Two weeks in October, AD72 …

Falco has just returned from Palmyra; Petro is expelling Balbinus Pius (a master criminal) from Rome. Falco tags along at Petro’s request to witness the expulsion. Afterwards, Petro will aid Falco in transporting Geminus’s glass shipment to the Emporium, the landing place sea freight.

As the expulsion of Balbinus Pius is being witnessed, Rome is beset by a daring heist at the Emporium (a long secure shed on the Tiber to house sea freight delivered upriver from Ostia), and other daring heists occur. It seems another master criminal has stepped into the vacancy created by the expulsion of Balbinus Pius.

Fresh from Spain, Aelianus, the eldest son of Camillus Verus attends Helena Justina’s birthday party (where Aelianus is wrathful at Falco lowering his family’s status) (a matter Falco despatches very quickly. Unfortunately, Falco’s present for his love was stolen along with his father’s glassware, so carefully selected by Helena Justina and imported by Falco on his return. It seems this novel is a tour of all the low spots and low lifes of Falco’s Rome. Crims, hoods, thieves, snatchers, long-arms, and the goings on at brothels.

Citizens Rights, Criminal Rights

Falco reflects on the rights and duties of freedmen in Rome (note that refers to men, not women. Women had little or no legal status in Ancient Rome, except where marriage and dowry were concerned).

I suppose it is a comfort to us all – we who carry the privilege of being full citizens of the Empire – to know that except in times of extreme political chaos when civilisation is dispensed with, we can do what we like yet remain untouchable.

It is, of course, a crime for any of us to profiteer while on foreign service; commit parricide; rape a vestal virgin; conspire to assassinate the Emperor; fornicate with another man’s slave; or let amphorae drop off our balconies so as to dent fellow citizens’ heads. For such evil deeds we can be prosecuted by any righteous free man who is prepared to pay a barrister. We can be invited before a praetor for an embarrassing discussion. If the praetor hates our face, or merely disbelieves our story, we can be sent to trial, and if the jury hates us too we can be convicted. For the worst crimes we can be sentenced to a short social meeting with the public strangler. But, freedom being an inalienable and perpetual state, we cannot be made to endure imprisonment. So while the public strangler is looking up a blank date in his calendar, we can wave him goodbye.

In the days of Sulla so many criminals were skipping punishment, and it was obviously so cheap to operate, that finally the law enshrined this neat dictum: no Roman citizen who was sentenced to the death penalty might be arrested, even after the verdict, until he had been given time to depart. It was my right; it was Petro’s right; and it was the right of the murderous Balbinus Pius to pack a few bags, assume a smug grin, and flee.

Thus reflects Falco on Rome and the rights of the citizen.

Lowlife and Crime in Falco’s Rome

We meet all sorts of low-lifes:

- Flaccida, wife of Balbinus Pius, said to be a hard woman. Has female slaves with black eyes;

- Nonnius Albius, allegedly a poorly court witness. Rent collector for Balbinus Pius, and leaner-on of others, particularly brothel-madams;

- The Miller, a thick-skinned bone crusher with not much by way of nous;

- Little Icarus, a fancy fly-boy with a blade of any kind, and interested in education of rent defaulters on behalf of Balbinus Pius;

- Lalage, nee Rillia Gratiana, the astonishingly pretty daughter of a snooty stationer, turned refined proprietor of Plato’s (a house where men may obtain their satisfaction);

- Tibullinus, a centurion of the Sixth Cohort, and possibly on the take;

- Arica, sidekick of Tibullinus and of little responsibility.

- The Very Important Patrician, an astonishingly well known Magistrate and wearer of the purple who inspects brothels in his official duties and during his time away from his official duties, in the company of his lictors.

What sort of petty criminals are documented in the novel? Well, let’s have a look …

- purse snatchers

- grabbers

- confidence tricksters and bluffers

- strangling muggers

- boot stealer’s

- dirty alley girls with thugs for minders

- robbers of drunks and schoolchildren

- mobs who held up ladies litters

- thieves who beat up slaves

- reachers, adept at leaning across shop counters to grab money or goods

- hijackers who held up delivery carts

- lechers who grab and fumble

- organised robbers who ransacked mansions while bleeding porters lay bound in corridors and householders hid under beds

- prostitutes who engage in baby snatching and seeking ransom

Of course, you could be forgiven for walking past a crime-in-progress. Falco recalls going to the aid of a slave being raped by a hoodlum, only to have the slave attempt to snatch his purse!

An unfriendly city

Falco is walking home, late at night, wearing out the leather in his boots, yet again:

The city felt unfriendly. A cart raced around a corner, causing walkers and pigeons sipping at fountains to scatter; it must be breaking the curfew, for dusk had only just fallen and there had hardly been time for it to have reached here legitimately from one of the city gates. People pushed and shoved with more disregard than ever for those in their path. Untethered dogs were everywhere, showing their fangs. Sinister figures slunk along in porticoes, some with sacks over their shoulders, some carrying sticks that could be either weapons or hooks for stealing from windows and balconies. Groups of uncouth slaves stood blocking the pavement while they gossiped, oblivious to free citizens wanting to pass.

An irresponsible girl backed out of an open doorway, laughing. She banged into me, bruising my forearm and making me grab for my money in case it was a theft attempt. I roared at her. She raised a threatening fist. A man on a donkey shoved me aside, panniers of garden weeds crushing me against a pillar that was hung dangerously with terracotta statuettes of goggle-eyed goddesses. A beggar stopped blowing a raucous set of double pipes just long enough to cackle with mirth as a white-and-red-painted Minerva cracked me across the nose with her hard little skirt. At least being pressed back so hard saved me from the bucket of slops that a householder then chose to fling out of a window from one of the apartments above.

Insanity was in Rome

We could be forgiven for coming to the conclusion that the seedy side of Rome got Falco down from time to time. Indeed, in his short conversation with Aelianus, Aelianus is asking why Falco does what he does:

‘Some dogged lone operator attempting to right society’s wrongs without praise or pay!’

‘Pure foolishness’, I agreed briefly.

‘Why do it?’

‘Oh, the hope of gain.’

‘Strength of character?’ The family irony had not entirely bypassed Aelianus.

‘You’ve found me out. I’m a soft touch for ethical actions.’

Truth is what we speak,

Right Conduct is what we practise,

Love is what we live,

Peace is what we give,

Non-violence is the fruit.

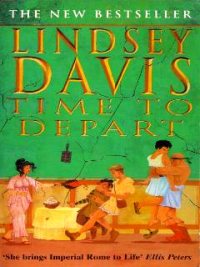

Available on Amazon

Imago Roma

Roman Brothel

![]()