Pope John XXIII – Angelo Roncalli – was born in a very poor family of 13 children in Northern Italy. He was priest, bishop, diplomat and Pope. A conservative in doctrine, during his life he frequently reached out to those of other faiths – sometimes called schismatic – and even, the Church would call some perfidious infidels. Not John XXIII, who was horrified by Shoah, and took every step he could to save lives of Jews. Here, we look to his career and actions as Interfaith Mentor.

Pope John XXIII – Angelo Roncalli – was born in a very poor family of 13 children in Northern Italy. He was priest, bishop, diplomat and Pope. A conservative in doctrine, during his life he frequently reached out to those of other faiths – sometimes called schismatic – and even, the Church would call some perfidious infidels. Not John XXIII, who was horrified by Shoah, and took every step he could to save lives of Jews. Here, we look to his career and actions as Interfaith Mentor.

If all men are a reflection of God, how can I not love them all, how can I despise them, how can I not have respect for them? This thought must prevent me from offending my brothers in any way; I must remember that all are the image of God, and that perhaps their souls are more beautiful and dearer to the Lord than mine.

These reflections seem to have guided him during his life as a pastor and diplomat. They are the foundations of a theology of religions. But Roncalli was not a theorist of dialogue. It was through his actions and his attitudes that he opened up paths of dialogue, of which we will give some significant examples. Let us specify beforehand that, although he met with Jews and Muslims, it was above all in non-Catholic Christians that Roncalli invested himself, which cannot be called interreligious dialogue. But at a time when ecumenical dialogue did not exist, there was not much difference in the discourse when speaking of so-called schismatic or heretical Christians and other non-Christian religions — except when it came to the Jews, who were the object of a very singular teaching. The former were seriously in error since they had left the true path, while the latter were in error through ignorance. Thus, to take the step of entering into dialogue with the Orthodox or Protestants was almost the same as entering into dialogue with Jews or Muslims: one must cross a line of demarcation. This is what John XXIII did.

In 1925, Archbishop Roncalli was sent to Bulgaria as a visitor, then as an apostolic delegate, even though the pope had not had a representative in that country for seven centuries. He stayed there for ten years. Immersed in a new cultural world, predominantly Orthodox, he arrived in a situation of extreme conflict between the Vatican and the Orthodox Church, coupled with tension between Latin and Eastern Rite Catholics. Roncalli had a method that he would not abandon during his life and would often repeat: to leave aside what divides and to concentrate instead on the search for what unites in love and prayer. He established contacts with the Orthodox, which was not always appreciated by Rome; exercised charity without distinction of religion during the earthquake of 1928; and mediated the marriage of the Orthodox tsar Boris III with the Italian Catholic princess Jeanne de Savoie. On December 31, 1934, he said goodbye to this country where he had lived in poverty:

If someone from Bulgaria passes by my house — whether at night or during a difficult period in his life — he will always find a candle burning in my window. Let him knock on the door. No one will ask him if he is Catholic or Orthodox — the fact that he is a Bulgarian brother will suffice.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Archbishop Roncalli was sent as apostolic delegate for Turkey and Greece, where Orthodox hostility towards Rome was no less great than in Sofia. He lived in Istanbul, in a predominantly Muslim environment, and had to be in contact with the new Republic of Turkey, with other religious communities, and with the Orthodox. The Catholics, who were in a very small minority after the upheavals at the end of the Ottoman Empire, were very withdrawn, which was not to the liking of Bishop Roncalli, who wrote to them,

We are here a modest minority who live on the surface of a vast world with which we have only superficial relations. We like to distinguish ourselves from those who do not profess our faith: Orthodox brothers, Protestants, Israelites, Muslims, believers and non-believers of other religions . . . . It seems logical that each one should look after himself, his family and national tradition, keeping tightly within the limited circle of his own coterie . . . My dear brothers and sons, I must tell you that, in the light of the Gospel and of Catholic principle, this is a false logic.

Responding to Shoah

Roncalli was animated by an extraordinary love for Istanbul and for the Turkish people, whose language he learned. He was the architect of the first thaw with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which manifested itself in 1939 with the presence of Orthodox representatives at the funeral ceremony of Pius XI. Then he went to the historical district of Fanar, seat of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, where he was received with all honours by Patriarch Benjamin. This was the first time this had happened in centuries. His dealings with the Jews were of a different nature, since they were guided by the urgency of saving lives. From 1940, since Turkey was neutral, Archbishop Roncalli used his influence, his ability to create links, and his old relations, such as with Tsar Boris III, to save the maximum number of Jews from death. The Shoah made such a strong impression on him that as soon as he became pope, during the Good Friday ceremony in 1959, John XXIII interrupted the ceremony so that he could repeat the oration for the Jews, deleting the traditional mention of perfidis. In October 1960 he greeted a group of American Jews with the words, “I am Joseph, your brother” (Joseph was his baptismal name). He was thus evoking the reunion between the Jewish people and the Church to which he aspired.

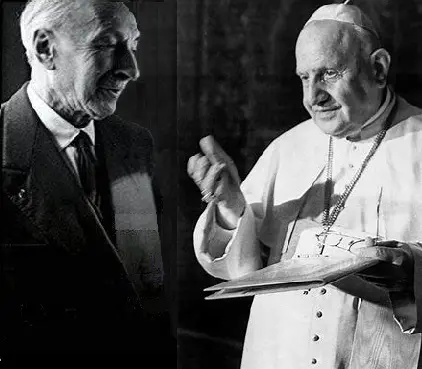

But it was his meeting with the French Jew Jules Isaac that was decisive in giving concrete expression to his desire for a response from the Church to Auschwitz. This renowned historian, who had been deposed by the Vichy regime, had lost his wife and daughter in the Shoah and was co-founder of the Jewish-Christian Friendship. He was received in audience by John XXIII on June 13, 1960, and presented him with an argument for reforming Christian teaching on the Jews. The meeting lasted twenty minutes. Jules Isaac was won over by the successor of Peter, whom he described as “a round fellow, rather fat, with a face of strong and rustic features — a big nose — very smiling, willingly laughing, with a clear look, a little malicious but where there is an obvious goodness which inspires confidence.” For his part, John XXIII never ceased to show understanding and sympathy for his visitor, and when Jules Isaac, before retiring, asked if he could take away some hope, the pontiff replied: “You are entitled to more than hope.” This was the beginning of the long journey of the conciliar text Nostra Aetate, which in its Chapter 4 put an end to the teaching of contempt for the Jews and their collective condemnation for the death of Christ.

John XXIII was seventy-seven years old when elected pope. A man of the field, rich in varied experience, including twenty years of life in the East as a minority, he was attentive to history and the signs of the times. He believed that the Church should declare peace to the world and enter into dialogue with it. He announced the convocation of an Ecumenical Council a few months after his accession to the chair of Peter, giving the floor to bishops from all over the world and inviting representatives of other confessions to participate partially in the work of the Second Vatican Council. John XXIII wanted Christians to enter into a movement, whose name in Italian has been preserved as aggiornamento (update, modernisation, adaptation, renewal): this will have an impact in many areas, among others, in the relationship to other religions. Of this Council, of which he would only see the first session, he would say

“It is not the Gospel that has changed, it is we who understand it better.”

Conclusion

When asked why the Council was convened, John XXIII would have opened his office window wide and replied, “To let fresh air into the Church.” Others have heard him say, “I want to open the window of the Church so that we can see what is happening outside and the world can see what is happening inside.” Whether these anecdotes are entirely accurate or not, they seem to sum up what Pope John XXIII leaves us as a teaching for interreligious dialogue. Opening a window not only brings air from outside and renews the room but also allows one to see beyond the walls of one’s home. This is basically what Pope John XIII did during his long pastoral and diplomatic career.

![]()