AD72, and Anacrites has ducked a fact-gathering mission for Vespasian, and sends Falco … whom he promptly betrays to a camel driver (Falco’s pseudonym for a nabataean chief minister) before he departs. Ah, this enmity between Anacrites and Falco. Will it ever end?

The scene is Petra, Nabataea, an independent kingdom and trade centre which somewhat liberally taxes goods en route and so attractive to Roma as a trading partner and future annexure to the Empire. Falco and Helena Justina are on a fact gathering mission for Vespasian. Falco has other reasons – he is on the lookout for a missing water organist, one Sophrona. He’ll be paid if he finds his quarry.

Falco and Helena Justina take a reverential curiosity visit to an eyrie height, the sacrifice temple of the god Dushara. The God Dushara, interestingly is the god of wine and fertility in the kingdom based on the city of Petra, now in Jordan. The festival of his birth was on 25 December and his mother, Chaabu, was said to be a virgin when he was born.

Nonetheless, Falco and Helena Justina stumble upon a watery murder finding a body face down in a rock pool. Falco is never one to let murder lie, be it in Rome, or elsewhere. Visiting a flea on the rump of civilisation does not change his values. Without a second thought, he arranges for the safety of Helena Justina, and turns down the path to pursue the perpetrator.

The Ancient Carny, the travelling troupe

Helena Justina and Falco are subsequently expelled from Petra and acquire a young priest by name of Musa as interpreter/watcher. They accept him into their tent. On the way out of Petra, they encounter a travelling troupe of actors. Helena Justina remarks on Falco’s poetry and odes and obtains a position for him as playwright, replacing the deceased Heliodorus (whom they found murdered on the mountain-top sanctuary of Dushara).

The travelling troupe-carny has many members, the manager, the actors, stage hands, extras, poster writers, and costume makers. It is an itinerant life of no fixed income, yet a life containing some satisfaction for those who participate, albeit for different periods of time. It is a life of dreams, broken dreams, future dreams, and the dreams they create for their audiences. Chremes, the manager, is a shrewd judge of cities and their populace and which plays will go down well. Falco learns quickly that the carny has a stock set of plays (most of which are known by heart by the actors) which are adapted to local audiences.

Falco’s retainer in Rome, Thalia, is a carny of another kind, with constrictors draped around her neck and provides a performance dancing with snakes. A baby elephant is being taught to walk a tightrope, when Falco arrives at the circus to visit Thalia.

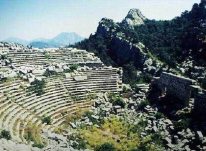

Dreams aside, the travelling troupe encounter indifferent magistrates in the Decapolis, and have varied luck in presenting their plays in the local theatre. There is tolerance, collaboration on stage props, sewing of costumes and variations to scripts. Falco edits his stock set of scripts and attends rehearsals. Somewhere in the recesses of Falco’s mind, his play The Spook Who Spoke takes shape and lines. Helena Justina proves a dab hand at marking up scripts while Falco is looking for a murderer among the troupe’s entourage.

A deceased playwright

Central to the narrative is the deceased Heliodorus, Falco’s predecessor, and the responses he effected upon the whole company. The troupe leader, Chremes shares with Falco that Heliodorus bullied the actors and terrorised the lower classes. In various iterations with the cast and extra hands, Falco builds up the personality of his predecessor. Heliodorus was a gambler, a cheat, a rapist, a thief, a bully, a tease, a taunt, and manipulated power over the troupe leader Chremes, and over the acting cast via his scripts. Falco’s search for the killer of Heliodorus lays a fascinating human pastiche of carny life. The playwright somewhat held all the strings with his stylus as he determined the roles, on stage presence and delivery of drama in the play as a whole. Success or failure to a large extent rested on the former playwright’s shoulders.

The travelling troupe was a big group with its failed actors, would be Thespians who were working as stage hands, and the extras, ticket sellers, promotional artists, etc. Thrown together by necessity, lives are treated with disdain and scorn, almost units of human work, where role, task and function were somewhat depersonalised. Tensions seethed close beneath the surface as Chremes provide somewhat dysfunctional leadership, resulting in almost mutiny at the nether end of the tour through the Decapolis. Personal relationships within the troupe were tense, tolerance was a sine-qua-non, as well as co-operation. The handsome actor Philocrates was universally despised for his refusal to help anyone in difficulty.

Humour, a line, a joke, a clown

Central to Falco’s investigations were the ‘twins’, the company clowns. Another troupe member is drowned, an attempt is made to drown Musa, Falco is dangerously drawn into participating in one clown’s repertoire in town on one occasion, and perhaps the scorpion who bit Helena Justina was not entirely in their tent by accident.

Central to the task of any performer is the synergy they build up with their audience. Phrygia was universally cited as excellent in one play; Grumio fascinates the crowds with his jokes libelling and denigrating citizens from other towns, and the other twin, Tranio, plays at life, plays with life, plays with other people’s lives. Gambling and gambling debts produce further tension and powerlessness.

What is the source of humour? What makes for the best jokes? How does a performer discern, touch and take control of that palpable energy of crowd, wherein that exchange takes place and people are drawn in to affinity with the performer? For some, it is inherent, internal, second nature. For others, it is external, learned or copied from ancient papyrus scrolls with jokes on them. A Greek, a Roman and an elephant all went into a brothel. When they came out, only the elephant was smiling. Why?

Therein lies the rub, the nexus of entertainment, capturing the human mind with wonder, dreams, synergy, thrills, daring and would-be realities. For that exchange of energy, participants part with their denarii, and the troupe earns their keep.

Imago Roma

Roman Amphitheatre

Available on Amazon

![]()