] hermitage — the oak grove to the southwest — a cool, breezy spot on a hot afternoon. Thinking deeply of Shantideva and my own need of discipline. What a fool I have been, in the literal and biblical sense of the word: thoughtless, impulsive, lazy, self-interested yet alien to myself, untrue to myself, following the most stupid fantasies, guided by the most idiotic emotions and needs. Yes [being human] I know, it is partly unavoidable. But I know too that in spite of all contradictions there is a center and a strength to which I always have access if I really desire it. The grace to desire it is surely there.

Merton went on to write that it would do no good to anyone if he just went around talking — no matter how articulate — in this condition. “There is still so much to learn, so much deepening to be done, so much to surrender. My real business is something far different from simply giving out words and ideas and ‘doing things’ – even to help others. The best thing I can give to others is to liberate myself from the common delusions and be, for myself and for [others], free. Then grace can work in and through me for everyone.”

“What impresses me most – reading Shantideva — is not only the emphasis on solitude but [his] idea of solitude as part of the clarification [necessary for] living for others: [the] dissolution of the self in “belonging to everyone” and regarding everyone’s suffering as one’s own. This is really incomprehensible unless one shares something of the deep, existential Buddhist concept of suffering as bound up with the arbitrary formation of an illusory ego-self. To be “homeless” is to abandon one’s attachment to a particular ego—and yet to care for one’s own life (in the highest sense) in the service of others.”

A deep and beautiful idea [in Shantideva when he writes:] “Be jealous of your self and afraid when you see your self is at ease and your sister is in distress, that your self is in high estate and your sister is brought low, that you are at rest and your sister labours. Make your self lose its pleasures and bear the sorrow of your fellow human beings.” [The End of the Journey. Journals Vol. 8., pp. 135]

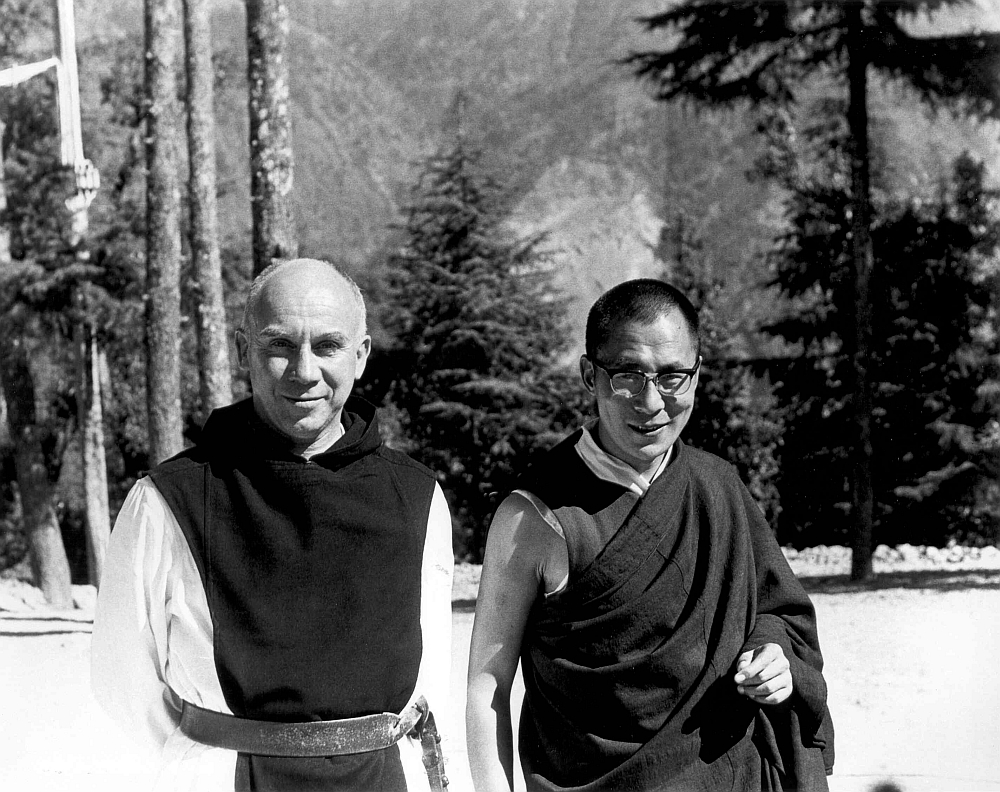

Meets Dalai Lama

Thomas Merton has become an icon to modern spiritual seekers. He courageously dialogued with monks of other faiths and discoursed with them on being a monk and the pursuit of the spiritual life. He met the Dalai Llama in Dharamsala and had several memorable conversations… the following is from The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton.

Harold Talbott writes that the Dalai Lama has to see a lot of blue-haired ladies in eccentric clothing. And people looking for a freak religion. And rich people who have nothing better to do than come up here out of curiosity. His Western visitors are not well screened. He has very few real advisers who know anything about the world as it is. The Dalai Lama is still studying under his tutor and also is going on with Tantric studies, and I was told by Tenzin Geshe, his secretary, that he enjoys his new house, where he has quieter quarters, is less disturbed, and has a garden to walk in now, without being followed around by cops. The Dalai Lama is loved by his people – and they are a beautiful, loving people. They surround his house with love and prayer, they have a new soongkhor for protection along the fence. Probably no leader in the world is so much loved by his followers and means so much to them. He means everything to them. For that reason it would be especially terrible and cruel if any evil should strike him. I pray for his safety and fear for him. May God protect and preserve him.

Experience of Dharamsala

Merton wrote descriptively about his experiences at Dharamsala, the refuge of Tibetans in Exile.

7pm: Tenzin Geshe, the very young secretary of the Dalai Lama, has just left. He came down to tell us of plans for my audience tomorrow at 10am. A young, intelligent, eager guy. He seems to be only in his twenties, and the Dalai Lama himself is only thirty-three. He brought me the first copy of a mimeographed newspaper that is being put out here for Tibetans. There are great problems for the Tibetan refugees like those I saw today in Upper Dharamsala living in many tents under the trees on the steep mountainside, clinging precariously to a world in which they have no place and only waiting to be moved somewhere else – to “camps.” We had walked up, Harold and I, to Upper Dharamsala by the back road to McLeod Ganj, which is where the Dalai Lama lives. It is really the top of the mountain we are on now. Suddenly we were in a Tibetan village with a new, spanking white chorten in the middle of it. There we met Sonam Kazi, who was expecting us to come by bus. We climbed higher to the empty buildings of Swarg Ashram which the Dalai Lama has just vacated to move to his new quarters. A lovely site, but cramped. The buildings are old and ramshackle, and as Sonam said, “the roof leaks like hell.” Then further on up to the top – an empty house surrounded by prayer flags. Tibetans are established all over the mountain in huts, houses, tents, anything. Prayer flags flutter among the trees. Rock mandalas are along all the pathways. Om Mane Padme Hum, the Tibetan mantra (meaning The Jewel in the Lotus) is carved on every boulder. It is moving to see so many Tibetans going about silently praying — almost all of them are constantly carrying rosaries. We visited a small monastic community of lamas under the Dalai Lama’s private chaplain, the Khempo of Namgyal Tra-Tsang, whom I met. We were ushered into his room where he sat studying Tibetan block-print texts in narrow oblong sheets. He was wearing tinted glasses. The usual rows of little bowls of water. A tanka. Marigolds growing in old tin cans.

November 4, 1968 / Afternoon

I had my audience with the Dalai Lama this morning in his new quarters. It was a bright, sunny day – blue sky, the mountains absolutely clear. Tenzin Geshe sent a jeep down. We went up the long way round through the army post and past the old deserted Anglican Church of St. John in the Wilderness. Everything at McLeod Ganj is admirably situated, high over the valley, with snow-covered mountains behind, all pine trees, with apes in them, and a vast view over the plains to the south. Our passports were inspected by an Indian official at the gate of the Dalai Lama’s place. There were several monks standing around — like monks standing around anywhere — perhaps waiting to go somewhere. A brief wait in a sitting room, all spanking new, a lively, bright Tibetan carpet, bookshelves full of the Kangyur and Tangyur scriptures presented to the Dalai Lama by Suzuki.

The Dalai Lama is most impressive as a person. He is strong and alert, bigger than I expected (for some reason I thought he would be small). A very solid, energetic, generous, and warm person, very capably trying to handle enormous problems — none of which he mentioned directly. There was not a word of politics. The whole conversation was about religion and philosophy and especially ways of meditation. He said he was glad to see me, had heard a lot about me. I talked mostly of my own personal concerns, my interest in Tibetan mysticism. Some of what he replied was confidential and frank. In general he advised me to get a good base in Madhyamika philosophy (Nagarjuna and other authentic Indian sources) and to consult qualified Tibetan scholars, uniting study and practice. Dzogchen was good, he said, provided one had a sufficient grounding in metaphysics or anyway Madhyamika, which is beyond metaphysics. One gets the impression that he is very sensitive about partial and distorted Western views of Tibetan mysticism and especially about popular myths. He himself offered to give me another audience the day after tomorrow and said he had some questions he wanted to ask me.

The Dalai Lama is also sensitive about the views of other Buddhists concerning Tibetan Buddhism, especially some Theravadan Buddhists who accuse Tibetan Buddhism of corruption by non-Buddhist elements. The Dalai Lama told me that Sonam Kazi knew all about Dzogchen and could help me, which of course he already has.

It is important, the Dalai Lama said, not to misunderstand the simplicity of Dzogchen, or to imagine it is “easy,” or that one can evade the difficulties of the ascent by taking this “direct path.” He recommended Geshe Sopa of the New Jersey monastery who has been teaching at the University of Wisconsin, and Geshe Ugyen Tseten of Rikon, Switzerland.

November 8, 1968

My third interview with the Dalai Lama was in some ways the best. He asked a lot of questions about Western monastic life, particularly the vows, the rule of silence, the ascetic way, etc. But what concerned him most was:

Did the “vows” have any connection with a spiritual transmission or initiation?

Having made vows, did the monks continue to progress along a spiritual way, toward an eventual illumination, and what were the degrees of that progress? And supposing a monk died without having attained to perfect illumination? What ascetic methods were used to help purify the mind of passions?

He was interested in the “mystical life,” rather than in external observance.

And some incidental questions:

What were the motives for the monks not eating meat? Did they drink alcoholic beverages? Did they have movies? And so on …

The End of the Journey

Merton went on to Calcutta, to Bangkok, to give his paper to the World Conference on the renewal of Monasticism. On the morning of 10 December, he presented his paper, and all present retired for a siesta, to return later to ask questions and discuss Merton’s ideas. Merton took a shower, and was accidentally electrocuted. He passed away at 2pm on 10th of December, 1968. His Abbot was contacted, who in turn contacted the US diplomatic staff who arranged for the body to be flown home by the US Army. Merton was buried in a simple monks grave at his Kentucky home, the Cistercian Abbey of Gethsemani.

Thomas Merton open many doors, both in ecclesiastical and everyday environments, and made the reailtiy of the hermitage, the spiritual life and the capacity to pursue the interior silence available to the daily breadwinner, the housewife, the businessman, the enquiring young adults seeking meaning in life. He was a pioneer in the nascent interfaith field, discussing monasticism with monks from other religious traditions when his life came to closure. Merton is studied by many, world-wide for his simplicity in expressing the spiritual life amid the manifold distractions of the day-by-day expressions of divinity-in-ordinary. He opened the possibility of experience of the divine up to millions.

this page originally appeared on Saieditor.com and was last updated 30/12/2018

![]()