Indigenous peoples, today, are arguably among the most disadvantaged and vulnerable groups of people in the world. The international community now recognises that special measures are required to protect their rights and maintain their distinct cultures and ways of life.

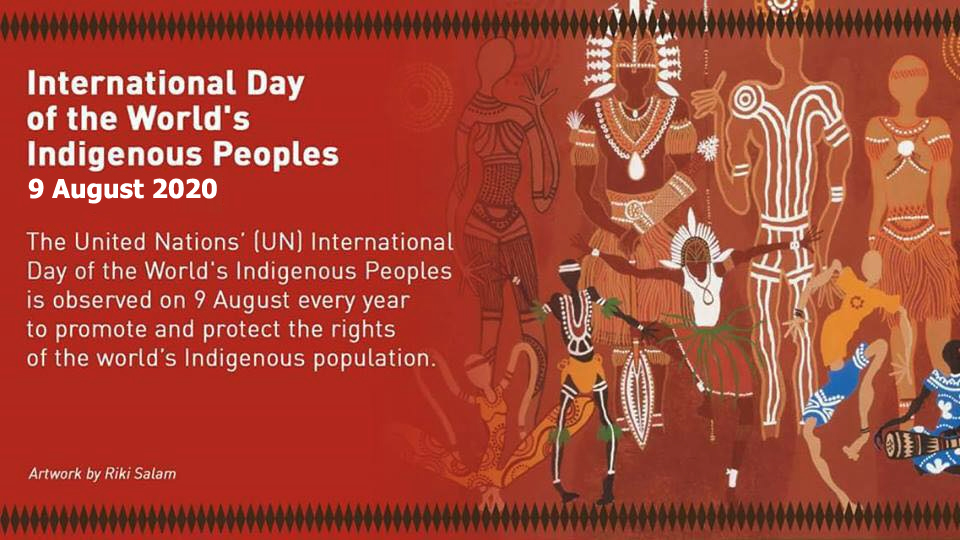

To raise awareness of the needs of these population groups, every 9 August commemorates the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, chosen in recognition of the first meeting of the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations held in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1982.

To look at the spiritual essence of human beings, all humans possess a soul, called the Atma. All peoples are illuminated within by the atma, for the intellect, the source of intelligence and mind, is nearest to the soul and gives over 80% illumination to the intelligence. Where society and culture mark a difference in human life, colour of skin does not make for any difference.

Indigenous Languages

- At present, 96 per cent of the world’s approximately 6,700 languages are spoken by only 3 per cent of the world’s population.

- Conservative estimates suggest that more than half of the world’s languages will become extinct by 2100. Other calculations predict that up to 95 per cent of the world’s languages may become extinct or seriously endangered by the end of this century.

- The vast majority of the languages that are under threat of disappearing are indigenous languages. It is assessed that one indigenous language dies every two weeks.

- This pressing threat has been described as the most critical issue faced by indigenous peoples today. Indigenous languages are critical markers of the cultural health of indigenous peoples. When indigenous languages are under threat, so too are indigenous peoples themselves.

- Indigenous languages are not the only methods of communication, but also extensive and complex systems of knowledge. Indigenous languages are central to the identity of indigenous peoples, the preservation of their cultures, worldviews and visions and an expression of self-determination.

- The threat of extinction of indigenous languages is generally seen as the direct result of colonialism and colonial practices that resulted in the decimation of indigenous peoples, their cultures and their languages. Through policies of assimilation, forced relocation, boarding schools and other colonial and post-colonial policies, laws and actions, indigenous languages in all regions face the threat of extinction.

- Globalization and the rise of a small number of culturally dominant languages have exacerbated the threat to indigenous languages.

Covid 19 and Indigenous Peoples

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic poses a grave health threat to Indigenous peoples around the world. Indigenous communities already experience poor access to healthcare, significantly higher rates of communicable and non-communicable diseases, lack of access to essential services, sanitation, and other key preventive measures, such as clean water, soap, disinfectant, etc. Likewise, most nearby local medical facilities, if and when there are any, are often under-equipped and under-staffed. Even when Indigenous peoples are able to access healthcare services, they can face stigma and discrimination. A key factor is to ensure these services and facilities are provided in indigenous languages, and as appropriate to the specific situation of Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples’ traditional lifestyles are a source of their resiliency, and can also pose a threat at this time in preventing the spread of the virus. For example, most indigenous communities regularly organise large traditional gatherings to mark special events e.g. harvests, coming of age ceremonies, etc. Some indigenous communities also live in multi-generational housing, which puts Indigenous peoples and their families, especially the Elders, at risk

As lockdowns continue in numerous countries, with no timeline in sight, Indigenous peoples who already face food insecurity, as a result of the loss of their traditional lands and territories, confront even graver challenges in access to food. With the loss of their traditional livelihoods, which are often land-based, many Indigenous peoples who work in traditional occupations and subsistence economies or in the informal sector will be adversely affected by the pandemic. The situation of indigenous women, who are often the main providers of food and nutrition to their families, is even graver.

Yet, Indigenous peoples are seeking their own solutions to this pandemic. They are taking action, and using traditional knowledge and practices such as voluntary isolation, and sealing off their territories, as well as preventive measures – in their own languages.

Religion and Indigenous Peoples

Religion or belief is often defined as a particular collection of ideas and/or practices that:

- relate to the nature and place of humanity in the universe and, where applicable, the relation of humanity to things supernatural;

- encourage or require adherents to observe particular standards or codes of conduct or, where applicable, to participate in specific practices having supernatural significance;

- are held by an identifiable group regardless of how loosely knit and varying in belief and practice;

- are seen by adherents as constituting a religion or system of belief.

Freedom of religion is enshrined within the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Article 12 states:

Indigenous peoples have the right to manifest, practice, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; and the right to the repatriation of their human remains. States shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned.

The right to freedom of religion and belief is also enshrined under the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. According to Article 18:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his [sic] religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or in private, to manifest his [sic] religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Spirituality is a broader term than religion, understood as more diffuse and less institutionalised than religion. The term spiritual pertains to the incorporeal, the non-material, the ethereal, the seat of moral or religious nature, to the ecclesiastical and the sacred. It refers to an experiential encounter and relationship with otherness, with powers, forces and beings beyond the scope of the material world. The other might be God, nature, land, sea or some other person or being.

It is worthwhile reflecting about key concerns of Indigenous spirituality, in particular:

- traditional Indigenous spirituality

- the impact of Christian missions, Islam and government policy on traditional Indigenous spirituality

- how Indigenous spirituality and religion has evolved into new forms

- issues pertaining to freedom of religion and spirituality in different nations today.

The above imputes no judgement on any religion that has conducted evangelisation of indigenous peoples. We note that history is often written from the point of view of the winner. The underside of history is the narrative of the losers. There is a narrative of those who have been evangelised, often compromised by loss of history and culture and suppression of religious and spiritual practices.

![]()