Abraham Isaac Kook was an Orthodox rabbi, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine in the Land of Israel, the founder of Yeshiva Mercaz HaRav, a Jewish thinker, Posek, Kabbalist, and a renowned Talmid Chacham. He is considered one of the fathers of religious Zionism.

Abraham Isaac Kook was an Orthodox rabbi, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine in the Land of Israel, the founder of Yeshiva Mercaz HaRav, a Jewish thinker, Posek, Kabbalist, and a renowned Talmid Chacham. He is considered one of the fathers of religious Zionism.

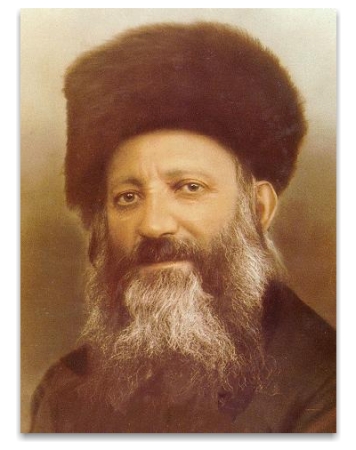

Abraham Isaac Kook, 1865 – 1935

Rabbinate of British Mandate Palestine

Europe

Abraham Isaac Kook was born to a deeply pious and learned Jewish family in 1865, in Grieve, Latvia, which was part of the then restricted world of the Jewish ghetto in Eastern Europe. He was a prolific writer, but he was also a man of action. In 1886 he married the daughter of R. Eliyahu David Rabinowitz-Teomim, rabbi of Ponevez. In 1888 he launched a monthly rabbinic journal, “Iturie Sofrim”. He served as rabbi in the Lithuanian towns of Zoimel (1888-1895) and Boisk (1895-1904) and as chief rabbi of Jaffa, Palestine (1904-1919). He was stranded by the First World War during a visit to Europe. In 1914 he went to Europe for Agudat Yisrael convention in Berlin. Caught by World War I, Rav Kook spent 2 years in St. Gallen, Switzerland. In 1916 he became rabbi of Machzikei HaDat congregation in London (1917-1918). In 1919 He returned to Israel, became rabbi of Jerusalem In 1921 He became Chief Rabbi of Israel, together with Sephardic Chief Rabbi Yaakov Meir. This was the most august rabbinic office in world Jewry, the chief rabbinate of Jerusalem, and of the whole Jewish community in Palestine. He served in this post during sixteen stormy years till his death in 1935.

Author

Rabbi Kook wrote voluminiously. His books include The Lights of Penitence, The Lights of Holiness, The Moral Principles, along with other letters, essays and poems. Rabbi Kook was not writing to defend Judaism against other religions, nor to eradicate threats and heresy. Rabbi Kook’s writings are almost wholly devoid of religious polemics. He was essentially an existentialist thinker to whom theological issues as such were of secondary importance. The essence of religion for him was in its existential implications, its concern to bring all life under the discipline of divine ideals. The test of religion at its highest was in the passion it inspires to bend life toward ethical and moral perfection.

The Lights of Penitence – Orot Hateshuvah – is Rabbi Kook’s most popular work. The first edition appeared in 1925 and there have been several editions. Only the first three chapters were written by Rabbi Kook, the remainder having been culled from his writings by his son, who edited the work.

The conventional view of penitence sees it as an effort to redress a particular transgression in the area of man’s relatoinship with God or to his fellow man. For Rabbi Kook, penitence is the surge of the soul for perfection, to rise above the limitations imposed by the finitude of existence. It is a reach for reunion with God from whom all creation has been separated by the descent to a particular incarnation of earthly existence. Penitence, in other words, is only one aspect of the drama of human life on its eternal return to the Divine, from whom it has descended.

Destitute?

On a Friday, the 28th day of Iyar, May 10, 1904, the Rav finally fulfilled his lifelong dream and made aliyah. He was greeted with much fervor and fanfare by his many followers. The Rav took a position as Rav of Jaffa. For a long time, the Rav did not seem to be bringing home any money. His Rebbetzin [wife] was having a hard time making ends meet and so she went to the directors of community service and complained that it had been so long since the Rav had received his salary. The directors became baffled by the Rebbetzin’s complaint, as he knew that the Rav had been paid on schedule, with no delay at all. After much investigation, it was discovered that the Rav had been giving away all his money to the poor. After that, the money was always given directly to the Rebbetzin.

On the 3rd of Elul 5679, August 29, 1919, Rav Kook became the Rav of Yerushalyim where he established his yeshiva, Merkaz HaRav. He also later instituted the Chief Rabbinate of Israel, which at the time consisted of himself and Rabbi Yaakov Meir Charlop.

As a halakhic authority charged with respsonsibility for rendering decisions that were to become the norm of law in the Jewish Community, Rav Kook revealed a flexibility that made him anathema to the zealots of the older type of traditionalism. Thus he sponsored a takkana that exemped Jewish agriculture from the restrictions of the sabbatical year. The zealots of the old order continue to ignore this takkana to this day, and are careful not to purchase from Jewish growers during periods their calculations tell them fall within the sabbatical year.

Each religion is a path

Rabbi Kook sought to rediscover how the Jewish peoples could serve the world. He did not expect that Judaism would supplant the religions of mankind. Rabbi Kook believed that the diversity of religion is a legitimate and a permanent expression of the human spirit, the the different religions are not meant to compete but to collaborate. “Conventional theology, he declared, assumes that the different religions must necessarily oppose each other …. But on reaching full maturiry the human spirit aspires to rise above every manner of conflict and opposition, and a person then recognizes all expression of the spiritual life as an organic whole”. “This does not erase the difference of levels between religions, between higher and lower, between the more holy and the less holy, and between the holy and the common. But each has its place in the life of the whole. Each is a path through which God is seeking to raise man to himself”.

The Inner Torah

Rabbi Kook’s published writings include four volumes in rabbinic law; a collection of poetry, a treatise on the mysticism of the Hebrew Alphabet, a treatise on penitence, a treatise on morals, two volumes of commentary on the Prayer Book, three volumes of correspondence and three volumes of reflections on God and man. Rabbi Kook’s teachings were more than a conceptual system rationally arrived at. He shows startling glimpses of transcendence and points of connections to the values contained in the major religions of humanity. He was a true mystic writing in the Talmudic manner and style, always in touch with the lights of the inner Torah, the inner divine presence. In one of his most revealing testimonials about himself, he declared:

“I love everybody. It is impossible for me not to love all people, all nations. With all the depth of my being, I desire to see them grow toward beauty, toward perfection. My love for the Jewish people is with more ardor, more depth. But my inner desire reaches out with a mighty love toward all. There is veritably no need for me to force this feeling of love. It flows directly from the holy depth of wisdom, from the divine soul. “It is no accident, but of the very essence of my being, that I find delight in the pursuit of the divine mysteries in unrestrained freedom. This is my primary purpose. All my other goals, the practical and the rational, are only peripheral to my real self. I must find my happiness within my inner self, unconcerned whether people agree with me, or by what is happening to my own career. The more I shall recognize my own identity, and the more I will permit my self to be original, and to stand on my own feet with an inner conviction which is based on knowledge, perception, feeling and song, the more will the light of God shine on me, and the more will my potentialities develop to serve as a blessing to myself and to the world. “The refinements to which I subject myself, my thoughts, my imagination, my morals, and my emotions, will also serve as general refinements for the whole world. A person must say, ‘The whole world was created for my sake”‘ (Arple Tobar, p. 22)

The Culture of the Jewish Peoples

“We began to say something of the immense inportance among ourselves but we have not finisehd it. We re inthe midst of our discourse, and we do not wish, an dwe are not able, to stop. We shall not abandon our distinctive way of life nor our universal aspirations. The truth is so right that we stammer; our speech is still in exile. In the course of time we shall be able to express what we seek with our total being. Only a people that hs completed what it started can leave the scene of history. To begin and not to finish – this is not in accordance with the pattern of existence.” (Essay on the Culture of Jewish People, 1909)

The Light of the Soul reflects the Light of the Divine

In Orot HaKodesh (2/303) Rabbi Kook wrote:

“The holy lights which burst forth at specific points in time and space, must be appraised at their true value, with the knowledge that they are secretly spread across all of existing space, that they travel through concealed passageways and secluded streams, until finally surfacing at one luminous spot.”

Creation is duality, a mixture of light and dark, maya and the One Reality, which is light, truth, Oneness. Yet, human beings are caught up in the world of real-seemingness, versimilitude. What is light, what is dark, what is Divine? What is holiness for man? Is there one holiness for all?

“The holiness of man, revealed through the Jewish nation, lies hidden within Everyman, within the whole of humanity, in the depths of inviolate chambers, and it continually flows through a hidden labyrinth, until finally coming to light through the glow of the Jewish soul.”

Rabbi Kook reveals the divine revelation through the prism of Judaism. All religions are paths to the one true reality; each has its own vision of the All, the holiness within and without all that exists in Creation (and thus reflecting the glory of the Creator) and delivers that reality. Culture shapes mind, text must speak to context; Rabbi Kook is the Chief Rabbi of a nation, and thus speaks to the Jewish soul. But that which he addresses is in every soul, hence the use of the term Everyman .

Rabbi Kook continues:

“The holiness of space fills the entire world, yet it remains hidden and invisible, and the secret waves of holiness push endlessly forth towards their destined revelation, until they find expression through the Land of Israel, the pinnacle of all the dust of the universe, and from there to the holy spot, the holy Temple, and the Rock of Foundation, ‘Out of Zion, the epitome of beauty, God has appeared.'”

The holiness of space is the utter divine reality of the Creator. Via negativa, there is no place wither Divinity is not. All of creation reflects the work of the Creator, be it in the garden of Eden, or the vast interstellar spaces. Creation has no void; it has only the Divine. Divine self-giving comes to all races and to all creatures; divine knowledge is placed within the minds and hearts of mankind, so it is the bounden duty of man to search, to know, to reveal the epitome of beauty, God only, only God.

Human life is Time. The Divine is Time. The Lord and Master of Time is that which creates, Time, the Divine. In the world of duality, Time is; in the world of non-duality, what we might call eternity, Time reveals the Divine through human activity:

“The holiness of time spreads across eternity, daily expressing benediction, and the rays of holy light are drawn along a secret path, until they are revealed at the holy times, through the holiness of Shabbat, which is the origin of all the holy times and emanates with holiness toward the entire world and toward Israel; and through the holiness of the holidays, which serve as receptacles of holy emanation; and through the Jewish people, who sanctify the holidays.”

The Soul is the spark of the Divine in the heart of every man, woman, child. The Soul animates the human body; the senses are instruments, organs of perception, which enable the human to recognise and adore the Creator:

“This is similar to the relationship of the soul to the senses, the seeing eye and hearing ear, whose light is not indigenous but rather stems from the light of life which floods the soul and grants life to the entire body, and which in turn gives man quality of life through the gifts of sight and of hearing; this burst of potential, when it reaches the point most ripe for its revelation, finds expression through sight and hearing.”

It is the nature of God to reveal who he is to Man. Knowledge of His existence has been placed in Man’s heart, and when man walks the paths of blessedness, everything in creation reflects the glory of the Creator. All energy, manifest as matter, is Divine Energy. All energy manifest is simply the energy of the soul in different forms. Thus, the Spark of the Divine, the Spark of Holiness, exists within all:

“Thus it is with all the various revelations in our world, throughout the annals of history, revelations both natural and supernatural; whatever is revealed at a designated time is but a concentrated expression of a multitude of forces which lay dormant, whose action was delayed until the appropriate hour had arrived. The only true change lies in the naming [of the spark of holiness], in public expression and revelation. The essence is not new, ‘since the creation, I (God) have existed.'”

Legacy

While Rabbi Kook is exalted as one of the most important thinkers in mainstream Religious Zionism, there are several prominent quotes in which Rav Kook is quite critical of the more modern-orthodox Religious Zionists (Mizrachi), whom he saw in some ways as naive and perhaps hypocritical in attempting to synthesize traditional Judaism with a modern and largely secular ideology. Rav Kook never shied away from gently offering constructive criticism to his peers, religious and secular. Rav Kook was interested in outreach and cooperation between different groups and types of Jews, and saw both the good and bad in each of them. His sympathy for them as fellow Jews and desire for Jewish unity should not be misinterpreted as any inherent endorsement of all their ideas. That said, Rav Kook’s willingness to engage in joint-projects (for instance, his participation in the Chief Rabbinate) with the secular Zionist leadership must be seen as differentiating him from many of his traditionalist peers. In terms of practical results, it would not be incorrect to characterize Kook as being a Zionist, if one defines a Zionist as one who believes in the re-establishment of the Jewish people as a nation in their ancestral homeland. Unlike other Zionist leaders, however, Kook’s motivations were purely based on Jewish law and Biblical prophecy.

The Israeli moshav Kfar Haroeh, a settlement founded in 1933, was named after Rav Kook, “Haroah” being a Hebrew acronym for “HaRav Avraham HaCohen”. His son Zvi Yehuda Kook, who was also his most prominent student, took over teaching duties at Mercaz HaRav after his death, and dedicated his life to disseminating his father’s writings. Many students of Rav Kook’s writings and philosophy eventually formed Hardal Religious Zionist movement which is today led by rabbis who studied under Rav Kook’s son at Mercaz HaRav.

In 1937, Yehuda Leib Maimon established Mossad Harav Kook, a religious research foundation and notable publishing house, based in Jerusalem. It is named after Rabbi Kook.

Thirsting for God

Expanses divine my soul craves.

Confine me not in cages,

Or substance or of spirit.

I am love-sick --

I thirst, I thirst for God,

as a deer for water brooks.

Alas, who can describe my pain,

Who will be a violin to express the songs of my grief,

I am bound to the world, All creatures, all people are my friends,

Many parts of my soul

Are intertwined with them, But how can I share with them my Light?

This page last updated 30 August 2019

This page first updated 10 May 2007

© Saieditor.com

![]()