Prokhor Isidorovitch Moshnin, who later took the name Seraphim, was born in central Russia into a trading family. In his youth his father died and at the age of 15, Seraphim went to the famous monastery of Caves at Kiev, later entering the Sarov monastery in the Oka region as a novice. He was ordained a monk in 1786 and a priest in 1793. The following year he built himself a little hermitage in the forest where he spent ten years in the most austere conditions, feeding wild animals by hand. He was left crippled after a savage attack by robbers.

Prokhor Isidorovitch Moshnin, who later took the name Seraphim, was born in central Russia into a trading family. In his youth his father died and at the age of 15, Seraphim went to the famous monastery of Caves at Kiev, later entering the Sarov monastery in the Oka region as a novice. He was ordained a monk in 1786 and a priest in 1793. The following year he built himself a little hermitage in the forest where he spent ten years in the most austere conditions, feeding wild animals by hand. He was left crippled after a savage attack by robbers.

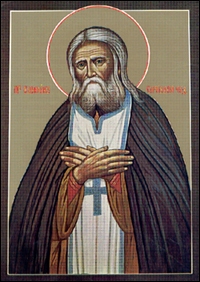

Holy Saint and Starets of the Russian Orthodox Church

The Holy Land of Russia

Dostoevsky affirmed that the Russian people ‘recognizes sanctity as the highest value’, and formal canonisation in the Russian Church confirms popular veneration, Russian spirituality is especially illuminated in its saints. Saint Vladimir, Prince of Kiev (980-1015) and converter of Russia to Christianity, instituted an emphasis on the social, corporate implications of Christianity. The first Russian saints to be canonised were his sons. Saint Boris and the childlike Saint Gleb, who were political victims, killed in 1015 by their brother, but not martyrs for their faith. Their sanctity was popularly perceived in their voluntary participation in Christ’s passion, an intuition, through suffering, of the emptied-out, humiliated Christ. Subsequently the Russian church has especially loved and venerated a tradition of gentle sufferers, a feeling complemented by the power of belief in the resurrection and its universal application (the Russian word for Sunday is resurrection). A sense of the complete incarnation of the spiritual in the material is a fundamental theme in Russian spirituality; it is implicit in the Russian peasant’s feeling for the earth, Holy Russia, and in the sense of divine presence in the icons, crosses and other holy objects that are kissed and worshipped in the Russian church. Pope St John Paul II wrote an encyclical shortly after his election, ‘The Holy Land of Rus‘, thus confirming this valuable tradition.

The Holy Icons

To look at an icon is to enter into the reality portrayed by the icon. Hence the Russian (and other orthodox communions) use of Icons. The saints and martyrs are in heaven with Almighty God, and Jesus Christ, and the Virgin Mary. As one gazes at an icon, one leaves the earthly realm and enters the sacred. The Orthodox liturgical calendar is full of the names of martyrs and confessors for icons. The Russian preference for the Vladimir icon of the Mother of God, known as Umilenie (tenderness), rather than the Odigitriya (queen type), strikes a deep chord in Russian spirituality: the Russians especially love and venerate the Mother of God as Mother, the one human being who achieved an ideal harmony of spirit and body to become the genuine, free partner of the Creator. It is the Virgin Mary who appears as the Divine to St Seraphim of Sarov.

Son of a Trader

To find St Seraphim we have to leave behind the urban, cosmopolitan world of Marxist-Lenist Russia and wend our way into the forests of southern Russia, into a monastic culture fed by constant reading from the Bible and the lives of the early saints. For Seraphim the world of the early monks and hermits provided models of sanctity for every age. He himself imitated St Antony of Egypt by spending decades in strict seclusion, with virgin forest as his equivalent of the desert; for 1,000 nights and days he imitated St Symeon the Stylite by standing and praying on a rock. Just as St Anthony eventually came out of seclusion to act as a spiritual father, so Seraphim in the last eight years of his life opened the doors of his cell to whoever wished to consult him.

Prokhor Isidorovitch Moshnin, who later took the name Seraphim, was born in central Russia into a trading family. In his youth his father died and at the age of 15, Seraphim went to the famous monastery of Caves at Kiev, later entering the Sarov monastery in the Oka region as a novice. He was ordained a monk in 1786 and a priest in 1793. The following year he built himself a little hermitage in the forest where he spent ten years in the most austere conditions, feeding wild animals by hand. He was left crippled after a savage attack by robbers.

Conversation of St. Seraphim with N. A. Motovilov about his life:

Now I will tell you about myself, poor Seraphim. I come of a merchant family in Kursk. So when I was not yet in the Monastery we used to trade with the goods which brought us the greatest profit. Act like that, my son. And just as in business the main point is not merely to trade, but to get as much profit as possible, so in the business of the Christian life the main point is not merely to pray or to do some other good deed. Though the Apostle says: Pray without ceasing (I Thess. 5:17), yet, as you remember, he adds: I would rather speak five words with my understanding than ten thousand words with the tongue (I Cor. 14:13). And the Lord says: Not everyone that says unto Me: Lord, Lord, shall be saved, but he who does the will of My Father, that is he who does the work of God and, moreover, does it with reverence, for cursed is he who does the work of God negligently (Jer. 48:10). And the work of God is: Believe in God and in Him Whom He has sent, Jesus Christ (Jn. 14:1;6:29). If we understand the commandments of Christ and of the Apostles aright, our business as Christians consists not in increasing the number of our good deeds which are only the means of furthering the purpose of our Christian life, but in deriving from them the utmost profit, that is in acquiring the most abundant gifts of the Holy Spirit.

St. Seraphim revives the tradition of Starets

On his return to the monastery, Seraphim lived in absolute seclusion until the day – 25 November 1825 – when an apparition of the Virgin ordered him to receive pilgrims. Thus his life as a starets began. He dispensed his knowledge and teaching to the countless pilgrims who came looking for him and founded several monasteries for penitents of both sexes at Dievo. Blindly embracing the biblical renunciation of worldly possessions can lead, however, to strannichestvo, the tradition of wandering; this too is a characteristic tendency in Russian spirituality, and in the nineteenth century The Way of a Pilgrim, a book which describes the wandering life of a peasant who practised the Jesus prayer under the guidance of a starets, achieved a great popular following.

Dostoevsky images a Starets

A Starets is a spiritual father. In another tradition, the starets might be called the Guru or even the spirit guide. Like the Gu-ru (one who removes the darkness) a starets has trod the spiritual path and attained divinity. In traditional monastic Russian life, the starets (plural startsy) is the spiritual master who initiates the young novice. In the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the startsy, often venerable old men, became, the spiritual directors of the Russian spiritual elite. The most famous were those of the monastery of Optino in the province of Kaluga, in The Brothers Karamazov. Dostoevsky gives a portrait of the starets Zossima. The writer seems to have borrowed features from several famous startsy.

“What, then, is a starets? A starets is a man who takes your soul and your will into his soul and will. Having chosen your starets, you renounce your will and yield it to him in complete submission and complete self-abnegation.

Ordinary people as well as great aristocrats flocked to the startsy of our monastery, so that, prostrating themselves before them, they could confess their doubts, their sins and their sufferings, and ask for counsel and admonition.

It was said by many people about the Elder Zossima that, by permitting everyone for so many years to come and bare their hearts and beg his advice and healing words he had absorbed so many secrets, sorrows and avowals into his soul that in the end he acquired so fine a perception that he could tell at the first glance from the face of a stranger what he came for, what he wanted, and what kind of torment racked his conscience. Indeed he sometimes astounded, confounded and almost frighten his visitor by this knowledge of his secret before he even had time to utter a word…

Many, almost all, who went for the first time to have a private talk with the elder, entered his cell in fear and trepidation, but almost always came out looking bright and happy, and even the gloomiest face was transformed into a happy one”

Visiting St Seraphim

Visitors made the long journey in prodigious numbers: there could be up to 2,000 of them waiting round his cell. They flocked to him for the same reason that comparable numbers had gone to see St. Symeon Stylites a millennium and a half before: they saw in him a man of authority whose years as a recluse made him a privileged visitor from another world, qualified to speak as the mouthpiece of God’s love for each individual. What guidance did Seraphim offer his visitors? As a priest he regularly absolved them from their sins without demanding a detailed confession. His confidence in the power of divine grace led him to affirm that all those united to the Christ through the Eucharist would be saved; he taught strict observance of the rules of the Church, but refused to turn this into a condition for salvation.

The severe asceticism that he himself practised shows that he did not water down the demands of the faith; but he had a vivid sense of the Church as the communion of saints living and dead, whose self-sacrifice atoned for the failings of others. His favourite theme was joy – the joy that radiates from our sense of the power of Christ present to heal and gave. His customary greeting to everyone who came to him was, “You my joy, Christ is risen“.

Conversation of St. Seraphim with N. A. Motovilov

[Motovilov is visiting the Saint].

It was Thursday. The day was gloomy. The snow lay eight inches deep on the ground; and dry, crisp snowflakes were falling thickly from the sky when Father Seraphim began his conversation with me in a field adjoining his near hermitage, opposite the River Sarovka, at the foot of the hill which slopes down to the river bank. He sat me on the stump of a tree which he had just felled, and he himself squatted opposite me.

“The Lord has revealed to me,” said the great Elder, “that in your childhood you had a great desire to know the aim of our Christian life, and that you continually asked many great spiritual persons about it.”

I must say here that from the age of twelve this thought had constantly troubled me. I had, in fact, approached many clergy about it; but their answers had not satisfied me. This was not known to the Elder.

“But no one,” continued Father Seraphim, “has given you a precise answer. They have said to you: ‘Go to Church, pray to God, do the commandments of God, do good — that is the aim of the Christian life.’ Some were even indignant with you for being occupied with profane curiosity and said to you: ‘Do not seek things that are beyond you.’ But they did not speak as they should. And now poor Seraphim will explain to you in what this aim really consists.

St Seraphim advises on Karma Yoga, and Nishkama kama

One may do a charitable deed for his or her brother or sister may be in dire need of assistance. One may do a charitable deed to acquire gifts in heaven [grace and blessings] for oneself. One may do a deed because the laws of the Church specify this is good for your soul [like fasting in Lent]. The principle of surrender is often painted with the image of not letting the left hand knowing what the right hand is doing. However, such acts must be done for the sake of the Lord and left to the outcome of the Lord.

“Prayer, fasting, vigil and all other Christian activities, however good they may be in themselves, do not constitute the aim of our Christian life, although they serve as the indispensable means of reaching this end. The true aim of our Christian life consists in the acquisition of the Holy Spirit of God. As for fasts, and vigils, and prayer, and almsgiving, and every good deed done for Christ’s sake, they are only means of acquiring the Holy Spirit of God. But mark, my son, only the good deed done for Christ’s sake brings us the fruits of the Holy Spirit. All that is not done for Christ’s sake, even though it be good, brings neither reward in the future life nor the grace of God in this. That is why our Lord Jesus Christ said: He who gathers not with Me scatters (Luke 11:23). Not that a good deed can be called anything but gathering, since even though it is not done for Christ’s sake, yet it is good. Scripture says: In every nation he who fears God and works righteousness is acceptable to Him (Acts 10:35).

Secular Imagery for Spiritual Progress

The famous dictum, ‘Work is worship, duty is God“, is illumined most powerfully by St Seraphim. Using the ordinary metaphor of acquiring goods and services, he takes this further into the realm of spiritual progress:

“Acquiring is the same as obtaining,” he replied. “You understand, of course, what acquiring money means? Acquiring the Spirit of God is exactly the same. You know well enough what it means in a worldly sense, your Godliness, to acquire. The aim in life of ordinary worldly people is to acquire or make money, and for the nobility it is in addition to receive honours, distinctions and other rewards for their services to the government. The acquisition of God’s Spirit is also capital, but grace-giving and eternal, and it is obtained in very similar ways, almost the same ways as monetary, social and temporal capital.

Grace and gifts should be given away to others.

Any gift given to another in the name of the Lord is naturally surrendered unto the Lord. St Seraphim hints at selfless service to others and hints at the grace of the Lord flowing through service:

“That’s it, my son. That is how you must spiritually trade in virtue. Distribute the Holy Spirit’s gifts of grace to those in need of them, just as a lighted candle burning with earthly fire shines itself and lights other candles for the illumining of all in other places, without diminishing its own light. And if it is so with regard to earthly fire, what shall we say about the fire of the grace of the All-Holy Spirit of God? For earthly riches decrease with distribution, but the more the heavenly riches of God’s grace are distributed, the more they increase in him who distributes them. Thus the Lord Himself was pleased to say to the Samaritan woman: Whoever drinks of this water will thirst again. But whoever drinks of the water that I shall give him will never thirst; but the water that I shall give him will be in him a well of water springing up into eternal life (Jn. 4:13-14).

Canonisation and Cult

Seraphim’s canonisation in 1903 was forced on a reluctant church hierarchy by popular demand. Seraphim became associated with a body of dubious prophecies, some of them anti-Semitic, and including a supposed assurance that the latter part of Tsar Nicholas II’s reign would be long and glorious. It is to the credit of the hierarchy of the Russian Orthodox Church that it discouraged the circulation of these prophecies, which have never played and part in the popular cult of the saint. The canonisation was accompanied by the publication of the Conversation with Motovilov, in which Seraphim reveals at length his teaching on the gifts of the Holy Spirit, leading up to the extraordinary climax where Motovilov sees Seraphim’s face shining with a heavenly light, like that of Christ on the Mount of Tabor. The work had been ‘discovered’ by an unscrupulous propagandist who was simultaneously engaged in the publication of the most notorious of all literary forgeries, the Protocols of the Elders of Sion. Since then, the ‘Conversation‘ has become accepted as one of the classics of Russian spirituality.

Palm Sunday at St Seraphim of Sarov Church, Richmond Hill. Icons are of the Virgin Mary, Christ with the Gospels, and St Seraphim.

The Transfiguration of St Seraphim

(Fr Seraphim is addressing Motilovov ‘your Godliness’)

“Nevertheless,” I replied, “I do not understand how I can be certain that I am in the Spirit of God. How can I discern for myself His true manifestation in me?”

Father Seraphim replied: “I have already told you, your Godliness, that it is very simple and I have related in detail how people come to be in the Spirit of God and how we can recognize His presence in us. So what do you want, my son?”

“I want to understand it well,” I said.

Then Father Seraphim took me very firmly by the shoulders and said: “We are both in the Spirit of God now, my son. Why don’t you look at me?”

I replied: “I cannot look, Father, because your eyes are flashing like lightning. Your face has become brighter than the sun, and my eyes ache with pain.”

Father Seraphim said: “Don’t be alarmed, your Godliness! Now you yourself have become as bright as I am. You are now in the fullness of the Spirit of God yourself; otherwise you would not be able to see me as I am.”

Then, bending his head towards me, he whispered softly in my ear: “Thank the Lord God for His unutterable mercy to us! You saw that I did not even cross myself; and only in my heart I prayed mentally to the Lord God and said within myself: ‘Lord, grant him to see clearly with his bodily eyes that descent of Thy Spirit which Thou grantest to Thy servants when Thou art pleased to appear in the light of Thy magnificent glory.’ And you see, my son, the Lord instantly fulfilled the humble prayer of poor Seraphim. How then shall we not thank Him for this unspeakable gift to us both? Even to the greatest hermits, my son, the Lord God does not always show His mercy in this way. This grace of God, like a loving mother, has been pleased to comfort your contrite heart at the intercession of the Mother of God herself. But why, my son, do you not look me in the eyes? Just look, and don’t be afraid! The Lord is with us!”

After these words I glanced at his face and there came over me an even greater reverent awe. Imagine in the center of the sun, in the dazzling light of its midday rays, the face of a man talking to you. You see the movement of his lips and the changing expression of his eyes, you hear his voice, you feel someone holding your shoulders; yet you do not see his hands, you do not even see yourself or his figure, but only a blinding light spreading far around for several yards and illumining with its glaring sheen both the snow-blanket which covered the forest glade and the snow-flakes which besprinkled me and the great Elder. You can imagine the state I was in!

“How do you feel now?” Father Seraphim asked me.

“Extraordinarily well,” I said.

“But in what way? How exactly do you feel well?”

I answered: “I feel such calmness and peace in my soul that no words can express it.”

“This, your Godliness,” said Father Seraphim, “is that peace of which the Lord said to His disciples: My peace I give unto you; not as the world gives, give I unto you (Jn. 14:21). If you were of the world, the world would love its own; but because I have chosen you out of the world, therefore the world hates you (Jn. 15:19). But be of good cheer; I have overcome the world (Jn. 16:33). And to those people whom this world hates but who are chosen by the Lord, the Lord gives that peace which you now feel within you, the peace which, in the words of the Apostle, passes all understanding (Phil. 4:7). The Apostle describes it in this way, because it is impossible to express in words the spiritual well-being which it produces in those into whose hearts the Lord God has infused it. Christ the Saviour calls it a peace which comes from His own generosity and is not of this world, for no temporary earthly prosperity can give it to the human heart; it is granted from on high by the Lord God Himself, and that is why it is called the peace of God. What else do you feel?” Father Seraphim asked me.

“An extraordinary sweetness,” I replied.

And he continued: “This is that sweetness of which it is said in Holy Scripture: They will be inebriated with the fatness of Thy house; and Thou shalt make them drink of the torrent of Thy delight (Ps. 35:8) [16]. And now this sweetness is flooding our hearts and coursing through our veins with unutterable delight. From this sweetness our hearts melt as it were, and both of us are filled with such happiness as tongue cannot tell. What else do you feel?”

“An extraordinary joy in all my heart.”

And Father Seraphim continued: “When the Spirit of God comes down to man and overshadows him with the fullness of His inspiration [17], then the human soul overflows with unspeakable joy, for the Spirit of God fills with joy whatever He touches. This is that joy of which the Lord speaks in His Gospel: A woman when she is in travail has sorrow, because her hour is come; but when she is delivered of the child, she remembers no more the anguish, for joy that a man is born into the world. In the world you will be sorrowful [18]; but when I see you again, your heart shall rejoice, and your joy no one will take from you (Jn. 16:21-22). Yet however comforting may be this joy which you now feel in your heart, it is nothing in comparison with that of which the Lord Himself by the mouth of His Apostle said that that joy eye has not seen, nor ear heard, nor has it entered into the heart of man what God has prepared for them that love Him (I Cor. 2:9). Foretastes of that joy are given to us now, and if they fill our souls with such sweetness, well-being and happiness, what shall we say of that joy which has been prepared in heaven for those who weep here on earth? And you, my son, have wept enough in your life on earth; yet see with what joy the Lord consoles you even in this life! Now it is up to us, my son, to add labours to labours in order to go from strength to strength (Ps. 83:7), and to come to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ (Eph. 4:13), so that the words of the Lord may be fulfilled in us: But they that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall grow wings like eagles; and they shall run and not be weary (Is. 40:31); they will go from strength to strength, and the God of gods will appear to them in the Sion (Ps. 83:8) of realization and heavenly visions. Only then will our present joy (which now visits us little and briefly) appear in all its fullness, and no one will take it from us, for we shall be filled to overflowing with inexplicable heavenly delights. What else do you feel, your Godliness?”

I answered: “An extraordinary warmth.”

“How can you feel warmth, my son? Look, we are sitting in the forest. It is winter out-of-doors, and snow is underfoot. There is more than an inch of snow on us, and the snowflakes are still falling. What warmth can there be?”

Called Home

About six in the morning, January 2nd, 1833, Hieromonk Paul of the Sarov monastery, on his way to attend the early Liturgy, smelled smoke as he passed by the cell of St. Seraphim. As there was no response from his knock at the door—which was latched from the inside—he went outside and told some of the brethren who were passing by. The Novice Anikita was able to break the door from its hinges.

On entering the cell the monks found that some coarse linen was smoldering, probably as a result of a fallen candle. St. Seraphim was found kneeling before the Virgin Mary icon, wearing his usual white smock, bare headed, with the brass crucifix his mother had given him hanging from his neck, and with his arms crossed.

The monks prepared St. Seraphim for burial according to monastic regulations, placed him in the oak coffin he had made, placed an enameled icon of St. Sergius with him according to his request, and carried him into the Cathedral where it remained for eight days and nights until all had had time to bid him farewell.

The news of his death spread quickly, and thousands of people gathered from the surrounding provinces. On the day of his burial there was such a throng of people in the Cathedral that the candles melted from the heat. St. Seraphim was buried on the south side of the sanctuary of the Cathedral, beside the grave of the recluse Mark who died fifteen years before him.

![]()